bike share station at downtown’s Director Park.

As public bike share systems continue to become standard public services in cities around the country, we figured it was time to learn more about what’s in store for Portland.

In June, the Portland Mercury devoted part of its annual bike issue to a system that remains in its fundraising stage. Last month, Willamette Week breathlessly reported that the city is considering greasing the wheels of sponsorship by offering to cover the up-front cost as a loan.

Before anyone decides to turn the planned Portland Bike Share into a public dartboard by exploiting public confusion about it, Jonathan and I decided it was high time to look at the documents behind Portland’s bike share plan and air them in full with our own honest analysis. So we requested copies of two public documents: Alta Bicycle Share’s 97-page proposal to the City of Portland, which came in first place after a competitive bid process, and the contract both parties subsequently signed to provide the service.

Here’s the most interesting stuff we found.

1) Bike share memberships will probably cost about $75 a year.

Here’s what Alta was expecting to charge for bike share in Portland as of early 2012:

The price structure on the left, which Alta estimates would result in 67% higher ridership than the one on the right, sets a somewhat higher entrance fee ($75 per year or $5 per day) but a lower per-ride fee (free for the first half-hour and less than $6 for up to 90 minutes). “Pricing Model 1” is the same price structure being used in almost all new U.S. bike share systems.

One thing to keep in mind, though: Annual memberships aren’t the most important factor in the system’s success. That’s because…

2) Bike share would be used mostly by Portlanders, but paid for largely by visitors.

Though people with annual memberships — almost entirely locals — would account for 80 percent of trips in year 2, Alta estimates they’d account for less than half the system’s revenue. “Casual” 1-day and 3-day subscriptions — mostly tourists and other visitors — would cover 70 percent of user revenue, largely because they tend to take more trips that last longer than 30 minutes.

Alta bases all the above projections on “a bike share demand model from empirical data collected in other cities operating bike share including Montreal, Washington DC, and Boston.” They’re also consistent with trends non-Alta experts have described to me over the last two years — though I wonder if, as more travelers get savvy about how bike share works, they’ll also become less lucrative.

3) Each bike would cost $1,103.

(Photo © J. Maus/BikePortland)

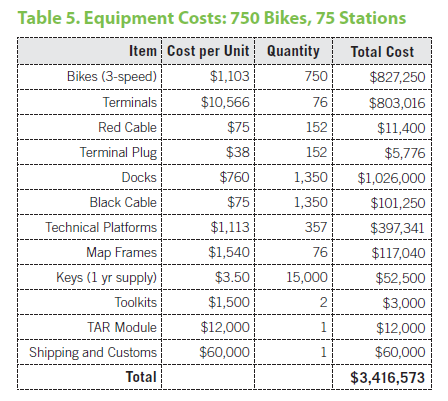

That’s a lot of money for a 50-pound three-speed. But these are durable bikes with built-in electronic components. Sometimes you’ll hear people overstate the cost of shared bikes by dividing the full cost of the system launch by the number of bikes provided; this would be a little bit like estimating the cost of a new TriMet bus by dividing TriMet’s annual budget by 650. Here are Alta’s actual hardware costs:

4) Bike share doesn’t look like a high-profit business.

How, exactly, does Alta make money? It’s hard to find much fat in this contract.

Out of a total $1.9 million expenditure in year 2, Portland Bike Share would only send $124,800 to Alta for “corporate support,” a figure that presumably includes profits for the company’s owners. Even if all of that went to profits (as opposed to paying the wages of Alta’s corporate employees, rent, and so forth), that’s just 6.5 percent of expenditures, a pretty low profit margin for such a new industry. Alta may be counting on profit to arrive over time, once its systems are in place and operating smoothly — but this would seem to explain why other companies aren’t jostling to compete with Alta.

Since Alta was a bike planning and design firm (one of the country’s first) before its owners decided to start a bike share company on the side, it’s possible that the firm started thinking about bike share as a way to generate work for their planners, to which Alta Bicycle Share seems to hand its station siting subcontracts. If so, the rapid growth of Alta’s bike share business may have taken the company by surprise, especially considering that…

5) Alta Bicycle Share has probably outgrown Alta Planning + Design in revenue by now.

From Alta’s proposal: “Alta Planning + Design had gross revenues of $10.7 million in 2011. … Alta Bicycle Share had gross revenues of $9.6 million in 2011.” That’s from before Alta launched bike share in New York City, Chicago and the San Francisco Bay area.

6) Bike share would employ about as many Portlanders as a big bike shop.

Alta will hire a general manager (“we have already identified a number of suitable candidates for this role,” Alta wrote in early 2012), a marketing manager, an administrative manager, an operations manager, shift managers, a head bike mechanic, a head station technician, and several part-time “street team” members and in-shop bicycle mechanics. All except the last are listed as “local hires.”

7) Alta promised to try to make bike share work for low-income people.

“Historically underrepresented and economically disadvantaged people will make up not less than 50% of total employment hours.”

— Alta Bicycle Share proposal to City of Portland

In its contract, Alta promises to provide “up to 500 discounted memberships to be purchased by the City and/or other organizations for low income residents or individuals from traditionally underserved communities for $35 or lower.” That’d be a tiny dent in Portland’s low-income population, but it’s also 10 percent of the system’s total users in year 2.

Alta has also agreed that “historically underrepresented and economically disadvantaged people will make up not less than 50% of total employment hours.” (This promise, though worth noting, won’t require as much effort as it might seem: the contract specifies that “historically underrepresented” includes women, and “economically disadvantaged” includes “low-income Portlanders.”) This effort will be overseen in Portland by a “High Roads Committee” with members drawn from the Coalition of Communities of Color and other groups such as “the Coalition for a Livable Future, Worksystems Inc., Oregon Tradeswomen Inc and New Avenues for Youth.”

There’s been a lot of discussion of whether bike share, which in Portland is being funded by a federal grant intended to promote “equity,” will actually be used much by people most in need of low-cost transportation. I loved this set of practical ideas from BikePortland reader Alex Reed for how to actually make bike share relevant to poorer people.

8) If the system is actually going to launch in “spring 2014,” it had better get a sponsor right away.

From Alta’s proposal: “In our experience, a full launch takes approximately six months from the time funding is secured and contracts are signed.”

9) Portland is asking corporate sponsors to cover more of bike share’s cost than similar cities have.

In its first year, Denver B-Cycle brought in $2500 per shared bike from lead sponsor Kaiser Permanente; Minneapolis’ Nice Ride brought in $1400 per bike from Blue Cross-Blue Shield of MN. For its “launch” period, Portland is hoping to bring in $3700 per bike from sponsorship.

This isn’t necessarily unreasonable for a system that, unlike those two peers, is expected to operate year-round and attract about three times as many trips in its first year as Nice Ride did. But it’s a lot of money. In all, 60 percent of the startup cost of Portland Bike Share — $2.8 million out of $4.6 million — is supposed to come from from private sponsors, compared to about 33 percent in Denver and 33 percent in Minneapolis. (To be fair, Denver B-Cycle scored another one-third of its startup costs from $1 million left over from the 2008 Democratic National Convention, whose organizers were eager to make friends in a swing state.) To share the burden, Alta has suggested that not all the money has to come from the same company.

It’d be silly to claim that high sponsorship targets make Portland bike share a bad investment, because it’s hard to put a price on such a unique service. In the month after New York’s bike share system launched, public opinion of its title sponsor CitiBank improved rapidly. Also, public bike share is a far less risky investment than it was in 2010. But bike share has struggled to materialize in Portland, and it’s hard to imagine that the high sponsorship expectations are unrelated.

How did this happen? Well, bike share was sold to Portland City Council by backers, including former Mayor Sam Adams and numerous others, who said it could be paid for without any local money. A representative of Regence Health Services testified in favor of the deal; it was easy for bystanders to assume that the major health insurer had all but signed on as lead sponsor. But it hadn’t. Moreover…

10) Alta and the city don’t really have a deadline to roll this out.

We’re sure they’re as eager as anyone to get this system running already. That said, the only reference to a solid deadline anywhere in the bike share deal is a requirement in the contract that Alta “negotiate” with the city to provide “a desired minimum” of 50 bike share stations “in a timely manner”:

“If the agreed-upon System Financing Agreement does not provide sufficient revenues for launching a system with 750 bicycle and 75 stations for five years, the City and [Alta] shall negotiate a scaled approach to launching bike share in Portland in a timely manner that still achieves the targets set. … The desired minimum system size is a minimum of 50 stations and 500 bicycles. The Financing Report, at a minimum, must secure the monies for five years of system operation.”

According to Metro, the agency that oversees the federal money behind Portland bike share, there’s no firm deadline for the city to spend its grant, either.

“We do have a schedule for the bike share project, but we’ve gone into this understanding that some flexibility on this was going to be necessary,” Metro grant manager Ted Leybold told us Wednesday. “There’s no looming deadline that the project needs to meet, but we’re trying to make sure the project moves along.”

Is this good for bike share? Maybe not, actually. When it comes to fundraising, urgency can be the key to a deal.

Biking in Portland is so pleasant, and bike share in other cities is so obviously popular and successful, that it seems likely to be an asset to whoever is behind it: city leaders, Alta, whatever private sponsors end up being involved. But it’s possible that some sort of a deadline — with or without a bigger contribution from the public — would be required before our city can join Boston, Charlotte, Chicago, Columbus, Fort Worth, Houston, Kansas City, Long Beach, Louisville, Madison, Miami Beach, Minneapolis, Nashville, New York City, Oklahoma City, Omaha, Salt Lake City, San Antonio, San Francisco and Washington DC to take this seemingly sensible leap.

Correction 9/4: An earlier version of this post said both documents were previously unpublished. In fact, the Mercury published Alta’s contract in March.