It was this March that Brian Sysfail, a regular user of Clinton Street, decided that if nothing else was going to get in the way of through-traffic on the Clinton Street neighborhood greenway, he was.

“Don’t like the increase in traffic on Clinton during rush hour and especially drivers cutting through neighborhoods?” he asked in a Facebook invitation to 278 people. “Neither do a lot of cyclists and pedestrians. So how about we all ride bikes together as a group after work on Friday.”

“This is a peaceful action to raise awareness that Clinton is not a short cut for drivers in rush hour,” he added.

Occasional activism like Sysfail’s is just part of a rising tide of complaints about Clinton Street, which has become a spillover for car traffic avoiding construction on Division or heading to its new apartment buildings and restaurant row.

Clinton bikeway is no fun anymore thanks to Division St folks trying to run us over in order to get in line at Pok Pok @BikePortland #wtf?

— Brooke Ann S. (@pdxgirlfriday) July 26, 2014

“I’m terrified of SE Clinton anywhere west of 39th but especially between 12th & 21st where it’s a total speedway,” wrote Kari Schlosshauer, Pacific Northwest Regional Policy Manager for the Safe Routes to School National Partnership, in an essay on BikePortland last month. “We ought to implement more of those creative and interesting diverters that let bikes and people through, but make cars go back to the arterials — this helps make our neighborhoods places for people.”

The talk of traffic problems on Clinton puts an important question to Portland’s street designers: how much traffic can a neighborhood greenway handle?

Greg Raisman, the Portland Bureau of Transportation’s traffic safety specialist and a co-creator of the neighborhood greenway concept, said in an interview that there is no question that Clinton’s auto traffic levels are at or above the traditional maximum for neighborhood greenways: 3,000 motor vehicles per day.

“Above 3,000, we put in bike lanes, generally,” Raisman said.

On March 31, two weeks after Sysfail’s ride, the city measured auto traffic at 25th and Clinton. The count was 3,028.

When are diverters necessary?

The National Association of City Transportation Officials’ street design guide, a document developed from the work of innovators like Raisman, says this about “bicycle boulevards,” a class that includes Portland’s more multimodal neighborhood greenways:

“Bicycle boulevards should be designed for motor vehicle volumes under 1,500 vehicles per day (vpd), with up to 3,000 vpd allowed in limited sections of a bicycle boulevard corridor.”

To keep motor traffic volumes at or below that target, NACTO says cities should install occasional traffic diverters to block through auto traffic while allowing bike traffic to cross.

Advertisement

Raisman agrees that streets like Clinton (and Lincoln, a few blocks north of Division, where he said traffic counts are now around 2,500) would be better for biking and walking with another traffic diverter or two.

But he doesn’t think the diverters, which typically cost $20,000 to $100,000 to install including planning and outreach to the neighborhood, are a huge benefit to safety on greenways.

“Our safety performance over time has been excellent,” he said. “70 percent of our streets are residential. Less than 20 percent of bike and pedestrian crash activity happens there. … There’s comfort factors that are important in how many cars are on the road. But from a pure safety perspective, the big threat is where you’re crossing the busy streets.”

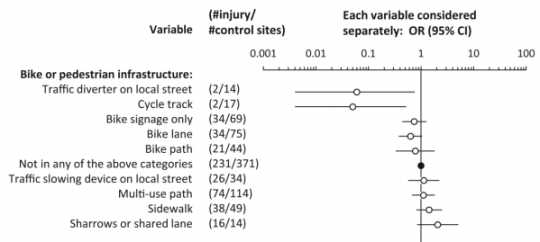

An academic study of injury rates in Vancouver BC, and Toronto, published last year, seems to differ slightly with Raisman’s take. Here’s its chart of the risk associated with different types of infrastructure, with the less dangerous marked to the left and the more dangerous marked to the right:

“Traffic diversion from local streets has the lowest odds ratio, whereas traffic slowing devices (small traffic circles and speed humps) show one of the higher odds ratios,” study co-author Kay Teschke, of the University of British Columbia, wrote in an email.

In a related study, local streets marked as bike routes in Vancouver and Toronto actually showed more injuries per user than local streets not marked as bike routes.

Teschke theorizes that without diverters, the same things that make greenways attractive for biking — direct connections and few stop signs — make it attractive for driving, even with traffic calming.

How to make things better

Raisman said he’s familiar with Teschke’s work but doesn’t think it holds up in Portland because the same data shows that small traffic circles, common in Vancouver, are a particularly risky way to slow traffic.

“When they’re improving traffic calming, they’re using traffic circles,” Raisman said. “We don’t really do that — we use speed bumps.”

Even so, Raisman didn’t question that traffic diversion on Clinton could improve the street. The bigger obstacle is finding the $20,000 to $100,000 that it costs to install a diverter.

“Right now, while we’ve had advocacy to improve a place like Clinton, we don’t have the funding,” Raisman said. “Even if we had the political will to do something, we don’t have the resources to do something right now. And I think Clinton will be a difficult conversation. … It’s a very dense section of the city where a lot of people live, where you have businesses right on the route.”

Asked for advice to people like Sysfail, Schlosshauer and others who want to make the case for diverters on Clinton or other streets, Raisman said they should “get involved in a neighborhood” to start building local support for the change.

“The life of a city is a long, complex thing,” he said. “Eventually, once we have funding available, I’m sure we’ll have the conversation.”