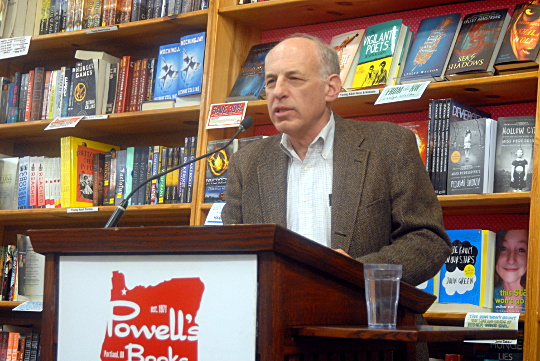

People who speak out against investments in density, biking and public transit may claim to be motivated by things like traffic, parking or crime, Ben Ross said Monday at Powell’s Books.

But though they might not realize it themselves, they aren’t. And that means that addressing their concerns won’t silence their worries.

That’s Ross’s claim, at least. A successful volunteer transit advocate from the inner suburbs of Washington DC, Ross is on tour for his book Dead End: Suburban Sprawl and the Rebirth of American Urbanism, in which he tries to explain the causes of the developed world’s urban revitalization and offer advice for navigating its politics.

“I think what we are really seeing here is a clash of two different value systems,” Ross told a packed room at Powell’s Books on Hawthorne Monday. “Over a century … we’ve built up a system of beliefs based on the idea that living in a single-family house and getting around in an automobile is socially superior to other forms of life.”

This association of suburbanism with wealth shaped the midcentury generations’ perceptions of cities, Ross said. But once the postwar economic boom put the suburban life within reach of most Americans, the children of the middle class stopped associating it with virtue.

“Historically, the idea of the single-family home with the automobile was for the upper-middle class, and it got copied by people further and further down the ladder,” said Ross, who spoke as part of 1000 Friends of Oregon’s McCall Society Speaker Series. “By the 1970s, having your own house with a front yard and moving in an automobile was no longer something that put you above other people. You had a more run-down house and a more run-down car, but you still drove to work.”

People who share the assumptions of the old system, he argues, can be confused or threatened by people who subvert it.

“If you look at any of the statistics, a large percentage of bicycle commuters is people who are too low-income to afford a car or are undocumented and can’t get a license,” Ross said. “But you never hear complaints about those bicycle commuters, because they’re not socially threatening. You hear complaints about people in Spandex.”

Ross said his research was mostly qualitative, based on other books and his own observations. But he said his one bit of data-driven research was to look at auto use by generation.

The decline in driving among young people is making headlines now, but he said it first showed up among young people around 1990 and has continued as that generation and those after it have aged.

“People who’ve been born since roughly 1970 are driving much less and living in cities more,” Ross said.

Ross’s lesson for advocates follows from his dualistic theory of urban politics: don’t bother negotiating with the hardcore opposition.

“The opposition is not really necessarily motivated by the particular objections it raises,” Ross said. “They have their reasons for their belief, whether or not they state them, and those are valid reasons.”

In a debate shaped by intractable assumptions about what people do or don’t want, logic isn’t much use either.

“Politically, every motivation is legitimate,” Ross said. “There’s no point in telling people they’re wrong if the real reason they’re against something, they’re right about. You just disagree with their value.”

Instead, Ross argues that advocates of urban life “should reach beyond what are often self-appointed neighborhood leaders and try to reach out to the grassroots.”

“Most people are somewhere in the middle; most people have some of each in them,” he said. “When we look out on the street, on Hawthorne Street, you are seeing one of the results of Tom McCall’s vision: this lively walkable street. … What you want to emphasize is that this success needs to be built on, that replacing some of the auto repair shops and parking lots with more of what everybody loves would be good for the community.”

Ross readily admitted that his thinking is shaped by his experience in Maryland. Listening to his insights, I wondered if they might be more useful in explaining suburban opposition to light rail than they are in explaining neighborhood-association opposition to apartment buildings.

But Ross’s explanation for the great decline of driving is interesting, and his case for urbanism — as a political philosophy that’s rooted, essentially, in a love of diversity — is compelling.

“It has to be presented in a way that this is not charity,” he said. “This is something that we’re doing to make something that is better for us. It will make all our communities better.”

— The Real Estate Beat is a weekly column sponsored by real estate broker Lyudmila Leissler of Portlandia Home/Windermere Real Estate. Let Mila help you find the best bike-friendly home.