(Photo: Diane Yee)

As we mentioned in this week’s news roundup, Seattle’s 16-month-old bike sharing system is in a very tight spot.

With the Pronto system taking in only 68 percent of the money required to meet its operating costs last year and the city considering taking it over in order to bail it out, many Portlanders are rightly wondering whether the upcoming Biketown system (which will be operated by the same company, Motivate) could face similar problems.

We talked to some of the country’s leading independent bike-share experts today to get their take. Here’s what we heard.

Seattle’s #1 problem is low ridership per bike

(Via JournalistsResource.org)

(Via JournalistsResource.org)

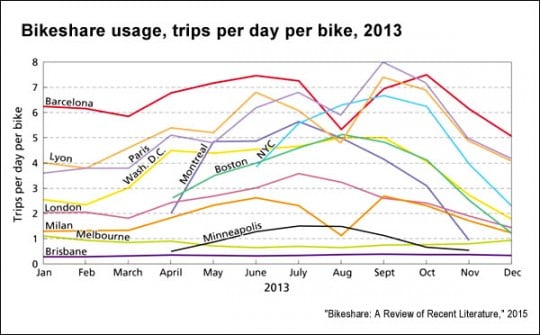

This is maybe the single most important number for all vehicle-sharing systems.

“You get your really high-performing systems like New York or Chicago that have like five trips per day,” said Phil Goff, a Boston-based senior associate for Alta Planning + Design who specializes in bike sharing feasibility studies. “And then there are some pretty high performing systems in the 2 to 3 range like Salt Lake City or Boston.”

Seattle averaged only 0.8 rides per bike in its first year.

“It sounds like the ridership projections were off, which happens,” said Paul DeMaio, a bike sharing consultant with Virginia-based Metrobike LLC. “If revenues are off, as it sounds like they were, then obviously it impacts the sustainability of the business.”

If Seattle had anticipated ridership that low, it wouldn’t necessarily be a problem.

“It’s not microscopically low,” said Goff. “There are other cities that are roughly within the one trip per day per bike range.” He mentioned Chattanooga, Tennessee, and Columbus, Ohio.

But Seattle, where biking in general is certainly more popular than in Chattanooga or Columbus (as well as Salt Lake City, Boston, New York and Chicago, for that matter), did anticipate higher ridership. Which is why…

Pronto launched with a bunch of loans

This is the first major difference between Seattle’s system and Portland’s. Alaska Airlines put up a lead sponsorship worth $1,000 per bike per year for 2014 through 2019 — $2.5 million total — but that and the city’s public start-up funds didn’t turn out to be enough to launch the system.

So the nonprofit that manages Pronto, Puget Sound Bike Share, took out loans to cover the difference. Last year, debt payments added up to almost $300,000, 15 percent of the system’s operating costs. Next year they’re on track to hit $500,000, according to a presentation being prepared for Seattle’s city council meeting Tuesday.

Biketown is starting from a much healthier place. Portland’s $10 million title sponsorship from Nike is four times the value of Seattle’s sponsorship — $2,000 per bike per year after accounting for the fact that Portland will launch with 1,000 bikes rather than Seattle’s 500.

Moreover, Biketown’s up-front costs per bike will be lower than Seattle’s because its “smart bike” system (which puts the computer on the bike rather than in the kiosk) saves a lot of money on station purchasing and installation.

Seattle has three major ridership challenges compared to other U.S. systems

(Image: Google Street View)

Here they are, probably in descending order of importance:

1) Huge hills in the middle of the service area

2) A system with two hubs instead of one

3) A mandatory helmet law

Portland faces none of these challenges.

Our inclines (for example, the climbs to Portland State University or the Mississippi District) aren’t nothing, but they’re not much compared to First Hill or Capitol Hill. Knowing this, Pronto launched with seven gears on its bikes instead of the usual three. I don’t know about you, but that’s definitely not enough to get me pedaling up Yesler on a 50-pound bike.

Another Seattle issue: the decision to put 11 of its 54 stations in the University of Washington area. A study last year concluded that station density per square mile is essential to maximizing bike share ridership. Seattle’s system spread itself thinly over five square miles rather than concentrating on a single area.

Advertisement

Spreading itself thinly is certainly a risk for Portland; it first planned an eight-square-mile service area for 600 bikes (thinner than Seattle, that is) and now plans a somewhat larger service area for 1,000 bikes. But unlike Seattle, Portland isn’t likely to have two distant hubs; instead, it’ll probably concentrate stations in the downtown and gradually get less dense further out.

The last item is the most interesting, so let’s devote a whole subhed to it.

Helmet laws probably hurt bike sharing

Seattle, which was home to an influential 1989 study of bike helmets that has never been replicated and was repudiated by the federal government in 2013, is one of the few cities in the world where helmets are required for all adult bike users.

Though Seattle’s helmet law isn’t heavily enforced, it’s had several effects. First, it’s obligated cash-strapped Pronto to spend about $80,000 a year offering helmets to its users. Second, it makes people who choose to rent a helmet (for $2 a pop) go through the time-consuming step of finding a properly sized one and adjusting its straps properly. Third, it propagates the idea that bike sharing (which has yet to be associated with a single fatality anywhere in the United States and actually tends to reduce biking injuries in cities where it operates) is dangerous.

Aside from Seattle (and Vancouver BC, which doesn’t yet have a bike share system but is expecting to launch one) the main home of adult bike-helmet laws is Australia. And, lo and behold, that country’s two bike-sharing systems also perform woefully, with half the per-bike ridership of Pronto.

Because of all these differences between Portland and Seattle, Goff (who certainly has a financial interest in bike sharing’s success, but not in Pronto in particular) said it doesn’t make sense to assume Biketown will have problems just because Pronto is.

“I hope there aren’t people in Portland saying, well, it’s not working so well in Seattle, it might not work down here,” he said.

There might be a silver lining in Seattle’s cloud

(Photo: Seattle DOT)

We’ve been rough in this post on Seattle, which is also a city doing a lot of things right. So let’s close on a contrarian note: despite the costs, this might actually turn out to be terrific for Seattle.

Here’s the basic problem with North American bike sharing: Almost all cities have been holding it to some of the standards of public transit — pushing for it to be used by people of all incomes and races, for example — but not giving it the public subsidies that virtually every U.S. public transit system would collapse without.

It’s entirely appropriate to hold a public system to a high standard. But equity goals cost money. And if Seattle’s city council votes tomorrow to subsidize Pronto by buying it out and then follows up with the massive expansion it’s already proposed, that could put Seattle on track to become the first U.S. city that actually uses public money to create a truly great bike share system.

That’s DeMaio’s interesting take.

“Some folks look at it as a takeover, as I think I’ve heard,” the Virginia-based consultant said. “However, this is very similar to what happened in many cities around the country, including in New York, with the private sector starting up subway lines and the lines not being profitable. So in the end the public sector stepped in, combined the lines, made them easier to use, expanded the service and brought back the customers.”

Could that happen? Should it? As always, we’ll be watching.

— Michael Andersen, (503) 333-7824 – michael@bikeportland.org

BikePortland can’t survive without paid subscribers. Please sign up today.