What if talking on a cell phone behind the wheel isn’t so dangerous after all?

What if people who are on the phone naturally tend to drive more carefully, essentially canceling out any danger?

That’s the startling implication of a cleverly designed study released Thursday that hasn’t yet gotten much attention in the media. Its authors, a professor of social and decision sciences and an economist, readily admit that their findings seem contrary to some (though not all) previous work in the area.

But if there are obvious flaws in this fascinating bit of research on a question that matters to everyone on the road, I don’t see them — and we’d love to give BikePortland readers the first chance to find them.

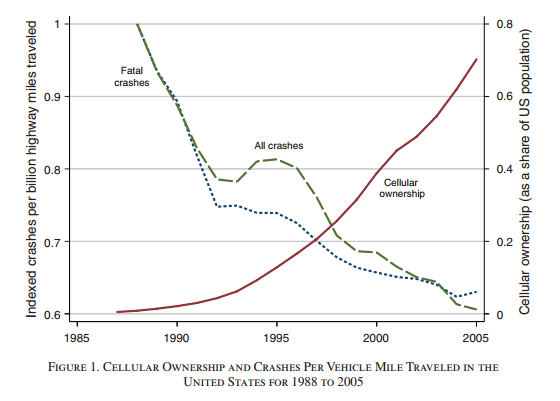

The authors, Saurabh Bhargava of Carnegie Mellon University and Vikram S. Pathania of the London School of Economics, start their paper with a big puzzle: If talking on a cell phone is as distracting as being drunk, and cell phone use has been increasing rapidly for 30 years, why have U.S. highways been getting so much safer?

rapidly rarer, though cell phone use is increasing.

(Images by Bhargava and Pathania)

Today, the authors write, the average cell phone user talks for 740 minutes a month, and surveys show that “as many as 81 percent of cellular owners use their phones while driving.” If the most influential previous study on this subject is right, this ought to be a disaster for U.S. roads.

That influential study, a 1997 paper that examined the phone bills of Canadians involved in car crashes, concluded that people in cars are 4.3 times more likely to crash while using their phones. That research, plus the common intuition (mine included) that talking on a phone is distracting, has helped lead 37 states (including Oregon) to forbid or restrict the practice.

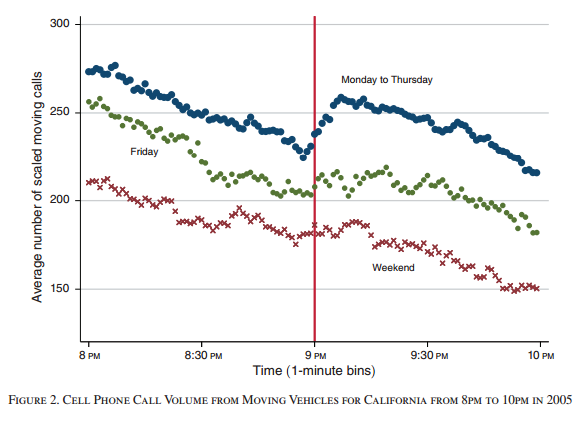

Bhargava and Pathania raise several problems with the 1997 study, one of which is that its authors may not have accounted properly for the chance that people are more likely to place calls immediately after a car crash. Then, they bring out their most interesting insight: from 2002 to 2005, there was a big spike in cell phone usage every weeknight at 9 p.m., when millions of Americans switched to nights-and-weekends minutes.

by 7 percent right after 9 p.m. on weeknights.

Even more impressive, the authors convinced an unnamed cell phone company — a source that, it’s worth noting, isn’t exactly disinterested on this subject — to share data specifically from phones that were rapidly switching from one cell tower to another, so fast that they must have been in a moving vehicle. That’s the data in the chart just above.

If cell use greatly increases the chance of a crash, the authors conclude, you’d expect crash rates to spike at 9 p.m, too. But they didn’t:

The authors write that they don’t think hands-free phones were an issue: those were uncommon before 2005, and in any case research shows that they’re just as distracting as regular phones.

Instead of disputing the fact that talking on a cell phone tends to be distracting, Bhargava and Pathania suggest three theories:

“It is possible that drivers who use such devices compensate for the added distraction by driving more carefully. Alternatively, it could be that risk-loving drivers may treat cell phones as a substitute for other, equally debilitating, distractions. Finally, because we measure a local average treatment effect, it could be that cell phones are dangerous for certain drivers (or driving conditions) and are beneficial for others, or that our estimates reflect an unrepresentative time of day, mix of drivers, or composition of calls.”

It’s a provocative paper, no question. And it seems likely to get more attention in the media. What’s your take?