This is the second in a three-part series. Read the first installment here.

This is the second in a three-part series. Read the first installment here.

For most of Portland’s history, the land we know today as the Lloyd District was best known for failure.

Holladay Park: named for a scoundrel who planted its trees and then gambled away his fortune. The state and federal buildings along Lloyd Boulevard: advance outposts of a government center that never arrived. And Lloyd himself: an oil multimillionaire who died all but cursing the city he’d fallen in love with 40 years before.

For people who ride bikes in Portland, the legacy of those years — rolled out in acres of asphalt, traced like permanent detours onto the city’s bike maps — eventually became an insider’s joke told with a slight sneer.

“Avoid the Lloyd,” the famous homemade stickers of the mid-2000s said. “Trust an original. Go to Beaverton.”

But how did the Lloyd District become a suburb hidden in the middle of a city? And what happened as the 20th century ended that has started to open it back up — putting it on course to become what could be, 10 or 15 years from now, the most bike-oriented high-rise neighborhood in the country?

The answers to those questions tell a story about Portland, and a story about all American cities.

They also suggest a lesson that Portland, like all American cities, is still struggling to learn about itself.

The undivided subdivision

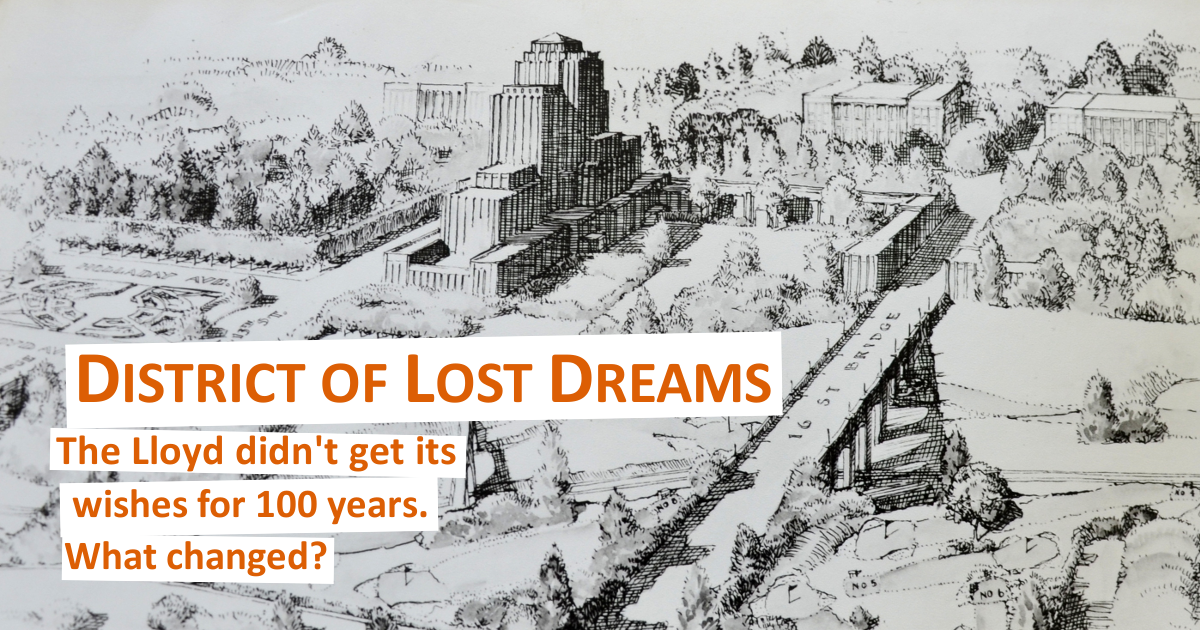

Before the land just north of Sullivan’s Gulch was named for Ralph Lloyd, it was named for someone else: Ben Holladay.

Born in 1819, Holladay left his parents’ Kentucky home for a road trip in his late teens and never came back. He hit it big before his 30th birthday with a business shipping supplies to U.S. troops in the Mexican-American War. In 1862, he bought the stations of the failing Pony Express and reinvented it as a profitable stagecoach line.

Then he moved to Portland and it all fell apart.

Railroads were transforming the country in the 1860s, so Holladay switched his business from horse carriages to steam engines. But when he started trying to develop the acres he’d bought along the gulch, the rail magnate made a fateful decision: for some reason, unlike most of Portland’s early property owners, he didn’t build a streetcar line to his land.

“He never extended any kind of transit service to this property,” said Steve Dotterrer, a Portland historian and the city’s former top planner. “There was one on Broadway, but even that was pretty late. … So as a residential subdivision, it didn’t fill up.”

Railroads turned out to be bad news for Holladay all around. He bought too many too fast and was ruined in the Panic of 1873. He died 15 years later, leaving the city a long series of bribes and brothels, and also a mostly vacant tract of land that everyone called “Holladay’s Addition” for the next 50 years.

Then someone else showed up.

The country and the city

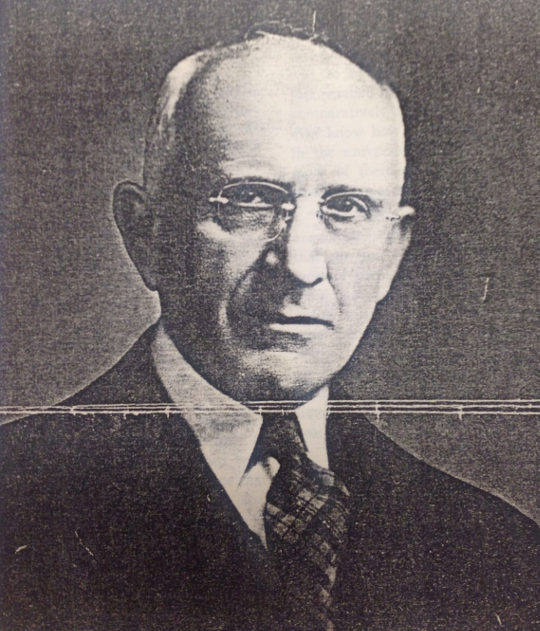

Ralph Lloyd came from a family of Welsh ranchers. But he wanted to be a singer.

Born outside Los Angeles in 1875, Lloyd worked his way into college in San Francisco in the 1890s. He studied geology but tried making a living on his voice in the city. Lloyd stuck with it until a letter arrived from his father, saying he was needed on the ranch. At age 21, he moved back home.

He helped run the ranch for nine years. Then one day in 1905 Lloyd told his parents he was quitting to take a job at a wood-pipe factory.

His mother was baffled, but it turned out that Lloyd’s new boss was grooming him for management. Lloyd and his wife moved to Olympia, Wash., in 1907, to investigate an unprofitable factory and successfully turned it around. The next year, he was promoted to senior vice president and relocated to Portland.

The Lloyds fell head over heels for their new town.

Lloyd, 33, was convinced he had discovered the next Los Angeles. Like many people of the time, the rancher’s son thought of cities essentially as leeches that lived off the wealth of a countryside — so the lusher the countryside, the fatter the leech.

“You have an enormous hinterland from which to draw, which is bound to make this the outstanding city of the Pacific Northwest,” Lloyd wrote later.

Lloyd started pooling his savings to buy buildings in Kenton and inner Northeast. But the treasure he wanted most was the huge, weirdly undeveloped acreage known as Holladay’s Addition.

“Nowhere else on the coast can one find such a body of vacant property in the heart of the city,” Lloyd would write. “This property is bound to be valuable in the immediate future.”

Dreams deferred

No one else seemed to agree. Portland’s money had always been on the west side, people said, and that’s where it would stay.

The young pipe executive found a wealthier business partner and made an offer on the land, but the deal fell through. Three years later, his mother died and he moved back to Los Angeles to take over the ranch.

Then, in 1912, he struck oil.

The Lloyd family, it turned out, had been running cattle on the seventh-largest oilfield in California. Ralph Lloyd was 37 when the first well on his land exploded with pressure from the vast reserves beneath it. All of which made it especially convenient that, as a young man home from geology school in 1903, he’d convinced his father not to sell the mineral rights to their land.

Within a few years, Lloyd was a millionaire. And he knew exactly where he wanted to spend it.

In 1926, he bought Holladay’s Addition and 170 surrounding parcels for $1.65 million, the equivalent of $22 million today. Working from his Los Angeles office, Lloyd made plans and mailed political contributions to Portland city council members.

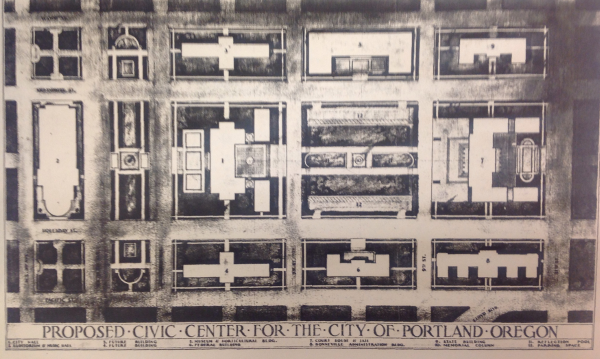

Holladay’s Addition, he decided, was destined to become Portland’s “second downtown,” a mix of apartments, shops and government office buildings in the geographic center of the city.

No bank would open a branch on the east side. Lloyd started one himself so he could borrow from it. Portland’s 200-foot blocks, the shortest in the United States, weren’t suited to the grandeur he wanted, so he decided to merge the ones on his land into “superblocks,” 440 feet on each side.

‘A strange Moloch from Los Angeles’

Lloyd had fallen in love with the city in 1911, the peak of Portland’s streetcar age. But the 1920s were the age of the automobile, and Lloyd set about making sure his district embraced it.

In April 1929, he wanted to widen the street that ran alongside the gulch to fit more traffic, but the city didn’t have money to spend. So Lloyd bought the adjacent houses himself, knocked them down and donated the land to the city. The city council named it Lloyd Boulevard.

It didn’t make him popular. “Shrubs of a few years growth were featured as helpless victims to be sacrificed before the golden altar of a strange Moloch from Los Angeles,” a local newspaper wrote of the project.

Nine adjacent property owners sued Lloyd and the city, saying he had no right to build public roads with private money. A judge agreed. Lloyd was confused.

“In Los Angeles we beg people to spend their money,” he wrote to a friend. “In Portland they enjoin them to keep them from spending it.”

Another letter, marveling at Portland’s decision not to knock down buildings to add lanes to West Burnside: “I cannot understand why the people of Portland offer so much resistance to improvements that in the long run will be so beneficial to them. It seems to me that the people of the west side in opposing the widening of West Burnside are simply committing suicide as far as their properties are concerned.”

Advertisement

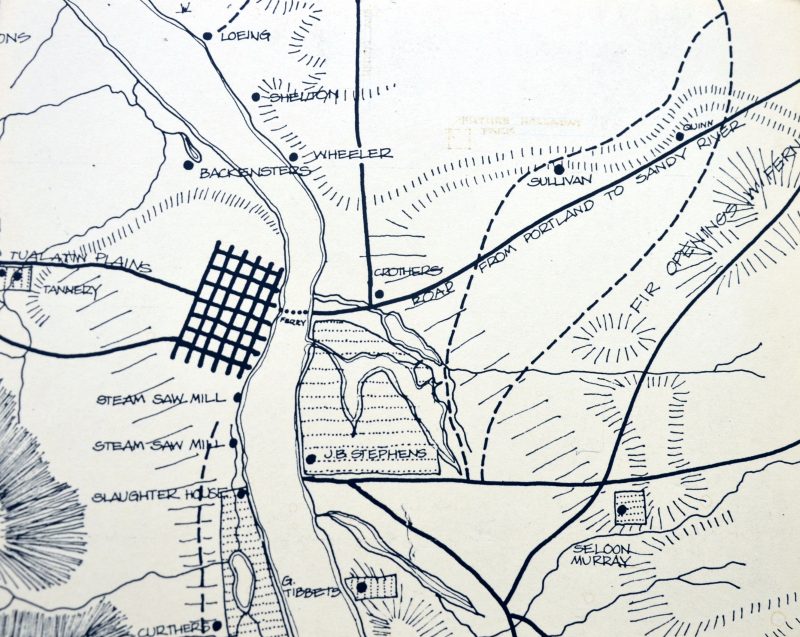

A forgotten city

Lloyd broke ground on the centerpiece of his $40 million plan, a 24-story hotel just east of Holladay Park, in August 1929.

Two months later, the stock market crashed. Lloyd’s own money was in oil, but everyone else in the city stopped building. His plan collapsed.

Grass grew in the pit that was supposed to become his hotel. Musicians started using it as an informal concert venue during the summer.

Lloyd kept buying houses in the area for 20 years, still looking for his big chance. At one point, in 1937, he announced that his goal for the development was to serve the “middle class rather than the rich.” But other than a few state and federal buildings, his district never rose. No one wanted to build a second downtown between his boulevards. He died in 1953.

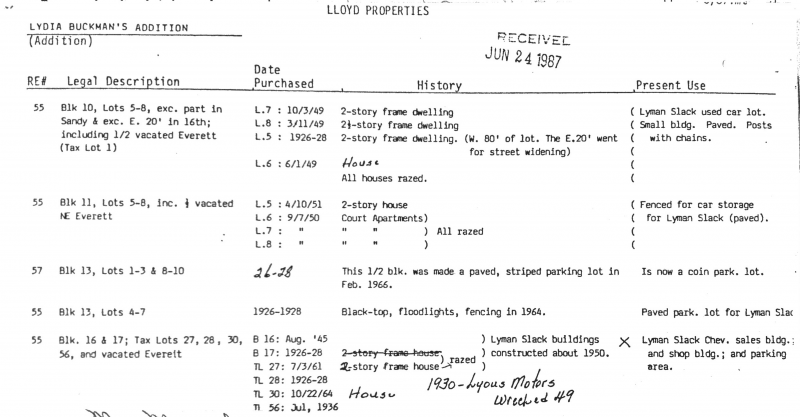

A stray purchase record from his company’s files shows the fates of a few of the houses he bought.

The district’s fortunes improved after Lloyd died.

His three daughters and their families finally finished developing a hotel; it opened in 1959. Across the street, they hired an architect of the Space Needle to design one of the country’s largest shopping malls, ringed with three stories of free multi-level parking garages to ensure a stream of customers.

They gradually found office tenants, too. The huge, undeveloped expanses of Lloyd’s district turned out to be perfect for what the employers of the 1960s and 1970s needed badly: parking lots to store the cars of college-educated workers from the newly built suburbs. Finally, a few towers started to rise.

“Lloyd office space going like hotcakes,” a 1979 Daily Journal of Commerce headline announced.

For a while, Lloyd’s notion of what a good city was — a pipe through which private cars and the harvests of the countryside could flow quickly — seemed to have arrived.

But cracks were appearing, too. An undated Willamette Week article stored in the Ernie Bonner Papers at Portland State University (which are the main source for this history) mostly praised the district’s success, but added:

The ubiquitous automobile, the lifeblood of any shopping center office building complex, dominates most human activity in the area. It even threatens the atmosphere of the center itself. For despite the construction of certain community amenities and facilities, they are separated by roads and acres of parking lots, creating a non-walkable, inhuman environment — a marked divergence from Ralph B. Lloyd’s original dream.

Death and life

By 1989, the Lloyd was considered a problem spot.

People were regularly getting mugged while walking through Holladay Park from MAX stop to mall. Local janitors kept discovering toilets clogged by drug needles. The huge parking garages, uninhibited for so much of the day, had become crime magnets; that year the district reported more than 700 car prowls, about two per day.

Office space in the Lloyd couldn’t command the premium it once had. The landowners got uneasy.

In 1995, Pacificorp, the utility that had bought most of the land from Lloyd’s children, got an offer from a 38-year-old man from Connecticut named Hank Ashforth. His company wanted to buy 17 blocks of the Lloyd District.

“What we saw from the East Coast was fixed-rail transit bisecting the district,” Ashforth recalled in an interview this month. “We understood the power of what we now call transportation-oriented development. … We own an office building right at the Greenwich railroad station, and it’s been unbelievably productive.”

Ashforth saw something else, too: the big lots of Holladay’s Addition, still mostly undeveloped.

A new direction

Rick Gustafson, a former Metro president and development consultant who has lived just north of the Lloyd for 35 years, said Hank Ashforth’s purchase set the district on a new course.

“He had pushed for his family, the Ashforth family, to modify their business model,” Gustafson said. “They buy office buildings; that’s what they have done historically, for three generations. Hank was pitching housing: residential development and mixed use.”

Gustafson said Ashforth met “enormous resistance” from his board of directors, largely his family members, when he pitched the idea of adding residential towers to a crime-ridden inner-city office park in the least interesting metropolis on the West Coast.

But Ashforth and his executive vice president, a former Pacificorp property manager in his early 30s named Matt Klein, won their argument. It was Klein, Ashforth said, who hit on the formula that would give the district the life it had never had.

Klein decided that the Lloyd District needed to start charging for auto parking, and use the proceeds to encourage transit, biking and walking instead.

Even today, the plan would probably sound outlandish to most Portlanders. How could that possibly be good for business? In 1995, Gustafson said with a laugh, it sounded even stranger.

“Maybe he was just young enough that new ideas could appeal to him, as opposed to the formulas that developers often get themselves into,” Gustafson said.

Under Klein’s guidance, the district created a transportation management association to start orchestrating the transition. (Klein left Portland in 1999 for a job with a major real estate firm in Washington, D.C. He is now its president.)

The lessons of history

(Photo © J. Maus/BikePortland)

Twenty years later, more than 100 years after a young Ralph Lloyd walked down a street that didn’t yet carry his name and imagined it as the greatest neighborhood in the Northwest, something is definitely happening.

In 2011, a different southern California company — this one called American Assets Trust — signed a deal with Ashforth to develop its properties.

Two years ago, their management company persuaded the city to remove two auto lanes from NE Multnomah Street, one of the roads Lloyd had widened, to add protected bike lanes and on-street metered parking. The main reason, executive Wade Lange explained at the time, was that people don’t tend to spend money on streets designed for speeding cars.

The mall that Lloyd’s children built is still the biggest one in Portland, but malls are on the wane across the country. After Nordstrom’s began to signal that it was pulling out, the mall’s owners sold to a Texas-based company, Cypress Equities. It’s announced plans to redevelop part of Holladay Park, remodel the parking garage to create a direct street entrance for the first time, and open a row of street-facing shops along Multnomah.

The concert pit that was once supposed to hold Lloyd’s hotel became a movie theater’s parking lot in 1987. Last month, a developer announced that he’d acquired an option to redevelop it as a 980-unit apartment-retail complex.

Earlier this month, American Assets Trust entered design review for the second of three planned redevelopment projects that will slice Lloyd’s superblocks back into 200-foot squares, reconnecting the old grid with pedestrianized streets and on-site bike valets.

Bike infrastructure, though improving, is still on the drawing board. We’ll discuss it in Part III of this series.

Many Portlanders are dubious of the district’s rapid changes. Some say the new buildings will clog streets with cars. Some say they’ll benefit only the rich. Some warn that if the Lloyd has taught Portland anything, it’s that big plans can collapse.

That’s true. And today’s might, too.

But the other enduring lesson of the Lloyd District is about more than the Lloyd District. It’s about what a city is and isn’t.

A city is not a leech. A city is not a pipe. A city is not a plan.

A city is a place.

Coming in two weeks: The bikeways it’d take to make the Lloyd great.

*This article was possible largely thanks to a biographical manuscript about Ralph Lloyd and other documents in the Ernie Bonner Papers at the PSU Library Special Collections.

— This in-depth series is brought to you by the bike-loving folks at Hassalo on Eighth, the Lloyd District development that is now leasing. We agreed on the subject of the series but they have no control or right to review the content before publication. Learn more about our sponsored content here and read all the articles in the series here.