This guest post is by Michael Andersen of Portland Afoot, a “10-minute newsmagazine” and wiki about low-car life in Portland.

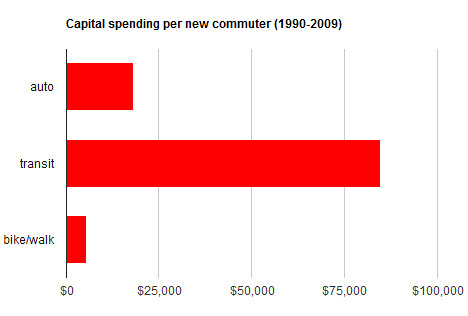

How much do various types of transportation projects cost taxpayers? Here’s an imperfect, but startling, hint:

From 1995 to 2010, our state and federal government spent $5,538 per new bike or foot commuter in the Portland metro area; $18,072 per new auto commuter; and $84,790 per new transit commuter.

(We don’t have 1995 commuting data, so this chart is based on new commuters from 1990 to 2009. If you’d rather compare 2000 and 2009, see my spreadsheet — story’s the same.)

“Is it worth spending money on transit? Yes, absolutely. Should we be spending money on bikes? Well, I think the data support it being a good investment.”

— Roger Geller, City of Portland

You’ve heard variations on this theme before, including my post last week about the arguments for and against a political bike-transit alliance. But you probably haven’t seen this particular comparison — it’s a variation on data first gathered by Portland Bicycle Coordinator Roger Geller. While working on last week’s post, I noticed that Geller had compared regional spending to City of Portland commuting trends, so I thought I’d see how things came out if you compared apples to apples: regional spending to regional commuting trends.

As you can see, things don’t come out well for public transit.

What’s more, the commuting data (from the 1990 Census long form and the Census’s 2009 American Community Survey) probably understates bike and pedestrian movement, because the Census asks people who use both bike and transit to list only the vehicle that carried them furthest, and only the one they used most frequently.

“If you only bike to work on days when it’s not raining in Portland … those trips aren’t even captured,” said Kelly Clifton, a researcher at the Oregon Transportation Research and Education Consortium (OTREC) and professor at PSU who keeps a close eye on local travel trends.

For its part, TriMet argues that commute statistics aren’t the best way to measure a transit system’s success. Unlike other transit agencies, TriMet’s philosophy is to transform the city into a place where cars are less necessary. This means no express buses or commuter rail lines, which are designed for once-a-day commutes from the suburbs to downtown, but lots of frequent service bus and MAX lines, which are designed for getting people to bars, ballgames and church services.

“The objective is not to fill trains with commuters (which represent only a fraction of all trips), but to provide alternatives to the automobile,” TriMet spokeswoman Mary Fetsch wrote Monday.

She’s got a point — when you look at overall transit ridership for a city of our size, TriMet is a top-of-the-chart success.

Still, as our country deals with a long-term decline in public services, it’s clear that TriMet’s successes have been very, very expensive.

Geller, who gathered the spending data, added that transit is, among other things, an important complement to bike transportation.

“If you don’t spend money on transit, then the bicycle is not a legitimate alternative for a lot of trips,” Geller said. “Is it worth spending money on transit? Yes, absolutely. Should we be spending money on bikes? Well, I think the data support it being a good investment.”

— The cover story of Portland Afoot’s April issue is about Portland employers with the best low-car commuting benefits. BikePortland readers in the metro area can subscribe for $10 a year with coupon code “bikeportland.” Email Michael at michael@portlandafoot.org.