With a homebuilt $300 pollution monitor strapped to his bicycle and seven years of Portland State University education in his brain, Alex Bigazzi has been leading a deep exploration into your lungs.

Bigazzi’s findings might be an argument for electric bikes, which let people move quickly through an area without exerting themselves heavily.

Since we wrote last year about the PSU Ph.D candidate’s research into the amount of pollution people ingest while biking, Bigazzi has been taking what the Portland Tribune called his “breakthrough findings” on a successful tour, authoring two upcoming journal articles on the subject and, last week, presenting them (slides, audio) at the city’s “Lunch and Learn” series about bike transportation issues.

By designing his own low-cost equipment, gathering data from his own commute and others’ and thinking critically about previous research, Bigazzi has taken the science of pollution ingestion to what you might call an obsessively practical new level.

Here’s some of what he’s found so far.

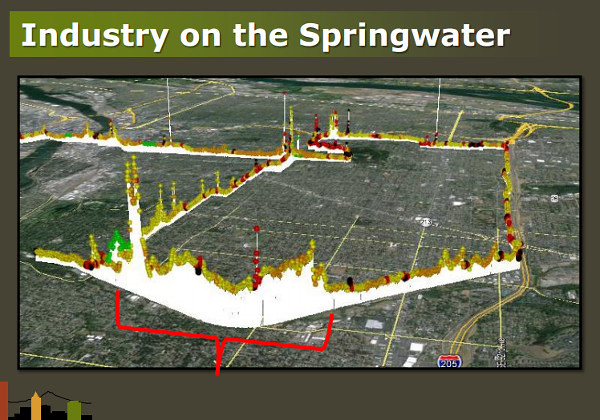

1) The Springwater Corridor is a surprisingly polluted route.

Bigazzi discovered that the air along the city’s best off-street path is actually some of the dirtiest, at least where traffic-related gases and grime are concerned.

“Even though we’re talking about traffic-related air pollutants, it’s not all coming from traffic,” Bigazzi explained last week. The many industrial developments near the Springwater (a former freight railroad), including Precision Castparts‘ three operation facilities for steel and titanium, send industrial solvents and other potentially harmful substances into the air.

But here’s one of the big insights in Bigazzi’s work: when it comes to biking, exposure to pollutants isn’t everything.

“That, it turns out, is where most people stop,” Bigazzi said. “We shouldn’t stop there because it’s only part of the health effects of traffic-related pollutants.”

2) Harder pedaling means more pollution per second — but fewer seconds of exposure.

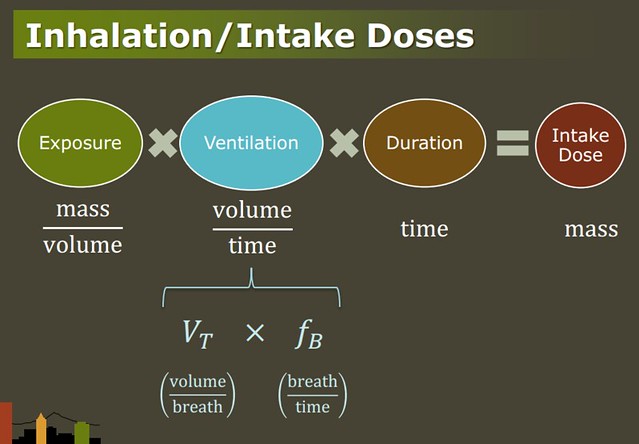

The biggest contributor to pollution intake, Bigazzi found, isn’t actually how dirty the air around you is. It’s how much of it you breathe.

“Ventilation completely dominates the exposure differences,” Bigazzi said. “The exposure differences are not that big.”

That creates an interesting mathematical puzzle: the harder your body works, the more pollution you breathe in. But the faster you move, the less time you’ll spend in the dirty air.

Advertisement

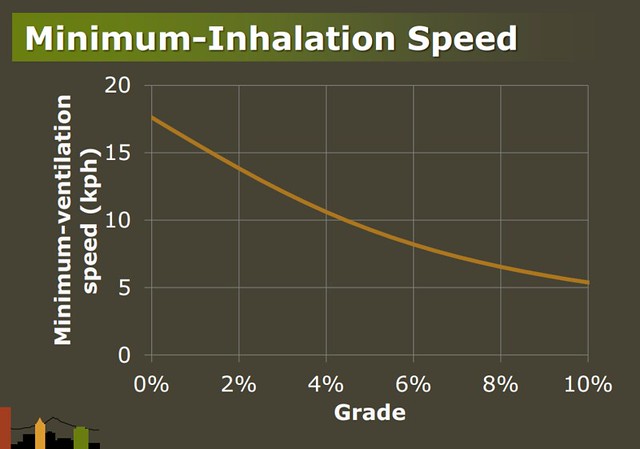

So assuming you’re headed to a place where the air is cleaner than it is along a roadway (Precision Castparts commuters, take note), here’s a curve Bigazzi constructed that shows the optimum speed to ride for various bikeway slopes. It’s expressed in kilometers per hour; the 17.5 kph “minimum ventilation speed” for a flat 0 percent grade is 11 mph.

For a steep 10 percent grade, the optimal speed would be just 3 mph; for a 4.5 percent grade like the one on Southeast Belmont near 11th Avenue, the optimal would be about 6.2 mph.

At Thursday’s presentation, one of the attendees made an interesting point: Bigazzi’s findings might be an argument for electric bikes, which let people move quickly through an area without exerting themselves heavily.

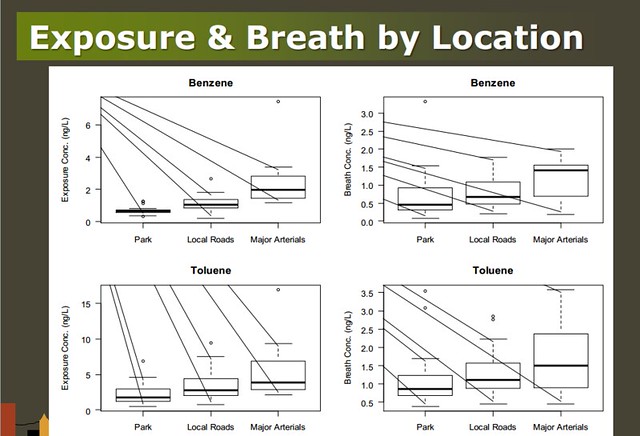

3) Biking on a big busy street is a lot dirtier than biking on a local street.

Based on these calculations and Bigazzi’s hard data, he found that biking along a major arterial like Powell Boulevard means ingesting three to five times more traffic-related pollutants than biking on a local street.

There’s been some study of pollution levels in protected bike lanes, Bigazzi said, and pollution exposure there seems to be “measurably lower than where a bike lane would be on the same facilities for traffic-related air pollution.” He said he didn’t have exact numbers on this phenomenon.

4) The good news: Pollution problems are outweighted by the huge health benefits of biking.

Bigazzi, who obviously rides a bicycle himself, is sensitive to the charge that because he’s found that people on bikes (or foot) are exposed to more traffic-related pollution than people in cars, he’s implying that biking isn’t healthy.

The opposite is true, Bigazzi said. The act that puts bikers and walkers in contact with pollution — exerting their lungs — is so inherently healthy that it more than offsets the pollutant’s damage, other scholars’ studies estimate.

“All of them found an order of magnitude or two difference in exercise benefits outweighing pollution risks,” Bigazzi said. “So the net benefit is likely to be much much higher. But air pollution is still a risk.”

The same is true, he said, of whether people should avoid biking on major streets. Not if that’d mean taking a car, he said.

“Bicycling is better than no bicycling,” he said. “But it’s even safer from a pollution point of view if you’re not on an arterial.”