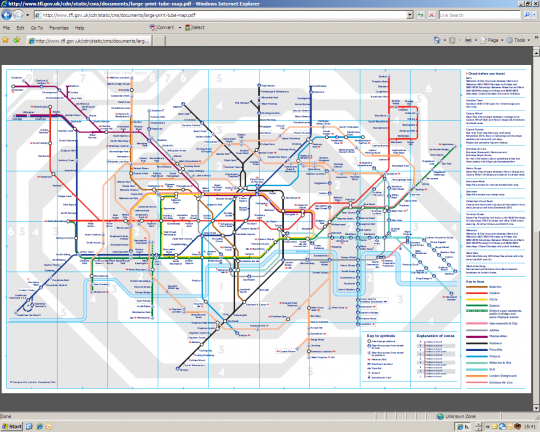

(Image: Transport for London)

London is making it happen.

“It dwarfs any equivalent program, certainly in the UK, probably anywhere in Western Europe.”

— Ben Plowden on London’s new $1.4 billion biking program

The last time he visited Portland, in 2003, Ben Plowden was several years into a job as the first full-time director of Living Streets, a small walking advocacy group. The city he worked in, London, had recently created a new regional government.

When Plowden returned to Portland last week, it was as the London regional government’s top surface transportation official – and he was here to explain how and why the region has just approved a $1.4 billion investment in biking over the next decade.

If spent as planned, Plowden said it’ll be one of the biggest municipal investments in cycling in the history of the world.

“It dwarfs any equivalent program, certainly in the UK, probably anywhere in Western Europe,” Plowden said of the $130 million annual budget, which will be divided among 1/3 education and enforcement programs and 2/3 infrastructure.

So something is working in London. But what? Last week we visited two events by Plowden, whose trip to Portland was sponsored by the public transport nonprofit Transit Center, to find out. Here’s what we learned London has.

1) An anti-congestion charge.

(Photo: Mark Ames)

Since 2003, driving a car into central London between 7 a.m. and 6 p.m. has cost $18 per day. The proceeds go into the regional transportation budget.

How was this approved? The key, Plowden explained, was support from freight customers.

“The reason that the congestion charge went in in 2002-2003 was that business knew how much congestion was causing them,” Plowden said. “It took a whole lot of discretionary car use off the network overnight.”

Here in Portland, there’s deep awareness among businesses of the job-killing costs of auto congestion. The problem, as we reported last month, is that the Port of Portland and some other freight customers believe that increasing auto capacity is the only viable way to reduce congestion; in a region where toll roads are almost unheard-of, they see an anti-congestion charge like London’s as impossible.

I asked Plowden whether toll roads were common in London before its anti-congestion charge began. They weren’t, he said.

2) A politician who rides.

The most important person behind London’s biking improvement is the one at the top: London’s center-right Mayor Boris Johnson.

“It’s difficult to exaggerate how important Boris being a commuter cyclist is,” said Plowden. “He carries his stuff in a rucksack on his back. and he’s done it basically his entire working life. … Like the mayors of Copenhagen in the 1970s, that’s a really important part of of making cycling what it is.”

After two terms, Johnson is returning to Parliament next year with his eye on becoming prime minister. Plowden said his departure will be “a sad day indeed” but called it “unlikely” that the next mayor will do anything worse for biking investments than to slow them down somewhat.

“This is actually quite an important part of the political landscape of London now,” he said.

(What about Portland? Well, as we shared last spring, no member of our current City Council spends much time on a bicycle.)

3) A very strong regional mayor system.

(M.Andersen/BikePortland)

Johnson’s commute habits wouldn’t matter much if he, like his predecessor Ken Livingstone, weren’t in control of almost every lever of power in the region.

“Ken Livingstone said if I’m elected, we’re going to have a congestion charge, and within two years we had one,” Plowden said. “Boris Johnson said if I’m elected, we’re going to become the world’s greatest cycling city. And we’re now spending a billion pounds on that objective.”

Advertisement

The “lesson of the London story,” Transit Center Executive Director David Bragdon said Friday, is “unity.”

“These are the results of really good governance structures and clear accountability for who’s doing what,” said Bragdon, a former president of Portland’s Metro regional government. “Americans, we’re very much in these jurisdictional boxes. These structures, they constrict us.”

Bragdon argued that the problems of concentrating power among a few people are outweighed by the advantages of the public knowing who to blame for its problems.

4) An organization built to see the big picture.

One effect of London’s integrated governments is that it put the same agency in charge of both arterial roadways and public transit.

In Portland, the Oregon Department of Transportation wouldn’t save much money if people driving on Powell switched to buses, or if people riding buses switched to bikes. But because Transport for London runs the whole transportation system, it saves money when the whole system gets more efficient.

Transit and bikes are efficient. Transport for London noticed – and started investing heavily in making them better.

In terms of vehicle road space, Plowden said, “buses are way way way more efffieient than anything else. Cycling is second. … If we have a finite amount of space and amount of money and people are going to be moving around the city, what’s the most efficient way of doing that? You have to start making the hard economic arguments.”

But if Transport for London hadn’t been able to see the whole picture, those arguments might have fallen on deaf ears.

5) Urgency.

(Photo: Nicolas Chinardet)

For all that, Plowden said, London might have accomplished little if not for two coincidences that created a sense that the city had no time to spare.

Starting in 2004, the year it won a bid to host the 2012 Olympics, London was on a deadline. If it didn’t have a massively functional system for car-free transport by that summer, it would be swamped by traffic.

“We set an objective that nobody except an elite athlete would arrive at any Olympic event with a car,” Plowden said.

In the run-up to 2012, London launched a bike share system, improved three rail lines, started running a new high-speed rail and built a cable car across the Thames.

Then, in late 2013, a series of six biking fatalities over two weeks seized the public’s attention around the need for biking improvements. Plowden called this a key catalyst for London’s massive investment to come.

6) Great ideas from other cities.

(Photo: Bike Texas)

Plowden didn’t mention this at all last week. But one of the most important things about London’s accomplishments is that every single one of them had already worked elsewhere.

Amsterdam, just across the English Channel, has billions of dollars worth of the world’s best bike infrastructure. Modern bike sharing came from Paris; the anti-congestion charge, from Singapore. Seville, Spain, had seen biking soar from 0.5 percent in 2007 to 7 percent biking in 2012 by rapidly building a connected 80-mile network of protected bike lanes; biking advocates across Europe are now looking to it a model.

One of the best things happening in the world right now is that it keeps getting easier for ideas to spread from one country to another. London’s huge victory in the last few years stems from Londoners like Plowden who decided to start stealing neat ideas from Paris, Amsterdam and (yes) Portland, Oregon.

How do good ideas spread? One way is when smart people carry them across the ocean to talk about them.

See you again in 2027, Ben. Meanwhile, we’ve got some work to do.