Seattle resident Jan Heine is a very respected figure in the bicycling world. As editor of Bicycle Quarterly, a magazine that delves deeply into bicycle design and randonneuring, he has a large and loyal following. So when he published a lengthy blog post yesterday that was highly critical of the “worrisome trend” in the U.S. of building and advocating for cycle tracks and other types of physically separated bikeways — I wasn’t surprised at the heated debate it stirred up (both in his comment section and on Twitter when I shared the link).

Heine has touched a nerve on one of the the most heated debates in the bicycling world: Should we create separation (which is the outlook held by almost every major bike advocacy organization) similar to the great bike cities of northern Europe; or should we focus on educating people how to “take the lane” and maintain the push for “vehicular cycling” wherein people on bikes learn to share lanes with those of us in cars. (Or better yet, as some have pointed out in comments below, we should combine the best aspects of the two approaches.)

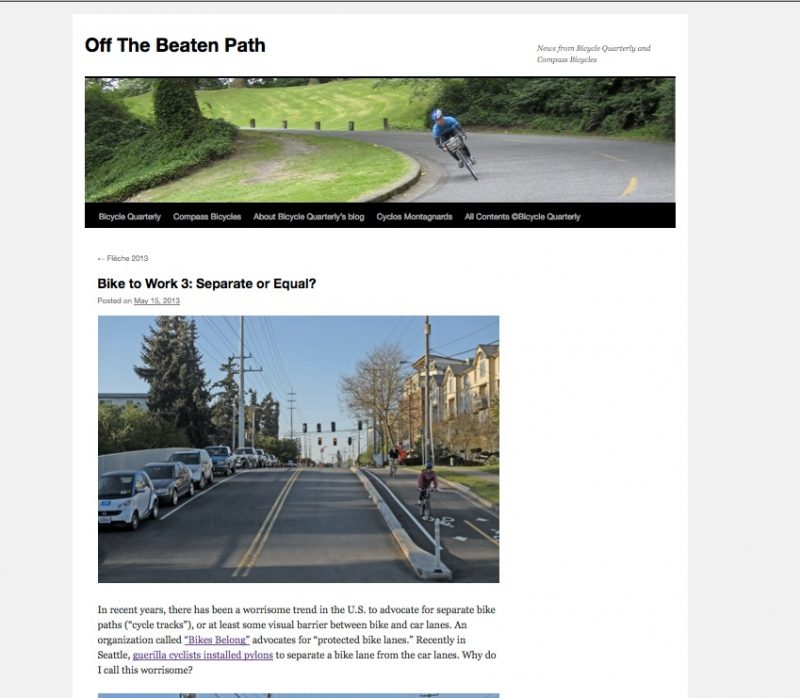

In his blog post, he explains his position in thorough detail and several photographs of a protected bike lane (I’m not sure of its location, but it’s clearly in the U.S.). Here are a few excerpts (which I share with concern for lack of context and I recommend reading his entire post):

“At first sight, separate bike paths seem appealing. You are away from cars, riding by yourself…

Unfortunately, this idyllic view hides some very real dangers.

To understand bicycle safety, it is important to look at the actual, rather than perceived, dangers. The danger of being hit from behind or being “clipped” by a car passing too close is very small. It accounts for less than 5% of car-bike accidents.

Most accidents involving bikes and cars occur at intersections…

This is the greatest danger for cyclists: being overlooked in traffic. Since drivers usually scan the road for cars, cyclists are safest if they ride where drivers look for cars. To be safe, cyclists must be an equal part of traffic.

Heine’s greatest concern is one shared by a lot of critics of separated bikeways: that they decrease visibility, lead to more collisions, erode riders’ right to the road, and lead to a false sense of security.

Pointing to data from Berlin, Heine is convinced that separated bikeways lead to more collisions: “On streets with frequent intersections, separate paths only make cycling less safe. I wish those who advocate for them would look at the data and stop asking for facilities that will cause more accidents.”

If separated bikeways are so bad, why do they exist in all of the best biking cities in the world? Here’s how he explains that:

“Having lived in Europe, I believe that cycling there is successful in spite of (and not because of) the bike paths. It may help to know that separate bike paths originally were not introduced to make cycling better, but to clear the road for cars (by the car-obsessed Nazis in Germany). For that reason, cyclists were required by law to use the bike path, whether it was well-designed or not. Other European countries quickly followed this “innovation.” It spread to yet more countries when Germany invaded much of Europe during World War II.”

Heine’s post has garnered a lot of support and a lot of opposition with strong feelings on both sides. It shows that, while separated bikeways have come to dominate the U.S. bike advocacy vision — there remains support for a more vehicular cycling approach.

The League of American Bicyclists knows this all too well. After years of internecine wrangling within their board, ardent vehicular cycling advocates only recently realized the League would never stray from a promotion of separated facilities. Given that, they’ve moved on and have created IAmTraffic.org to promote their vision.

While I know many people disagree strongly with Heine’s perspective, I think it’s important for advocates and activists to realize, acknowledge, and respect it. Is there a way to meld these visions? Or is this battle of perspectives destined to persist? Will promotion of separated facilities lead to a loss of “rights to the road” for people on bicycles?

Read Jan Heine’s post: Bike to Work 3: Separate or Equal?.