(Charts: BikePortland. Data here.)

In the days since President Obama signed the new five-year FAST Act into law, we’ve been talking to several local experts about how it might affect Oregon.

Is this a win? Well, it depends on what you’re starting from.

The simplest answer, according to experts at the state DOT and the regional planning agency Metro, is that it’ll continue the status quo.

That’s in contrast to the previous bill passed in 2012, known as MAP-21, which was “pretty chock-full of policy changes,” according to Trevor Sleeman, the Oregon Department of Transportation’s federal affairs specialist.

“MAP-21 was a pretty policy intensive bill and in comparison, you’re right, the FAST Act is relatively light,” Sleeman said last Thursday in response to a question about the general outlines of the bill, which Sleeman was still in the process of reading. “It’s probably more of a funding-focused bill, generally speaking.”

Metro’s Ted Leybold offered a similar summary.

That’s fair enough; getting any sort of action out of today’s ideologically entrenched Congress is an accomplishment on some level, and that’s what happened over the last month. But if it’s just a funding bill, let’s look at the funding.

Advertisement

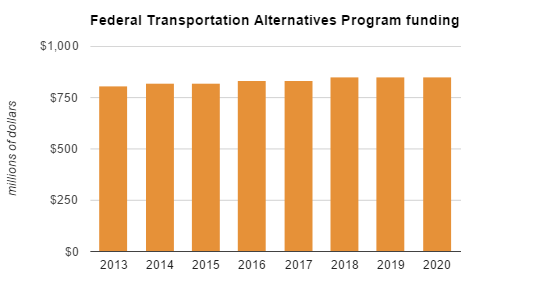

The bike-related number that’s been kicked around most often in the last two weeks is the funding for the Transportation Alternatives Program, a pot of money, mostly from federal gas taxes, created by MAP-21 to pay for things like:

on- and off-road pedestrian and bicycle facilities, infrastructure projects for improving non-driver access to public transportation and enhanced mobility, community improvement activities, and environmental mitigation; recreational trail projects; safe routes to school projects; and projects for planning, designing, or constructing boulevards and other roadways largely in the right-of-way of former divided highways.

That’s not everything the federal government spends on bike infrastructure, but it’s one of the biggest chunks. In a post on Dec. 2 about the transportation bill, the low-car advocacy group Transportation for America described it as “one of the few programs where funding doesn’t grow with the overall increases in bill.”

Here’s the TAP funding agreement that’s been described by some as a victory, rising from $820 million this year to $835 million next year and $850 million from 2018 through 2020:

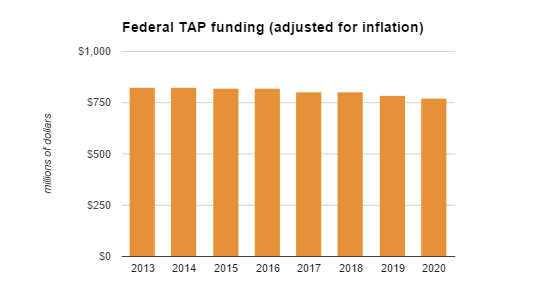

Now, let’s look at it after adjusting for inflation. (This is just inflation from the general consumer price index, not for actual construction projects — if infrastructure costs rise faster than consumer prices, the value of $850 million will decline faster, and vice versa.) This chart is in 2015 dollars. Inflation for future years assumes the Federal Reserve’s target rate of 2 percent; this is the level they’ll be trying to keep inflation at when they probably raise interest rates this month.

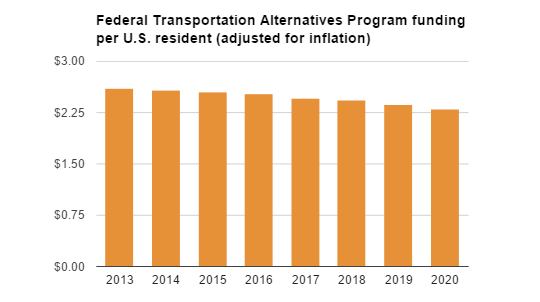

And here’s what the chart looks like after adjusting for inflation and population (this is the same chart as the top of the post):

And does the increase in TAP funding even keep up with the growth in the number of bike riders in America? Not exactly, says Caron Whitaker, the VP of government relations for the League of American Bicyclists:

.@BikePortland @BikeLeague increase in $ for bikes doesn't keep up with demand, its incremental improvement #bikechat

— Caron Whitaker (@CaronWhitaker) December 11, 2015

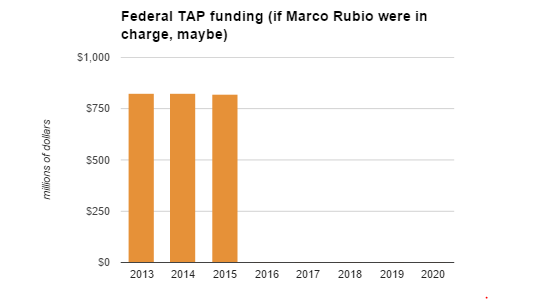

Is this a win? Well, it depends on what you’re starting from. Eleven months ago, an oil-industry-funded coalition of advocacy groups was sending a shot across Congress’s bow by declaring that “Washington continues to spend federal dollars on projects that have nothing to do with roads like bike paths and transit.”

This perspective is captured by the transportation policy of, for example, presidential candidate Marco Rubio, who says he wants to cut federal gas taxes by 80 percent and “free states from the strings that come attached to federal funding,” presumably including programs such as this one. So if that view had prevailed in Congress this year, these charts might look like this:

If that happened, would ODOT keep spending meaningful amounts of money on bike-specific improvements? Probably somewhat. Another virtue of the new bill is that it lets states and regions spend money on bike infrastructure if they want to, even if it’s not marked specifically for bike infrastructure.

How many other DOTs would do so? How much?

As with all legislative sausage-making, it’s hard to say what might have happened.

Tim Blumenthal, president of biking advocacy group PeopleForBikes, said Tuesday that with the bill, the country has “turned the corner” on the debate over whether bike infrastructure and programs deserve federal funding.

“It provides five years of steady funding for bike projects with the type of long-term certainty that we haven’t had since 2004,” he said.

— Learn more about the FAST Act in this summary prepared by Toole Design Group.

(Disclosure: PeopleForBikes is my other half-time employer, but I rarely interact with the team that lobbied on this bill and didn’t follow their work. This is written as third-party journalism and isn’t informed by my PeopleForBikes work.)

— Michael Andersen, (503) 333-7824 – michael@bikeportland.org