Much has been written lately about a “bicycling renaissance” that has taken hold in America. At the NACTO Designing Cities conference here in New York City, I’ve had the opportunity to learn about the reality behind that renaissance and I’m happy to say that it’s real. Nowhere was that more apparent that at a panel discussion I attended today titled, 8-80 Bikeways: Designing protected bikeways and bicycle boulevards to accommodate a broader range of users. The session featured updates on bikeway development from four cities: Portland, Indianapolis, Chicago and New York City.

made possible by:

- Planet Bike

- Lancaster Engineering

- Readers like you!

Most of you have heard about the need to attract people to bicycling that fall into the “interested but concerned” category. That phrase — which is now used by transportation officials across the country — was coined by the City of Portland’s Bike Coordinator Roger Geller back in 2006. It’s meant to describe the estimated 60% of the population that would like to try biking, but are too worried about safety and other issues to do it. Another way to think about that same concept is designing streets that appeal to the “8-80” demographic. As far as I know, that phrase was coined by the former City of Bogota Commissioner of Parks Gil Peñalosa (he’s now executive director of a non-profit by the same name). It’s used to describe the goal to have a network of bikeways where people young (8) and old (80) would feel safe navigating.

Martha Roskowski.

(Photo © J. Maus/BikePortland)

The session was moderated by Martha Roskowski, the director of the Green Lane Project. When it comes to attracting this broader range of people to bicycling, Roskowski believes there’s no substitute for high-quality, separated bikeways. Encouragement programs are important, she said, but they’re limited. “We can’t market out way into getting these people to ride.”

In his presentation, Geller acknowledged that even Portland (which was referred to by me as “that shining bike city upon a hill” by NYC DOT Commission Janette Sadik-Khan) has a lot of work to do. He shared the the highlights of Portland’s bike infrastructure; our 85 (and counting) on-street bike corrals, our neighborhood greenway network, and our protected bikeways like Cully Blvd, SW Moody, SW Broadway and SW Stark/Oak. But Geller knows what we lack is a connected network. “We need to build it even better,” he said, “We need to develop an entire network of protected bikeways.”

Geller pointed to the project currently being constructed on NE Multnomah St, where PBOT is re-striping the lanes and reallocating space to provide room for protected bike lanes. He called the plans, “A poor person’s cycle track,” meaning while we are re-working the space, the project isn’t building out the facilities to their full potential. At intersections with bus stops, for instance, PBOT has “mixing zones” where the bike lane ends and people will navigate with bus operators. “Ideally,” he said, “what we’d do is have a transit platform extended at the corner and buses would stop in traffic to board and deboard; but we can’t afford that, so we’re doing the mixing zone as a test to see how it works.”

“Are we an 8-80 city? No. We’re probably a 13-70 city; but we’re getting there.”

— Roger Geller, City of Portland Bike Coordinator

In his final analysis, Geller made an honest assessment: “Are we an 8-80 city? No. We’re probably a 13-70 city; but we’re getting there.” Geller said PBOT is in an “evolutionary process” and that “change is incremental.” He also told session attendees that he believes the barriers to doing more bold bike projects (perhaps like the ones New York City is doing) “are more political than practical.” “We don’t have the support from businesses or from the community that we need to re-purpose space from cars to bikes. And we don’t have support for the money we need to do it. Yes, bikes are a cheap date; but we do need some money.”

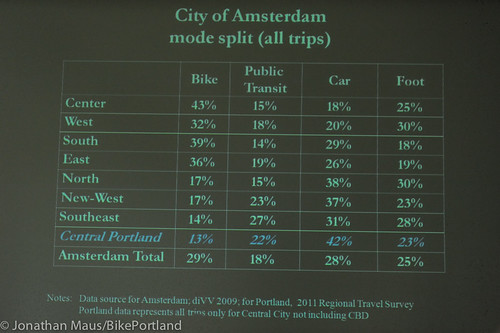

Geller shared the recent bike commuting numbers released just this week from the Metro Travel Survey. That survey revealed that 13% of Portlanders commute by bike within the central city/inner neighborhoods (excluded the central business district). He compared Portland’s numbers to bike commuting rates in Amsterdam. “That makes us an O.K., outer suburb of Amsterdam… So the best part of Portland is like the worst part of Amsterdam.”

While Portland enjoys an illustrious (and perhaps mythical) reputation for bicycling, Indianapolis is probably on the other end of the scale. But even there, the renaissance is real. Jamison Hutchins, the Bicycle and Pedestrian Coordinator for the City of Indianapolis, titled his presentation: From Zero to Hero. In 2007, they had less than one mile of bike lanes. But in the last four years — thanks in large part to support from their Mayor Greg Ballard — they’ve now got 67 miles of bike lanes. Their crown jewel, and perhaps one of the best examples of an 8-80 bikeway in the entire country, is the Indianapolis Cultural Trail.

The Cultural Trail is a $64 million (using a mix of private, local and stimulus grant funding), nine-mile path that loops through the city. It includes a separated cycle-track with signal priority and separate walking path. “Besides its functionality,” said Hutchins, “It’s just an amazing piece of awesomeness.” The path has spurred residential real estate development as well as a thriving new crop of businesses. It’s also provided momentum for other initiatives like the Indy Bike Hub parking facility, a newly passed complete streets policy, and a bike share system coming in 2013.

This year, for the first time ever, Hutchins said, the budget for the City of Indianapolis will include a dedicated revenue stream for bicycle improvements. According to to Hutchins, it was all possible because of Mayor Ballard. “He’s a Republican, and he understands bicycling from an economic development standpoint. He realizes we have to be able to compete with the Portlands and the Chicagos to attract the best talent so he’s given this top-down command to the engineers that it’s not all about cars anymore.”

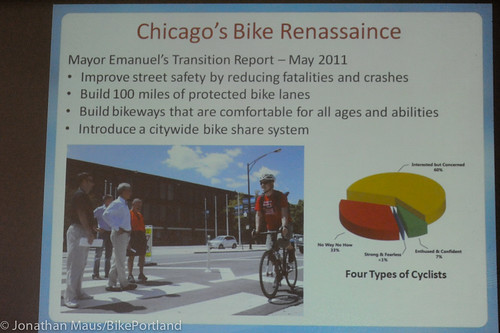

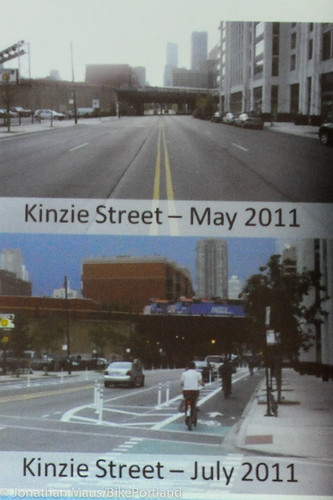

Speaking of Chicago, city officials there are building bikeways at a dizzying pace after a major proclamation by Mayor Rahm Emanuel in 2011 to build 100 miles of protected bike lanes by May 2015. Mike Amsden, the City of Chicago’s Bikeways Project Manager, said that effort has sparked a “bike renaissance” in Chicago over the past year.

“In one year and four months, we went from nothing, to having the second most protected bike lanes in the country.”

One key way they’ve been able to push bike projects through quickly is by leveraging the planned arrival of their bike share system. “We’ve got to have safe streets for people to ride on before bike share gets here. We’ve been able to use bike share as political leverage to take road space away from cars against the objections of some of our engineering staff.” Right now, their famous “loop” road has only a narrow, standard bike lane. But with bike share on the way, Amsden says they are moving forward with plans to build a two-way protected bike lane.

Moving to implement major bikeways so quickly been challenging. “It’s not easy moving fast,” Amsden said, “you piss off a lot of people when you do that.” He expressed regret that he and his staff simply don’t have time to do the necessary outreach to make projects successful from the outset. Another challenge is how to deal with street sweeping and snow removal once bollards and other separating features have been installed. They’ve been using a donated pick-up truck and Bobcats to do the plowing; but that’s not a feasible, long-term solution. Amsden said they’ve been testing a variety of sweepers and snow removers and he’d be happy to share what he knows (which is great, because I’ve heard PBOT engineers used the inability to sweep/maintain separated bikeways as an excuse to not implement them).

Perhaps the one American city coming closest to the 8-80 bikeways ideal is New York City. They’ve been getting so much praise in the bike world lately that it was actually a bit refreshing to hear the NYC DOT’s Director of Bicycle and Pedestrian Programs Josh Benson, share a project they got wrong. At least initially.

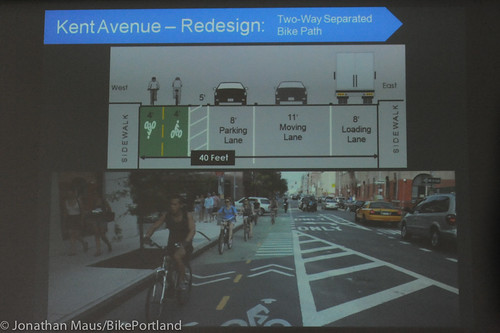

Benson shared a case study of their Kent Ave project that was completed in 2010. Kent Ave. was an industrial corridor along the East River waterfront with a typical, two lane cross-section with auto parking on both sides (like many Portland streets!). When the local community board (similar to our neighborhood associations) voted in support of a waterfront greenway path with no on-street auto parking, the NYCDOT went to work on the design. They implemented six-foot, curbside bike lanes. Unfortunately, the design didn’t work. Neighbors and business owners hated it: Speeding became a big problem due to the lack of parked cars to slow people down; industrial businesses couldn’t get curbside access for their trucks; many people parked and drove in the bike lane, and so on.

“So we redesigned it,” said Benson, “We used the feedback as an opportunity to make it a much better design and we got there by talking to everyone who cared about this street.”

The final design was much more creative. They turned it into a one-way street, installed a two-way buffered bike lane, and added a lane for parking and lane for loading. The result? A 200% increase in weekday bike traffic with a whopping 2,500 average bike trips on the weekend (1,700 on weekdays). And people liked it. “We turned it from our worst failure to one of our biggest successes.”

——

What can Portland learn from these cities? Where will we build our first 8-80 bikeway?

— This post is part of my ongoing New York City coverage. I’m here for a week to cover the NACTO Designing Cities conference and the city’s bike culture in general. This special reporting trip was made possible by Planet Bike, Lancaster Engineering, and by readers like you. Thank you! You can find all my New York City coverage here.

—-