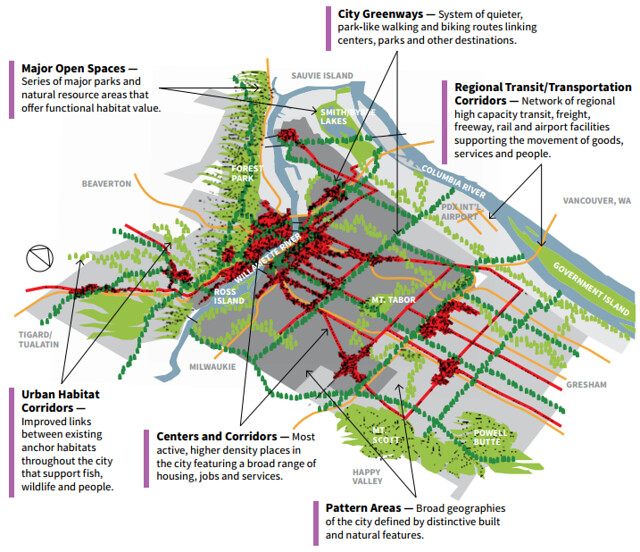

In case you weren’t sure whether Portland is truly unusual as mid-sized U.S. cities go, the 20-year comprehensive plan map released this week ought to make it clear.

The plan might be the city’s clearest statement ever that it’s betting everything — not just the future of biking or riding mass transit, but everything — on being able to make car-lite transportation dramatically more attractive than it is now.

“To get the most out of the infrastructure we’ve got, you’ve got to get people into other modes. That’s part of preserving the capacity for people who need it.”

— Joe Zehnder, Chief Planner, City of Portland

Because the city calculates that 122,000 new households will arrive in Portland by 2030 — that’s 50 percent more than it has today — it needs to increase the capacity of its streets. But instead of doing this by knocking down buildings for turn lanes, onramps and parking garages, almost everything on the city’s transportation agenda (with the notable exception of truck and rail freight improvements) would contribute to reducing the amount of space the average person takes up while they’re moving around.

“People who are driving today and want to keep driving, more power to them, and they can still do that,” city transportation spokesman Dylan Rivera said Wednesday. “But we have to acknowledge that growth is still coming and we have to figure out how to accommodate that.”

Joe Zehnder, the city’s chief planner, agreed: it’s not just walking, biking and riding transit that depends on these improvements. If Portland doesn’t make car-lite transportation better, its next 20 years of growth are going to make it much, much worse to drive a car or move freight.

“To get the most out of the infrastructure we’ve got, you’ve got to get people into other modes,” Zehnder said. “That’s part of preserving the capacity for people who need it.”

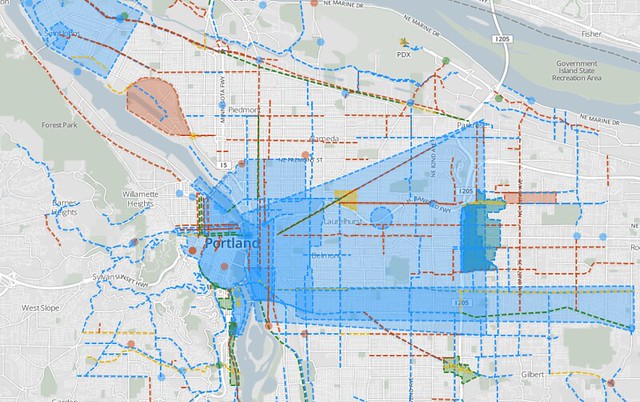

The other day, the Mercury and Oregonian called attention to a few of the dozens of transportation projects listed in the city’s online comp plan map app.

A few of the projects listed on the map ($200 million for the Columbia River Crossing, for example) are actually out of date, but most are not. There’s a biking/walking bridge over Interstate 84 at 7th or 9th Avenue ($8.3 million). A protected bike lane on N/NE Broadway from the Broadway Bridge to Hollywood ($3.5 million). Converting the old Red Electric railway to an east-west path from Willamette Park west to the Washington County line ($17.7 million). $560 million worth of other projects large and small to add streetcar lines, sidewalks and bike lanes.

There were a handful of exceptions, which neither the Mercury or Oregonian found interesting enough to mention: $50 million to widen SE McLoughlin Boulevard to six lanes. $50 million for a new freeway ramp connecting Interstate 405 to the Ross Island Bridge. Not to mention $464 million in projects focused more exclusively on truck and rail freight to the city’s industrial areas.

An update to the city’s transportation project list is due in November. Rivera said that list will be much shorter than the current one, reflecting new projections that assume less gas tax revenue and more pavement maintenance.

Advertisement

Still, Rivera and Zehnder didn’t dispute the notion that the city is unlikely to ever again spend millions to, for example, add a traffic lane to Burnside by pushing its sidewalks into what once were storefronts, or try to revitalize Lents by building a freeway through it.

“We’re a built-out city,” Zehnder said.

What does the city see itself becoming? Here are some “before” and “after” images the city released Wednesday to illustrate its vision for NE Glisan Street at 72nd:

For SE 122nd at Division:

For SW Barbur near Hamilton:

Looking at these concepts and talking with Portland’s top planners, I couldn’t help but wonder why, if this is what city leaders say they want, all the talk from the Portland Bureau of Transportation bureau is that the streets must be safe. Certainly that’s true — there’ll be no increase in biking and walking if people don’t feel it’s safer — but biking and walking are already extremely safe in the parts of Portland expected to grow the fastest.

For this plan to work, increasing safety won’t be nearly enough. Non-car transportation will need to get much faster, much more comfortable and much more convenient.

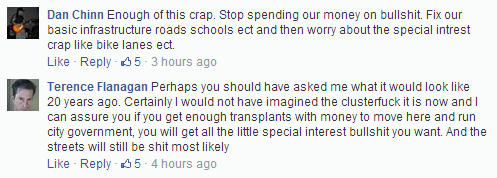

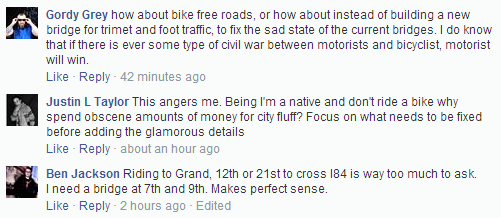

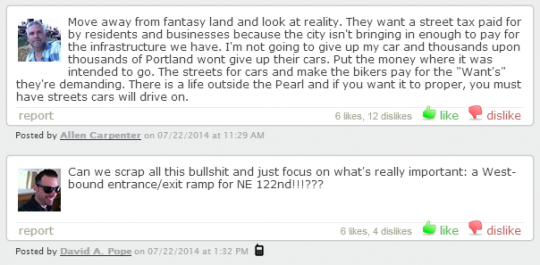

Then I read the comments people had left beneath the Mercury’s coverage, which had emphasized the 7th/9th Avenue bike/walk bridge.

City planners certainly have a clear vision for the future. What’s less clear is that most Portlanders share it. If Portland weren’t likely to grow by 50 percent in the next 20 years, better biking, walking and transit might just be luxuries. But if people move to the city at the rate its economists expect, increasing car-lite transportation will be a necessity.

As this comprehensive plan moves toward public approval over the next year, its future may depend on whether more Portlanders can come to face those facts.