(Photos by M.Andersen/BikePortland)

Call it the people’s density.

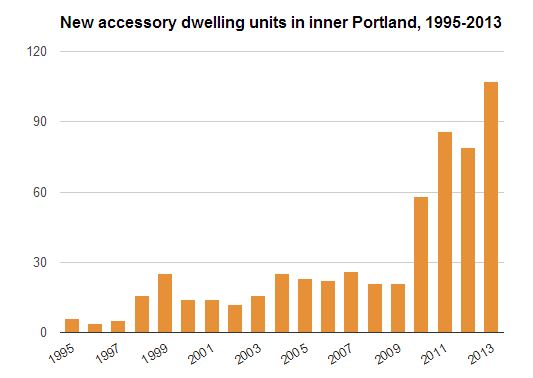

Four years after Portland slashed its transportation and parks fees for “in-law” units and other secondary dwellings in hopes of increasing the housing supply in its most in-demand neighborhoods, the city has gotten its wish.

Though they’re still far from common — it’s only about 3 percent of new dwellings citywide, and fans say those that exist remain in hot demand — the backyards, cellar doors and underused garages of Portland’s central neighborhoods are rapidly filling up with “accessory dwelling units,” which the city defines as living spaces of 800 square feet or less that have an entrance, bathroom and kitchen to call their own.

Fewer than half of them offer on-site auto parking. Then again, one in five households that live in them don’t own a single car. (Another 63 percent own one car.) And though banks still haven’t figured out a standard way to finance them — more on that in a future Real Estate Beat post — they’re popping up like mushrooms.

“In some of the inner neighborhoods, it’s as much as 10 to 15 percent of all new dwellings are ADUs,” said Eric Engstrom, the city’s lead planner on the issue.

According to a September 2013 survey that also gathered auto ownership, demographic information and many other details about ADU residents, the average rent of a Portland accessory dwelling unit was $811 plus utilities.

(Source: Portland Bureau of Planning and Sustainability.)

“There is this huge demand for the kind of housing that ADUs represent,” said Kol Peterson, who bought a traditional single-family house near Alberta Street in 2011 and built a new 800-square-foot home in its backyard for $110,000. Today, Peterson and his wife rent out the larger original house, live in the smaller one, and expect to fully recoup their investment in two to three years.

Some of the recent growth isn’t actually new construction. Many people are taking advantage of the fee holiday to bring longtime units up to code and make them legal. But Peterson said it makes sense that there’s “a crushing need, a huge demand” for ADUs in Portland and other growing U.S. cities, Peterson said.

Three-quarters of the households in Portland are “individuals, couples without children, or individuals living together,” Peterson said in an interview. “But the housing stock that we have is three-quarters single-family homes.”

Neither of those statistics has actually changed much since the turn of the century, which is when Portland eliminated its rule (still common in many cities) that the owner of an ADU must live on the same lot. And even the city’s fee cut slices at most $10,000 off the price of developing an ADU; more than half of ADUs cost $80,000 or more to build, according to the 2013 survey.

(Photo courtesy Moray)

What has changed, though, is Portlanders’ hunger for homes in walkable, bikeable, high-transit neighborhoods. Engstrom said that’s helped give rise to a cottage industry (so to speak) of builders and developers who have experience with ADUs.

“We were one of the first cities that I’m aware of to legalize them, but it’s been more recently that they’ve kind of taken off as an economically viable thing,” Engstrom said.

The specialist contractors include Orange Splot, Hammer and Hand and Green Hammer. They’re a rising share of the rental market, too: you can check out the current listings with this Craigslist search, recommended by Peterson.

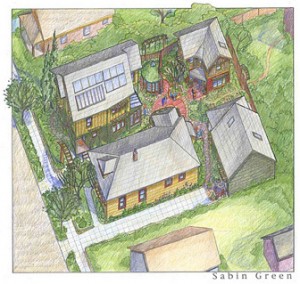

two small homes and two ADUs developed by

Orange Splot LLC.

ADUs in the Portland area even have their own niche website, AccessoryDwellings.org, published by a few local ADU experts. As part of a temporary project funded by the Metro regional government, it’s now being updated almost every Friday with a new “case study” about a local ADU.

The case study project’s manager, Lina Menard, said she thinks Metro, the city and state all have an interest in increasing the supply of ADUs because it’s a way to increase housing supply without dramatically transforming neighborhoods or scrapping older homes. It also adds “flexibility over the course of people’s lifespan,” helping people age in place or with the help of their families without sacrificing privacy.

“This is a way to reconnect multigenerational families,” she said. “The idea of having nuclear families in single-flamily homes in the suburbs — we talk about that as the ‘traditional household.’ But it wasn’t.”

Engstrom said he also sees ADUs as a way to increase the population of a given neighborhood enough for more of the city’s commercial corridors to support everyday services like neighborhood grocers, hardware stores and coffee shops within walking distance.

“To the extent that we can have more people near them, it makes those streets more livable more likely to have basic amenities instead of just being trendy restaurant rows,” he said.

— The Real Estate Beat is a weekly column sponsored by real estate broker Lyudmila Leissler of Portlandia Home/Windermere Real Estate. Let Mila help you find the best bike-friendly home.

You can sign up to get an email of Real Estate Beat posts (and nothing else) here. Correction 2/26: An earlier version of this story incorrectly described the funding of AccessoryDwellings.org.