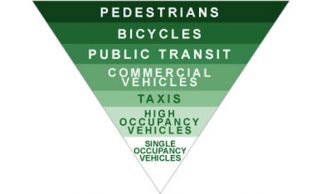

Saying that “not everybody can cycle,” Commissioner Amanda Fritz Tuesday urged the city to switch the order of its “green transportation hierarchy” to prioritize public transit above biking.

“Everybody can use the bus,” Fritz, who a city staffer mentioned was supported by written testimony from advocacy group Elders in Action, said at a council work session on the city’s new comprehensive plan. “And our transit system is not good.”

Fritz’s comments drew disagreement from her counterpart Steve Novick, who said the city’s plan already calls for big upgrades to transit and that “historically we’ve spent a hell of a lot more on things other than biking and walking.”

the city’s Climate Action Plan.

“The strategy is about the system working together as a whole, and I feel strongly that the best way for that to happen is to design the streets for walking and biking,” Novick said. “The streets will be better for pedestrians and people on bicycles when they’re getting to transit.”

Novick also argued that it’s not true that a vast number of people can ride buses but are unable to bike.

“In places like the Netherlands and Denmark that have made it truly safe to ride bicycles, people of all ages ride bicycles,” Novick said.

You can view their exchange below starting at the 51 minute mark, or click here to jump straight to it on YouTube.com.

Planning Commissioner Chris Smith, who sits on the board of Portland Streetcar and has been deeply involved in both biking and transit advocacy for years, also attended Tuesday’s work session to defend the existing hierarchy.

“Absolutely people need to have transit as a choice,” he said. “Amsterdam and Copenhagen can only have a 40 to 50 percent bicycle mode share because they also have a 30 percent transit mode share.”

But though he said he very much supports more money for transit, there are various ways biking should be a generally higher priority.

“For the distance that can be covered, it’s probably the least expensive form of mobility,” Smith said. “A transit trip costs us up to several dollars; bicycle trips cost the government pennies.”

Smith noted that the city’s transportation plans are built around the assumption that 25 percent of trips will happen by bike in 15 years and 25 percent on transit.

“If it’s 30 percent transit and 20 percent bike, it’ll probably still be a great city, but it’ll cost us a lot more to operate it,” Smith said.

Advertisement

In practice, the city rarely faces direct tradeoffs between biking and transit. A more detailed version of its policy is that transit should be the most desirable mode for trips of three miles or more; biking, for trips of one to three miles; and walking, for trips of up to one mile.

But Smith said the city’s transportation hierarchy would prevent the city from making errors like the one he said it committed when it added a streetcar line on the central eastside’s MLK/Grand couplet without adding bike lanes.

“That is still a black hole for cyclists,” Smith said. “We would not be able to do that in the future under this policy.”

The debate also comes at a crucial time for regional spending. The Metro Council is right now weighing competing pressure from TriMet, freight advocates and the Bicycle Transportation Alliance over whether to send flexible federal dollars to high-capacity bus or rail lines on Southwest Barbur and Powell-Division; to freight access projects; or to biking and walking improvements around schools.

“The deck is stacked in favor of transit right now,” Smith said. “Transit has a multi-billion dollar federal program that this region and this city has shown great enthusiasm for providing local match for. We have the occasional TIGER grant for cycling that’s a couple orders of magnitude smaller than the federal trough for transit. And transit enjoys a regional tax base and an agency that spends that tax base. We have none of those advantages for cycling.”

(Chart: “Federal and state capital transportation investments in the Porltand region, 1995-2010” – Metro)

Fritz replied that much of that federal money for transit goes to capital projects in the central city, which is of little use to many Portlanders, and that even in the central city, frequent bus service ends after 9 p.m.

She mentioned that she’d recently driven on North Williams Avenue for the first time since it was restriped to add a left-side buffered bike lane and remove an auto passing lane. In the future, she said, she will drive on “side streets” rather than ever driving on Williams again during rush hour.

“There are places and times that people cannot and will not cycle,” she said. “When I got off work at OHSU at 11:30 at night on a weekend night or any other night, I was not going to get on a bike and ride seven miles uphill to get home. I would probably never have gotten home.”

Correction 10:20 p.m.: An earlier version of this post quoted Fritz as saying she will from now on drive on side streets rather than on Williams. She said she will do so from now on during rush hour.

— Michael Andersen, (503) 333-7824 – michael@bikeportland.org

BikePortland can’t survive without paid subscribers. Please sign up today.