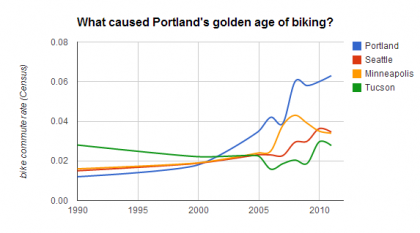

2002 to 2008.

When we talk about the amazing growth of bicycling in Portland, those are more or less the years we’re talking about. Before 2002, to look at the behavior of Portland commuters, this was just another outdoorsy city on the West Coast; since 2008, it’s been just one more mid-size metro area with an increasingly lively central city.

But something strange and wonderful happened in between. Over the last week, people around the country have been asking why, and we’d love to know what the BikePortland community thinks.

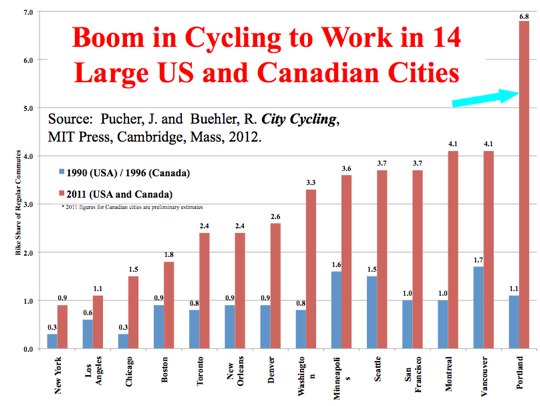

Noted bicycle researcher John Pucher got the conversation going with an email that was discussed last week by Seattle Bike Blog. Pucher used Census data to show how, in 1990, Seattle was one of North America’s leading bike cities. In fact, Pucher wrote, “Seattle had considerably more cycling than in Portland with 1.5% vs. 1.1% bike mode share.” But by 2011 there had been a “a truly stunning reversal” with Portland bouncing up to 6.8% compared to Seattle’s 3.7% (and all the other cities had similarly unimpressive growth).

What happened? Why did Portland cycling rates increase so much more than other leading bike cities?

It’s not because of our bike lanes. Many Portlanders know how non-driving Mayor Vera Katz, bike-friendly Transportation Commissioners Earl Blumenauer and Charlie Hales and hard-charging Bicycle Coordinator Mia Birk worked together to create a great network of basic bike lanes in the late 1990s, culminating with widening the Hawthorne Bridge sidewalks in 1999 and opening the Eastbank Esplanade and lower deck of the Steel Bridge in 2001.

According to PBOT stats, between 2002 and 2008 we added only 29 total bikeway miles to the entire network (going from 253 in 2002 to 274 in 2008).

So what gives? Gas prices spiked from 2004 to 2007, of course, but that happened everywhere, so it doesn’t explain Portland’s unusual behavior. And part of the story is definitely that it took Portlanders a few years to realize how solid our bike network had become. But we think there’s more to this conversation, so Jonathan and I want to share five other theories worth thinking about.

1) Bike Fun.

This is probably our favorite theory — this blog, after all, began in 2005 as the “Bike Fun Blog” on Oregonlive.com. As you can read on the website of the bike-fun group Shift, the PedalPalooza bike festival began as Bike Summer, a traveling event that came to Portland in 2002 and fizzled a few years later. Zoobomb also began that year, made possible by a recently built light rail line that happened to include the deepest station in the Western Hemisphere — and an elevator.

The Critical Mass movement, which mixes fun and protest, was also strong in Portland for years but died down around 2006.

But when it comes to improving biking, bike fun is no laughing matter. The influence of Shift and the impact of the hundreds of fun and creative bike events in Portland each year cannot be overstated. Just look at the numerous local activists, advocates and city employees who’ve taken part in everything from bike moves to Breakfast on the Bridges. Attend any big hearing on bike issues in this city and you’ll see many people who regularly attend bike fun events. It make look like just a bunch of happy people in funny costumes and freaky bikes, but it’s a source of social connections, institutional knowledge and collective action.

above and beyond to make biking better.

(Photos © J. Maus/BikePortland)

2) Great city staff.

Bike lanes aren’t the only infrastructure that matters. Think about details like the timing of downtown traffic signals so that a vehicle traveling at 14 mph will catch all the green lights — a change made in 2002 thanks to a grant from the Energy Trust of Oregon — or the openings for bikes at traffic diverters on NE Tillamook Street or SE 20th Avenue. Those touches require City staffers we like to call “advocrats” (a combination of advocates and bureaucrats).

Not all bikeways are created equal, either: good lanes, even when they’re marked only by paint, require careful choices about width, placement, color and so on. For various reasons, Portland’s been lucky enough to attract and retain people who’ve become nationally known experts on bike-friendly street design. Some of them even helped write the definitive guide to urban bikeway design and they’re often asked to share their knowledge to audiences around the world.

3) Mature communication channels.

Most growing cities hire experts to build ever-larger roads for more and more cars. In 2004, the City of Portland decided to hire a small team of experts to persuade people to not fill up the roads with their cars in the first place.

The city’s SmartTrips program, which started as a contract job in 2004 and was brought in-house in 2005 and 2006, employs a handful of city workers who encourage people to drive less by targeting an area of the city and organizing bike events, mailing them free bike maps and generally swamping them with bike-related resources.

SmartTrips is just one of many mature communications and marketing channels in Portland that spread cycling. We are also lucky to have: the KBOO Bike Show (founded in 2001); the Bike Commute Challenge, a Bicycle Transportation Alliance contest ramped up during the aughts that is basically a spiffy marketing operation for bike commuting; OR Bike, which promotes the many fun organized rides in the region; and of course this website, which has become a widely read media source in its own right (it’s also worth noting the vast increase in cycling coverage from other local media outlets who get their story ideas from us).

4) Active activists.

Portland is lucky to have many residents who care deeply about bicycling and are willing to invest their own time to make it better. We have more non-profits per capita than any other city in America (so says the National Center for Charitable Statistics) and enough smart and engaged citizen activists that we can tackle issues of almost any size without asking for permission. Over 1,000 people have graduated from through the free PSU Traffic and Transportation Class armed with the knowledge to make change in their neighborhoods.

Groups like Active Right of Way, Friends of Barbur, Swift Planning Group, and many others know where, when, and how to push their agenda forward. The savvy and smarts of these activists combined with the work of professional advocacy groups like the Bicycle Transportation Alliance and the Community Cycling Center — which is then amplified here on the Front Page — creates a powerful force that politicians and policymakers must reckon with.

(Photo: Matt Haughey/Flickr)

5) A positive feedback loop.

This one is pretty simple: Once a city becomes known as great for biking, it attracts people who like bikes. These people support bike culture and vote for politicians who build bike infrastructure. And as the bike scenes everywhere from Indianapolis to Pittsburgh keep getting better, Portland’s reputation may be the strongest thing we have going for us.

Those are our best theories. What are yours?

Publisher/Editor Jonathan Maus also contributed to this story.