for many, things change in their teens.

Image © J. Maus/BikePortland

Statistically speaking, girls and boys tend to have similar attitudes toward bikes until their 14th birthday or so. But around that age, gender attitudes diverge dramatically – and no one’s quite sure why.

As they enter puberty, Portland girls suddenly start reporting much more concern about not knowing “how to exercise the right way,” according to a new study. That’s also the age at which girls start worrying more than boys do about hurting themselves if they’re physically active.

Portland State University researcher Tara Goddard, who presented those findings to colleagues Friday, wonders if girls and boys should get different sorts of encouragement as they build active teen lifestyles.

“Maybe we need to catch them before this split starts to happen,” Goddard said Friday. “Otherwise you’re kind of working backwards and trying to repair that split.”

Boys who turn 14 may still worry about the same issues, Goddard’s research shows, but it tends to be at the same rates they did when they were younger.

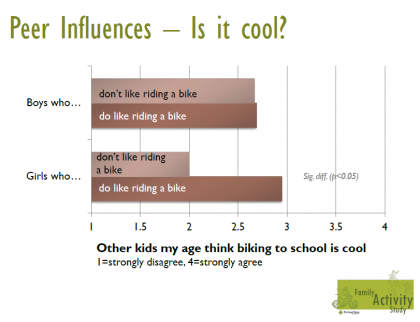

Another big divide between girls and boys relates to their attitudes toward their peers. Whether or not boys ride bikes themselves, they feel about the same way about whether other kids their age ride bikes for transportation and whether biking to school is “cool.”

But girls who like bikes are much more likely than girls who don’t like bikes to say their peers think highly of bicycles.

“By age 14, girls are embarrassed to be seen exercising,” Goddard said – and girls who feel that embarrassment more are much less likely to ride bicycles. “Do girls think of bicycling as a non-trivial physical activity?” Goddard wondered. “Or you could look at it the other direction: do girls who like bicycling have this body confidence and they’re more comfortable being seen exercising?”

Goddard has looked into different programs designed to attract teens to biking. She found that public health programs tend to be more about discouraging unhealthy behavior – stopping smoking, for example – than encouraging healthy behavior.

She also said it’s hard to find programs targeted directly toward helping girls build social connections with peers who ride bikes.

“A lot of girls are more likely to report the influence of their peers, so can we take advantage of that to be able to leverage the influence of bicycling as a transportation mode?” Goddard asked.

Bike-fun groups like Portland’s Sprockettes, who recently started operating a summer bike-dance camp for girls, do come to mind. I also thought about this amazing video from a group of young Minneapolis rappers, both boys and girls, about their love of bikes.

This gender split among tweens is one tantalizing drip from a geyser of new data about to emerge from a three-year, $400,000 study of 323 Portland households’ travel behavior. The study was funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, OTREC and the City of Portland, and it promises a huge amount of new data on how families who live in different neighborhoods navigate our moderately multimodal American city.

“This is just the very first cut – the exploratory stuff,” Goddard said. “During the next six months to a year to 18 months, there’s going to be a lot of cool stuff coming out on this project.”