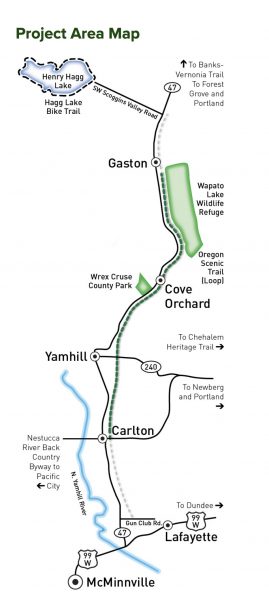

A rail-trail project in Yamhill County is moving forward with a planning process despite years of delays and disagreements about its impacts. The Yamhelas Westsider Trail — named after the Yamhelas tribe of the Kalapuya people who originally inhabited the land just east of the Coast Range and south of Forest Grove — is a 13-mile transportation corridor that will connect McMinnville to Gaston.

Thursday night an open house was held for the Yamhelas Westsider Trail Master Plan. That work, being led by Alta Planning and Design, will include a new project website, a robust public outreach process, and the creation of a project advisory committee.

The future path would be built on a 92-acre parcel of railroad right-of-way was abandoned in the 1980s after a century of use by Union Pacific. Yamhill County has recognized the corridor in its Comprehensive Plan since 2012 and purchased the land (with federal and state dollars) in 2016. In the past four years momentum for the project has gained steam as backers have won key state grants and the endorsement of Metro. But the project has also been met with severe opposition from landowners and farmers who live along the proposed route.

People against the path say it will harm farming practices, lead to humans and dogs trespassing on sensitive crops, result in lawsuits and protests about the use of pesticides, encourage illegal camping, and so on. In June 2020, the Capital Press, a news outlet that focuses on agricultural issues, said the County should cancel the project.

Advertisement

Recent progress is also under threat due to a new anti-project majority on the Yamhill County Commission. The project’s biggest backer, Commissioner Casey Kulla, used to enjoy a 2-1 voting block of support. But with Commissioner Rick Olson leaving the commission next month, Kulla will now be in the minority.

According to the Yamhill County News-Register, “Commissioner Mary Starrett has opposed the trail, as has incoming Commissioner Lindsay Berschauer, who made her opposition a plank in her election campaign and received funding from trail opponents. The two, with a new majority, could scuttle the trail’s development.”

For now the project is still very much alive, but legal challenges and a pending decision from the Oregon Land Use Board of Appeals has led to delays.

“Folks out here have a hard time finding spaces open to them that are safe,”

— Casey Kulla, commissioner

Project supporters hope compromises are possible (even a different alignment isn’t off the table) and say none of the concerns raised by landowners are insurmountable. They also say the benefits of a safe transportation corridor that will help keep people off of dangerous Highway 47, provide options to driving, and help stimulate the local economy, far outweigh any risks.

Wayne Wiebke, president of the nonprofit Friends of the Yamhelas Westsider Trail, wrote to ODOT’s Bicycle and Pedestrian Advisory Committee last month urging them to help keep the project moving forward. “Currently there is no safe north-south route for pedestrians and bicycles through Yamhill County,” Wiebke wrote. “This puts our students in the Yamhill Carlton School District at risk, as children go to elementary school in Carlton and middle and high school in Yamhill, with no safe route between the cities.”

The Friends added in a email to BikePortland today that they were “humbled” by the dozens of supporters who attended last night’s open house. But there joy was tempered by the reality that, “progress may be stymied in the near future” due to the political shift on the Commission. “To keep momentum and hope alive for this project, it will be critical for supporters of the trail to speak up and show how much the majority of the community wants this project for the safety and health of our families and communities.”

Advertisement

Commissioner Casey Kulla will need this support. He told me in an interview yesterday that a carfree path is vital for his constituents. The idea of having lots of room to move around safely in rural areas is a “myth”. “Folks out here have a hard time finding spaces open to them that are safe,” Kulla said, standing in a field on his family’s vegetable farm. “Public spaces on rural roads are intended for cars or farm traffic and knowing you are safe from those obstacles is very attractive to many people.”

Kulla is “completely optimistic”. He thinks the project should bring people together and is “saddened” the division around it. If no deal can be struck with those in opposition to the project, Kulla says it could be stalled until new commission elections are held in two years.