Seven miles is an important distance in the world of bike transportation.

It’s about the distance a casual city rider can pedal in an hour, which studies show is the upper limit of the time most humans prefer to commute. It’s the distance where, even in the Netherlands, public transit trips become more popular than bike trips (and car trips are eight times more common than either).

So as Portland’s apartment rents have jumped an average 11 percent in the last year, with the tightest markets in North and inner Northeast Portland, the city’s biking population has felt it — in either their wallets or their thighs.

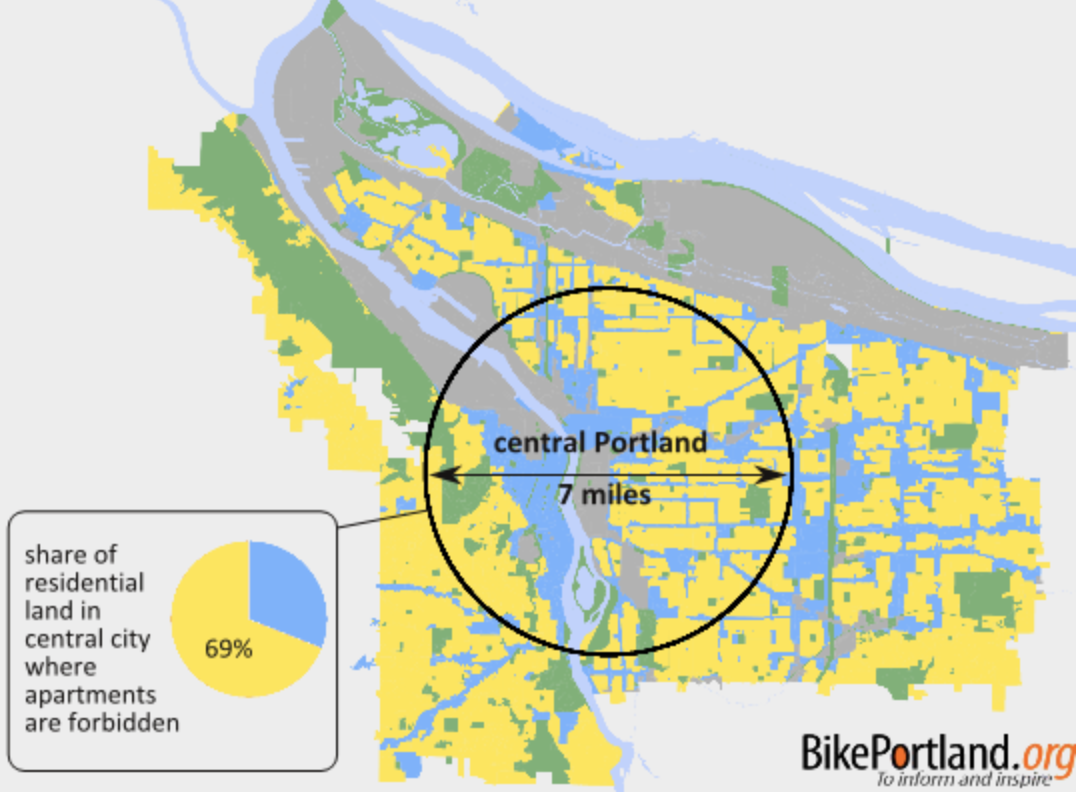

Here’s one factor at play in one of the country’s most persistent urban rental shortages: in two-thirds of Portland’s central seven miles, it’s illegal to build a multi-family building.

It’s a broad swath of the city that includes Hillsdale in Southwest Portland, Eastmoreland, Woodstock and Foster-Powell in Southeast. It grazes 82nd Avenue and Rosa Parks Way, taking in the edges of Cully, Woodlawn and Arbor Lodge. Inside the circle, only 31 percent of residential land allows multifamily construction. (Citywide, the figure is 26 percent. Some residential construction, including apartments, is also allowed on “general employment” land, which isn’t part of the “residential” land ratio here.)

Even advocates for more housing don’t say apartments or condos should be allowed throughout this central area, or even most of it. But as neighborhood associations submit their requests this month for the city’s next comprehensive zoning plan — with some, like Eastmoreland, requesting less density — some are calling attention to the anomaly of so much land in the middle of Portland being reserved for single-family homes.

“In Northwest, the zoning allows high-density development, and the market has responded,” said Eric Engstrom, principal planner at the city’s planning bureau. “In Buckman, it is zoned single-family exclusively. … Probably without zoning, Buckman would be much denser.”

Some Portlanders like the current system, Engstrom said. Others don’t.

“I think zoning’s a valid policy tool that can achieve things, but it can be used for good and for ill,” said Ben Schonberger, senior planner at Winterbrook Planning and a board member for the housing-affordability nonprofit Housing Land Advocates.

Schonberger acknolwedged that new multifamily units are usually more expensive than older buildings, including the repurposed single-family homes they sometimes replace. But he said they prevent rents on the old units from spiraling upward even faster.

“Those people are coming to Portland regardless,” Schonberger said. “And either they’re going to fill a unit in an existing neighborhood and push the people out of there, or they’re going to occupy the shiny new unit. … It doesn’t feel like [the units in a nice new building] have any impact on affordability, but they do. It’s spread out across the whole metropolitan area by pushing everybody’s rents down by a couple dollars a month. And that’s really hard to see.”

The political problem, Schonberger said, is that the people who would benefit from “upzoning” to higher densities are the ones “who haven’t even moved here yet.”

“It’s a student who wants to go to PSU and wants a reasonable rent,” Schonberger said. “But he right now is living in Ohio and thinking, ‘Well, gee, I want to move to Portland but can’t afford it.'”

But Jamaal Green, a Portland State University Ph.D candidate who moved to Portland from North Carolina, said that though upzoning may indeed help people like him, it’s less useful to people in poverty.

“We do have a supply problem which upzoning could maybe help to dent,” said Green, who writes frequently about housing and transportation under the name Surly Urbanist. “Just don’t blow smoke and tell me that it’s for low-income people, because it’s not.”

“If you’re trying to address housing affordability at the bottom of the market, your upzoning has to be combined with something, like a combination of upzoning and inclusionary zoning,” he said, adding that more support for the state’s popular low-income housing tax credit program would help too.

Schonberger said he too supports changing state law in order to allow inclusionary zoning, which could require new buildings to preserve some lower-rent units for lower-income residents. But both he and Green questioned whether IZ alone could have a big effect on affordability.

“Most people, even most poor people, are living in market-rate housing,” Schonberger said. “And if market-rate means you have to live way back in Rockwood, that’s what you’re going to do.”

Correction 4/24: Because the city allows limited residential development on “general employment” land, some of the gray areas in the map above allow multifamily construction. An earlier version of this post did not reflect this.

— The Real Estate Beat is a weekly column sponsored by real estate broker Lyudmila Leissler of Portlandia Home/Windermere Real Estate. Let Mila help you find the best bike-friendly home.