(Photos: J.Maus/BikePortland)

As Portland edges closer to possibly adding protected bike lanes to its downtown, a new study has found that one of its most unusual bike-lane intersection treatments seems to be working.

The LED sign above the intersection at NE Couch and Grand that flashes “Turning Vehicle Yield to Bikes” seems to have reduced right-turn conflicts by more than 60 percent since its 2011 installation.

However, the design hasn’t eliminated injuries or conflicts — an engineering term that refers to braking or changes of direction to avoid a collision — in the way that a dedicated bike signal phase might be expected to.

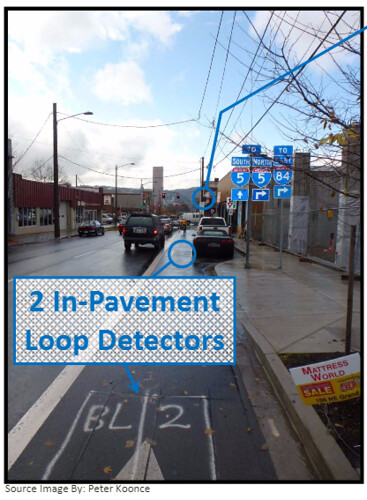

Here’s how the sign, the only one of its kind in the United States, works: there’s an inductive bike detector loop in the pavement in the bike lane just east of the intersection…

…and when it’s triggered, it causes the LED sign across the intersection to flash, hopefully reminding people in cars that they need to yield to a bike overtaking them on the right before making their right turn.

Many Portlanders weren’t big fans of the sign when it was installed. One of them was Kirk Paulsen, an analyst for Lancaster Engineering who worked on the new city-funded study.

“Before going into the data, I was skeptical of the effectiveness and thought it would be viewed as more of a neon advertising sign, and was surprised that it was shown to be as effective as it was,” Paulsen said in an interview Wednesday.

Advertisement

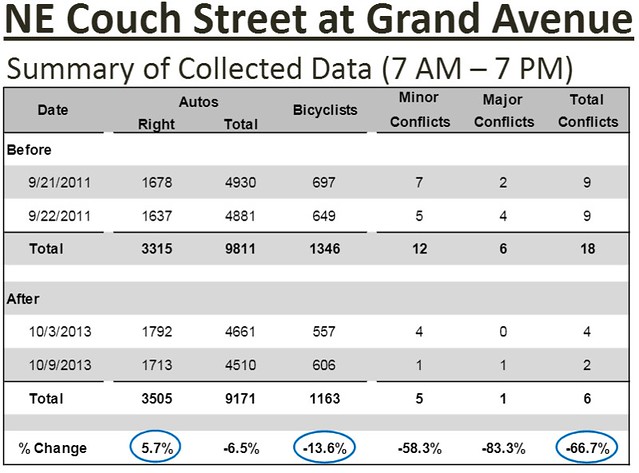

But after analyzing 24 hours of daytime video footage from before and after the sign was installed — 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. on two days in late September 2011, compared to the same times on two days in early October 2013 — Lancaster’s analysis found that the number of turning conflicts had fallen 66.7 percent:

After adjusting for different numbers of conflicts per right turn and per bicycle, the results came out even better. “Major” conflicts, categorized as those that required substantial braking or course adjustments by one or both vehicles, plummeted more than 80 percent after the sign’s installation. Total conflicts fell 68.5 percent per right turn and 61.4 percent per bicycle.

“Based on the research it’s a really strong benefit,” said Peter Koonce, manager of the city’s signs and signals division.

Based on these findings, Koonce said the sign — which isn’t in any official federal manual of traffic signs — is on the table as an option for the coming upgrade to downtown biking and walking facilities.

“One of the next steps that we’ve contemplated was studying Broadway and Hoyt, which is a notoriously bad location,” Koonce said. “That sign is a viable option for Broadway and Hoyt.”

But Koonce also sounded notes of caution, saying that he too isn’t sure the LED sign will work elsewhere.

“I worry that it’s just noise, and that this is just one study,” he said. “It’s like the Food and Drug Administration, right? Your results may vary. … The takeaway that I hope we can share is that we’re going to be looking at these things.”

Several other factors are at play. At the time of the 2011 video footage, the bike box there was only one year old, and its effects on behavior, if any, might still have been developing. Also, there’s no scholarly consensus about whether reducing the number of conflicts between cars and bikes reduces the number of crashes.

However, Lancaster’s analysis also looked at the number of serious collisions at the location that were reported to authorities and/or BikePortland in the year before the sign’s installation and the two years after. Then they used their video statistics and Hawthorne Bridge bike traffic trends to estimate the number of bikes that came through the intersection during those periods. Using that method, the number of known serious collisions fell from three per year to two per year.

Those figures are far from definitive, though, because bike-related collisions go unreported.

Moreover, the estimated number of people observed on video biking through the intersection declined slightly from 2011 to 2013, a change that might be weather-related but suggests that despite the drop in conflicts, users didn’t find the new design significantly more comfortable or otherwise appealing.

Footage of a December 2013 right-hook collision, captured by a TriMet bus. The victim received upper and lower back injuries that required months of physical therapy and prevented use of his bike for transportation.

And Koonce noted that according to these findings, the LED sign failed to eliminate crashes. The city says it aims to completely eliminate traffic fatalities and serious injuries.

“Does a sign do that?” Koonce said. “No, a sign wouldn’t give you zero. But a signal probably would.”

On the other hand, Koonce said, using a dedicated bike signal to reduce right-turn conflicts can also increase traffic delay for all users. In some situations, like the one at Broadway and Hoyt, it might also require a general travel lane to be converted to a dedicated right-turn lane, because the rightmost lane with car traffic couldn’t simply display a green light.

Another downside of a dedicated bike signal phase, Koonce said: if it doesn’t offer a clear safety benefit, some people might not comply with it while riding bikes.

— Portland has tried many different approaches to dealing with right-hooks over the years. Learn more by browsing our right-hook story archives.

Correction 4/3: An earlier version of this post incorrectly described the loop detectors.