On Tuesday night nearly 200 people came together for a ‘Community Forum’ to learn about a neighborhood’s past and share their opinions on the myriad issues surrounding the City’s North Williams Avenue Traffic Safety Operations Project.

The size and makeup of the crowd made it clear that this project has come very far from its humble beginnings. What started back in May 2010 as a project to improve bike access on Williams Avenue has become something far greater.

Consider who was in the crowd: There were many long-time residents, several of whom have lived in the area for over 30 years. There was also an impressive showing of City leaders including, Mayor Sam Adams, PBOT Director Tom Miller, Planning Commissioner Chris Smith, Portland Development Commission Director Patrick Quinton, Bureau of Planning and Sustainability Director Susan Anderson, and others.

In many ways the night felt like a deja vu. It was about seven months ago that the project’s first open house was held at the same location (Immaculate Heart Church across from Dawson Park). While the project has come very far in terms of awareness and community involvement, last night also felt like it was starting over.

Just like at the open house in April, feedback forms were passed out and the City got an earful of opinions about the street; what works, what doesn’t, and how people want it to work in the future.

While Mayor Adams probably didn’t even have this project on his radar in April, he was front-and-center Tuesday night. Here’s how he opened the meeting:

“The one constant of any city is change. But in this particular neighborhood there are special vulnerabilities, factors, sensitivities, and facts and realities, that this community has to grapple with. This part of town was subject to racist and discriminatory policies at a time when the City, the Portland Development Commission, the County, the hospitals, the Oregon Department of Transportation, might of thought at the time they were doing the right thing, but they weren’t. Tonight we need to be respectful of that negative and shameful history… It shouldn’t have happened.”

After that, the crowd took a visual tour of historical buildings on Williams Avenue with architectural historian Cathy Galbraith. Galbraith’s presentation, which also focused on the area’s many notable residents, gave people a sense of Williams Avenue’s history — a history marked with a vibrant street that bustled with Jazz clubs, markets, families, and black-owned businesses.

In 1943 alone, the population along the Williams corridor spiked from 2,000 to 23,000 people.

“When you make plans to change a neighborhood,” Galbraith said, “you have a responsibility to understand the history.”

Next up was Deborah Leopold Hutchins, the Chair of the project’s Stakeholder Advisory Committee (SAC).

Hutchins, who works for TriMet but doesn’t represent them on the committee, said “There might have been some mistakes in how the initial SAC was formed.”

Back in early May, it was Hutchins’ email to PBOT project staff that ultimately led to them to hit pause on the process. “Yes there are 4 people of color on a committee of 18 people,” wrote Hutchins, “That in and of itself makes for an unbalanced committee.” Hutchins’ fear was that the vote on a new street design (which took place just four days prior to her email being sent) was unfairly “swayed” by the 14 “white, regular bike riders, business owners and new implants residents as a result of gentrification” on the committee.

“We’re going to see what’s going to work best for the whole community, the Portland community, because as things stand now there is no ‘black community’ per se, as you look up and down Williams Avenue.”

— Gahlena Easterly, SAC member who moved to the neighborhood in 1942

Hutchins’ concerns were heard loud and clear. Not only has PBOT hit the pause button, they’ve added nine new SAC members (bringing the number to 27, twelve of whom are people of color), completely re-started the public process, and agreed to host this special community forum.

During her presentation Tuesday night, Hutchins praised the City’s decision to slow the process down and she read a list of new “guiding principles” that the SAC is due to adopt at their next meeting. These principles ask the City to “consider history, honor the legacy and respect the pain” that the community has experienced and to “critically evaluate” its public processes to make sure that “those with little power can be more actively engaged.”

Another committee member, Gahlena Easterly, shared a personal perspective on the street. Her words were measured and poignant. Easterly has lived in the area for 69 years and has seen its changes — mostly for the worse in her opinion — first-hand. She urged the crowd to understand that, “We’re having a conversation about a bicycle lane, but it’s more than that.”

area during the population boom in 1942.

As for the role of the committee, Easterly said, “We’re going to see what’s going to work best for the whole community, the Portland community, because as things stand now there is no ‘black community’ per se, as you look up and down Williams Avenue.”

The event continued with very brief presentations from three people representing active transportation: Steve Bozzone of the Willamette Pedestrian Coalition; Susan Peithman from the Bicycle Transportation Alliance, and former Community Cycling Center employee Mychal Tetteh.

Bozzone said that being able to safely walk across Williams is a “social justice issue” and that roadways should be designed with “the needs of pedestrians first.” He also shared statistics that illustrate the racial reality of traffic safety. When compared to whites, Bozzone said, black people are 73% more likely to die while walking across a street.

Peithman, also a SAC member, called the City’s past conduct in the Albina area “inexcusable” and that the project “must be done right” and “must have community support.”

Tetteh, who now works at a grocery store that serves the New Columbia neighborhood, spoke to the need for civility on the streets. “It’s the interaction between people that we’re trying to deal with… you can’t engineer solutions with stripes on the road.”

The second half of the meeting was spent in facilitated groups of 8-9 people. There were 17 groups and each one discussed several questions: What do you like and dislike about Williams? How can the city honor the street’s past? And if money was no object, what would be your dream for Williams?

The discussions were vigorous. People listened intently. Some laughed. Others aired annoyances, dreams, and personal stories. When the groups reported back, many different ideas got to be heard. More than one group mentioned the possibility of renaming Williams after a black leader. If money was no object, others said they’d build an African-American history museum or provide funds so that families displaced by gentrification could afford to move back to the neighborhood. Others said they’d spend the money on an elevated or underground bikeway.

Making N Rodney into the major north-south bikeway was an idea that several groups shared (we explored that back in August), as was moving the bike lane on Williams to the left side of the street. “No cars” was the dream of another group, while a few people advocated for some type of bicycle licensing scheme to raise money and curtail bad riding behaviors.

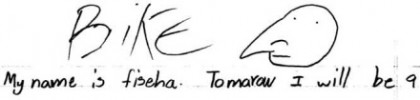

A nearly universal feeling was that the street, in its current form, feels unsafe and stressful for everyone… Including the youngest attendee, nine-year old Fiseha. He shared hand-written testimony and a drawing with PBOT staffers and I’ve shared it below:

My name is fiseha. Tomarow I will be 9. I live on morris st and go to Boise Eliot school. I would like to ride my bike to school and it’s very hard to go across williams st. I would like a safer way to bike or walk to school. I would like it to be safer to bike in my naber hood. Sometime I cant go to a place or to school on my bike. I have a one speed bike, but soon I will get a geer bike so I can go up hills like my mom and dad. But my mom said that I’ll get a geer bike in a loooooooong time.

Mayor Adams listened attentively to several of the group discussions. Afterwards he told me he was “really pleased” with what he heard. “I think people are realizing that there are human beings behind the headlines. They’re listening to each other.”

PBOT Director Tom Miller sat in with one group. After the meeting he told me he felt the meeting was “really productive and insightful.” “I was impressed that everyone came to the table with good intentions… People were focused on working collaboratively.”

“I heard strong consensus around speed reduction,” he said, “speed is at the core of what needs to be addressed.”

Miller feels this type of conversation is emblematic of a city that is “retrofitting from an auto-centric system to a truly multi-modal system.”

As for the tension and emotionally-charged issues surrounding the project, Miller said he’d rather focus on the “commonality” of what people want. Miller feels that fundamentally, everyone around the table wants a more “human-scaled, safe transportation system.”

“Last night reflects a growing consensus that we need better, safer, more predictable outcomes in the right of way… If we can get there, yesterday’s tension falls by the wayside… It’s our responsibility to provide that and we’re evolving our perspective… You can be a long-time resident, you can be a victim of the racism that the City exposed folks to, or you can be someone who is new to the area and rides a bike; but there’s a commonality of a desire for better, safer, more predictable interactions.”

“There’s a lot at stake here,” Miller continued, “This has evolved beyond a simple transportation project. I’m optimistic we’ll get to a good community outcome and the conversation on Williams could be an early sign of a new approach, a better approach, to public involvement.”

—

Stay tuned for more coverage on the Williams Avenue project. To learn more see our past coverage.