It’s not 2008. But for the first time in seven years, Portland’s bike believers seem to have the wind at their back.

The latest evidence showed up Thursday in new Census Bureau estimates showing that 2014 brought the city to its highest bike-commuting rate on record: 7.2 percent.

The change falls slightly inside the statistical margin of error, so there’s something like a 5 percent chance that the increase is just a statistical anomaly. That said, it’s enough to end a five-year plateau in the city’s estimated bike-commuting rate.

According to the Census, Portland had 23,347 bike commuters last year, give or take about 3,000. That’s a 27 percent jump over the previous year’s estimate of 18,337.

Out of the approximately 14,000 additional commutes by Portland’s workforce last year, about 5,000 happened on bikes.

As biking rates rise, car commuting rates fall

There’s more good news, including for people who drive to work: if this year’s numbers stick around, the growth in biking will correspond to a similar drop in car commuting.

Compared to the 2009-2013 average, Portland’s drive-alone rate edged down from 59 percent to 57.6 percent.

That comes out to 1,900 drive-alone commutes that would be on the road today if not for the shift away from driving and toward biking.

This doesn’t mean that Portland’s streets aren’t getting more congested. They are. Because of job and population growth, Portlanders added 9,000 more drive-alone commutes to the road last year. As we reported last month, Portland will have to do far better than it is currently doing if it’s going to repeat its trick of the 2000s and add jobs without adding congestion.

Advertisement

This brings us to the bad news. Except for biking, low-car commute options haven’t been getting more popular among Portlanders.

Carpooling, though stable recently, has been on a decades-long slide. Walk commuting posted a big jump in 2012 that turns out to have been a blip. Public transit use is also flat, despite a big effort by TriMet to restore bus service that was cut during the recession.

Working at home is edging up, but not rapidly.

For other leading cities, the stall continues

Nationally, bike commuting rates didn’t budge in 2014. The country added 22,000 new bike commuters — but after accounting for growth in the working population, the overall rate stayed flat at 0.62 percent.

In other major biking cities, the news was mixed.

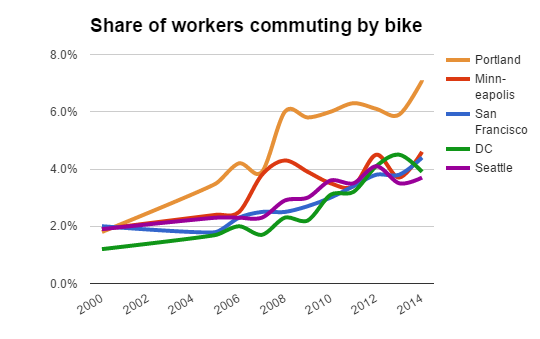

Outside of Portland, some of the best news in today’s Census report comes from San Francisco. After big investments in its bike lane network, that city continues its upward trajectory and just hit 4.4 percent biking, a modern high.

Minneapolis rebounded to 4.6 percent, making a possible slip last year look more like a continued plateau. Seattle’s five-year plateau continues; it saw a 3.7 percent biking rate. New York City, at 1.1 percent, seems to be settling into a post-Bloomberg plateau of its own.

Washington D.C., which doubled its estimated bike-commute rate from 2009 to 2013, slipped back to 3.9 percent after several years of minimal investments by its leaders. Los Angeles, Chicago, Boston, Oakland and Tucson all hit new highs.

The limitations of Census data

The Census measures only journeys to work. It doesn’t include the commutes of full-time students, or travel by people who don’t have jobs. It ignores errands and social or recreational trips, which are about 80 percent of the trips Americans take.

It’s based on a survey, conducted on a rolling basis throughout the year, that asks people the main mode they used to get to work most days last week. If someone uses two modes — driving to a train station, for example — it counts only the one that carried them the most miles.

Despite all of those limitations, the Census is the single most reliable and useful way to measure how a city is doing on biking. Because people are legally required to answer its surveys — a mandate that Republicans in Congress are currently pushing to remove — it has high response rates and low margins of error.

Unlike Portland’s manual bike counts, the Census includes people who work nontraditional shifts — an important biking constituency because the two professions most likely to bike-commute are food-service workers and college educators.

What caused Portland’s latest bike spike?

This new leap in Portland’s estimated bike commuting sets a modern record for the city and the highest bike-commuting rate ever recorded for a U.S. city of more than 200,000 residents.

(In fact, it means that Portland’s bike-commuting rate has exceeded Eugene’s for the first time ever; that city came in at 6.8 percent. Numbers for Corvallis, Oregon’s longtime No. 1 bike-commute city, aren’t out yet.)

What could have caused this jump?

Assuming the figure doesn’t turn out to be a one-year blip — and it might — here are our three top theories.

1) Workforce turnover. It’s important to remember, when we talk about 5,000 of Portland’s additional 14,000 commutes happening on bikes, that we’re talking about both old and new residents. Ten to 20 percent of Portland’s population churns in and out of the city every few years, and people are constantly switching from one mode to another as their life circumstances change. An increase like this is probably driven in part by a natural progression of less bike-oriented people leaving the Portland workforce.

2) Infill apartments. Love them or hate them, Portland issued 5,000 new multifamily building permits in 2012 and 2013, and the boom continues. These apartments, which are almost all being built with far more bike parking than auto parking, account for about three-quarters of all the new homes in Portland in the last few years.

Here’s a strong clue that rising density is changing Portland’s commute habits: people who live in Portland’s suburbs didn’t see a bike spike. Vancouver, Hillsboro, Beaverton and Gresham all have bike-commute rates around 1 percent, which is pretty good by suburban standards. But essentially all of the biking growth in the metro area last year — both over the 2009-2013 average, and over the one-year estimates from 2013 — came from Portland residents.

3) Neighborhood greenways. The bike lanes Portland painted in the 1990s took a few years to pay off. Our network of bike-friendly side streets, mostly installed from 2010 to 2012, may have done the same. I’ve been a skeptic about the ability of neighborhood greenways to lure people out of cars, because I think the network isn’t very intuitive to new users. But that doesn’t mean neighborhood greenways aren’t awesome. They are — especially for commuting. Hopefully I’m totally wrong about their shortcomings.

There are surely other factors at play. We’re eager to hear your thoughts.

Finally, a word of caution: something very important happened at the end of 2014, just as this survey was wrapping up. Gas prices plummeted, and have basically stayed low since.

This year, the drop in gas prices has combined with the decent economy (especially here in Portland) to create a national rebound in driving. It’d be shocking if that isn’t happening in Portland, too.

Today’s news makes Portland, at least for the moment, one of the brightest stars in the national biking movement once again. Harder days for that movement may lie ahead. Let’s savor this achievement — and keep our eyes on the horizon.

Correction 10 am: An earlier version of this post misstated the bike commuting increase in Detroit.