(Photo: J. Maus/BikePortland)

Yesterday the Portland Bureau of Transportation released the final report of their East Portland Arterial Streets Strategy (EPASS). This marks a key final step to an effort we reported on when it started back in late 2018.

A goal of EPASS is to inform advocates, community members, policymakers, leaders, and even PBOT staff themselves, about how best to move forward in taming east Portland’s notorious arterials.

East Portland is home to about a quarter of the city’s residents, yet suffers over half the traffic deaths. Underlying this disproportionate statistic is the fact that 28 of the city’s 30 high crash intersections sit east of 82nd Avenue.

“People have urged us to make sure we’re considering our streets as a system, not just making changes in a vacuum on each street.”

— Chris Warner, PBOT Director

The EPASS study, which covers 42 miles of the east Portland arterial network and runs 68 pages long with 10 technical appendices, has several objectives. One, it seeks to better understand the cumulative, system-wide effects of the numerous capitol projects planned, underway or completed in east Portland. As PBOT looks to make significant changes to street designs, EPASS addresses the public’s concerns around the question of “What will happen to traffic patterns when we change multiple streets in the same area?”

It also attempts to communicate with the public the process, safety findings, and best-practice interventions that have guided PBOT toward “the most appropriate and effective tools to reduce crashes while making sure people can still get to their jobs, schools and other destinations on time, whether by walking, biking, taking transit, or driving.”

Advertisement

And tucked in toward the end, the report also states that it is “decision documentation for PBOT staff as we move forward with implementation of projects and programs.” In other words, it also serves as internal documentation of the overall strategy and goals for the area, and how individual projects fit into them.

During the height of the Covid shutdown, traffic decreased by 60% in the central city, but it only decreased by 30% in East Portland.

The importance of a coordinating document like this should not be underestimated, especially in an area like east Portland which is benefitting from over $200 million in safety projects under several different programs, including Vision Zero, Neighborhood Greenways, Transportation Demand Management and the East Portland Action Plan. The EPASS report should help keep everyone on the same page — PBOT staff, neighborhood advocates, the community, even curious media like us. It can be viewed as a meta-document for the area and a resource for basic facts and project history.

The report recommends new lane configurations (reducing the number of travel lanes) on a third of the arterials they studied. This accommodates more or better protected bike lanes, pedestrian islands, center turn lanes, and bus-only traffic. The EPASS project website has a video which explains that traffic signals at intersections are the “pinchpoints,” which is why road diets will not significantly increase travel times. The Corridor Summaries Guide section of the report has a two-page summary of vital stats for each of the 11 corridors analyzed (above) and it shows recommended street cross-sections. This alone will be a useful resource. Currently there are 15 funded safety projects underway and PBOT is seeking funding for an additional nine projects.

There were a few findings in the report that caught my eye. During the height of the Covid shutdown, traffic decreased by 60% in the central city, but it only decreased by 30% in East Portland. This is consistent with the bifurcation of Americans into “essential” workers who had to show up to their jobs working the register, delivering food, treating patients, providing care, keeping the community safe, and those of us who work can work from a home computer. The difference also speaks to the different land-use patterns and safety of infrastructure for non-driving trips. The natural experiment provided by the pandemic has helped PBOT model what travel will look like in the future and has led the bureau to predict that east Portland will continue to be car-dependent relative to inner-Portland neighborhoods.

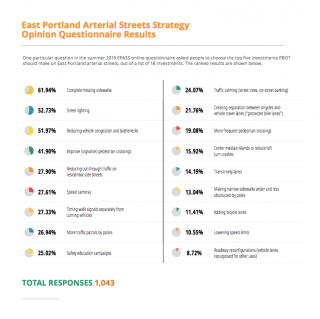

Also, only 22% of respondents to a 2019 online survey shared in the report (above, right) considered protected bike lanes to be a priority investment, and only 11% prioritized adding new bike lanes. And scoring last, at a little under 9%, the public really did not see road diets favorably. It was interesting to notice that, despite the survey findings, new bike lanes or better-protected bike lanes were part of the proposed cross-sections of all of the corridors studied.

— Lisa Caballero, lisacaballero853@gmail.com

— Get our headlines delivered to your inbox.

— Support this independent community media outlet with a one-time contribution or monthly subscription.