“Public streets are for the movement of people, not long-term storage of vehicles.”

— from Bicycle Facilities for Portland: A Comprehensive Plan, 1974

A two-way cycle track at NE Glisan and 39th, a physically separated bikeway on SE 52nd, on-street parking removal to make room for bike traffic, painted crosswalks specifically for bikes (crossbikes?), a multi-use path along the Willamette River from Kelley Point Park south through the city and beyond — sounds like a wish list in the 2030 Bike Plan right? Actually, all of these things were dreamed up and suggested as priorities and policies in plans published nearly 40 years ago.

Last night, fledgling activist group Active Right of Way hosted their first Wonk Night event at the Central Library. The idea was to camp out in the reference room, dig up old plans, and let your inner transportation geek shine through. About an hour into the event, a corner of the otherwise subdued library was buzzing with energy. Maps draped across tables with four or five people hovering over them. Library staff worked double-time to keep up with all the requests.

And as for the old plans, we found some real gems. Below are just some of the highlights (I didn’t have room to detail 1917 toll rates on the Interstate Bridge or the Alder Street Train Station that would have been built in the 1920s in Waterfront Park)…

Spurred by the passage of the Oregon Bicycle Bill in 1971 (ORS 366.514, that mandated one percent of highway funds must be spent on biking and walking projects), visionary bike planners had high hopes that a new era for bicycles was about to begin. Two plans we found last night are symbols of that optimism and they show that over three decades ago bike planners were already considering many of the things we consider innovative today.

The first plan, A Bikeway Plan for the Columbia-Willamette Region, was published by the Columbia Region Association of Governments (CRAG, the precursor to Metro) in 1974. On one of the initial pages of that plan were the words, “An opportunity exists to implement a pedestrian and bicycle pathway network as one element of a balanced transportation system.” (And today, that opportunity still exists!)

The CRAG plan listed 86 bike projects and offered a suggested priority implementation schedule. I was amazed to find that their #1, top priority project was a trail similar to what citizen advocacy group NPGreenway is pushing for today.

The “North Willamette River Bicentennial Bikeway” was to be a demonstration project that would attract both commuters and the “recreational rider,” and would “illustrate what a high quality facility will do to stimulate further bicycling activity.” The proposed trail would start at Kelley Point Park and run south for 50 miles. To “focus public enthusiasm” on the nation’s 200th birthday, the trail was to be completed on July 4th, 1976.

The biggest gem we unearthed (in my opinion) last night was a plan titled Bicycle Facilities for Portland: A Comprehensive Plan. Published in 1973, this plan was prepared by the “Bicycle Paths Task Force,” which was a Portland-based, city-appointed group of citizens tasked with creating (what I think is) our very first bike master plan. (I assume this task force was the precursor to today’s City of Portland Bicycle Advisory Committee.)

An opening memo by Portland transportation commissioner Lloyd Anderson expressed deep gratitude for the task force’s work and shared these inspiring words:

“The resurgence of interest in bicycles… has some important implications for our system as a whole. The bicycle is no longer simply a child’s toy or excellent exercise, but is a prime mode of movement for many. The bicycle is low-cost, non-polluting, virtually silent, has minimal space requirements and consumes no fuel. These are important considerations at a time when the main form of transportation, the automobile, falls short on all of these.”

What was inside the plan was shocking (at least to us bike nerds).

Here’s what we surmised was a two-way cycle track treatment for the circle at 39th and Glisan:

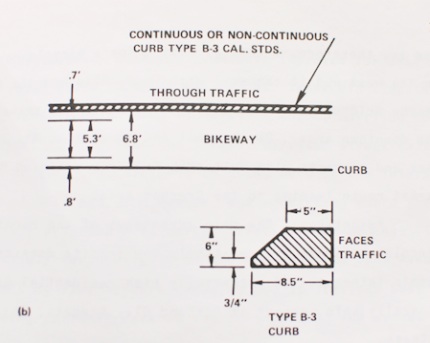

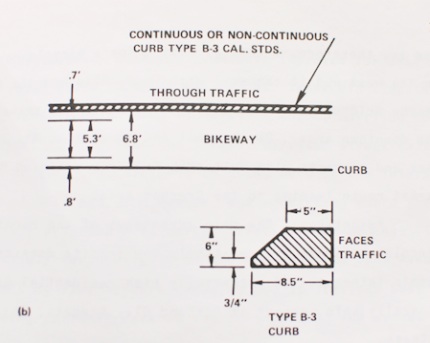

And a physically (via a curb) separated bikeway on SE 52nd from SE Lincoln to Francis that would come with removal of on-street car parking…

The next thing I read in this plan made me gasp. It was as if I was reading my own words; and to read it in something created 37 years ago was just fascinating. In a list of policy recommendations was the following,

“On streets designated as bicycle routes, on-street parking should be removed to provide exclusive bicycle lanes. Public streets are for the movement of people, not long-term storage of vehicles.“

The Bicycle Paths Task Force felt that providing separation between bike and car traffic should be a top priority. Their reasons were for safety, maximizing “street function” for mobility and not private storage, and they understood the connection between high-quality bikeways, a vibrant neighborhood and functioning local economy. In a section titled, “Rationale for Parking Removal,” they wrote:

“If people are encouraged to ride bicycles to shop… they will probably travel to the smaller stores near their homes rather than drive for miles to the large shopping center. The neighborhood stores… will be able to remain in business.”

I’ll be thinking of these passages when I watch people try to ride down Mississippi, Belmont, Alberta, and other commercial main streets where private cars park on both sides of a narrow street and people riding bicycles are forced to squeeze between them and car traffic.

Reading through these old plans was very illuminating. It helped me gain perspective on where we’ve been and where we’re at. I’m proud to know that bike advocates, city staffers, and political leaders throughout our region have clearly understood the benefits of urban biking for many decades. But on the other side of the coin, a part of me wonders why, if we’ve known what to do and how to do it for almost 40 years, why haven’t we been able to muster the political will to make it happen?

I wonder if some blogger 40 years from now will unearth the 2030 Bike Plan and share the same mixed feelings.