(Photos: Jonathan Maus)

Portland has been talking about physically protected bike lanes for years. The problem is, we’ve mostly just been talking — and not building. And when we have built them, the designs have been inconsistent.

One of the (many) reasons for the slow implementation of protected bike lanes is that engineers, planners, and project managers at the Portland Bureau of Transportation haven’t been reading from the same book. In fact, they haven’t even had a book. Until now.

Last week PBOT’s bicycle program manager Roger Geller shared a sneak peek at a new manual that will soon be adopted as the official Portland Protected Bicycle Lane Design Guide.

“We’re going to start with a protected bike lane and you better have a really good reason why can’t do it.”

— Roger Geller, PBOT

“It provides much-needed clarity about what we can build and how it will fit on Portland streets,” Geller told an audience of several dozen (mostly planning students) at a “Lunch and Learn” event hosted by PBOT at Portland State University last Thursday. Geller said the guide came about in large part because outgoing PBOT Director Leah Treat issued an internal agency directive in 2015 that called on staff to make protected bike lanes the default whenever possible. “That directive kind of flipped things on its head for our agency,” Geller explained. In the past they would start from a standard, six-foot bike lane and work up toward protection. Now, Geller said, the approach is different: “We’re going to start with a protected bike lane and you better have a really good reason why can’t do it.”

Treat’s memo was just one part of the impetus for this guide. Geller also shared that it was born from a struggle by PBOT engineers to come up with designs. “Our first five protected bikeways were all different designs,” he explained. “We’d sit down and say, ‘What should we do?’ And Engineer A says, ‘I know, let’s do this.’ Then another street would come up, and we’d say, ‘What should we do for this one?’ And it would be a completely different design.” “The first five were all one-offs,” he continued. “At a certain point our engineers were begging for mercy, saying, ‘Give us some tools!’ The existing guidebooks weren’t sufficient.”

(Click images for gallery and captions. ESC to return to post.)

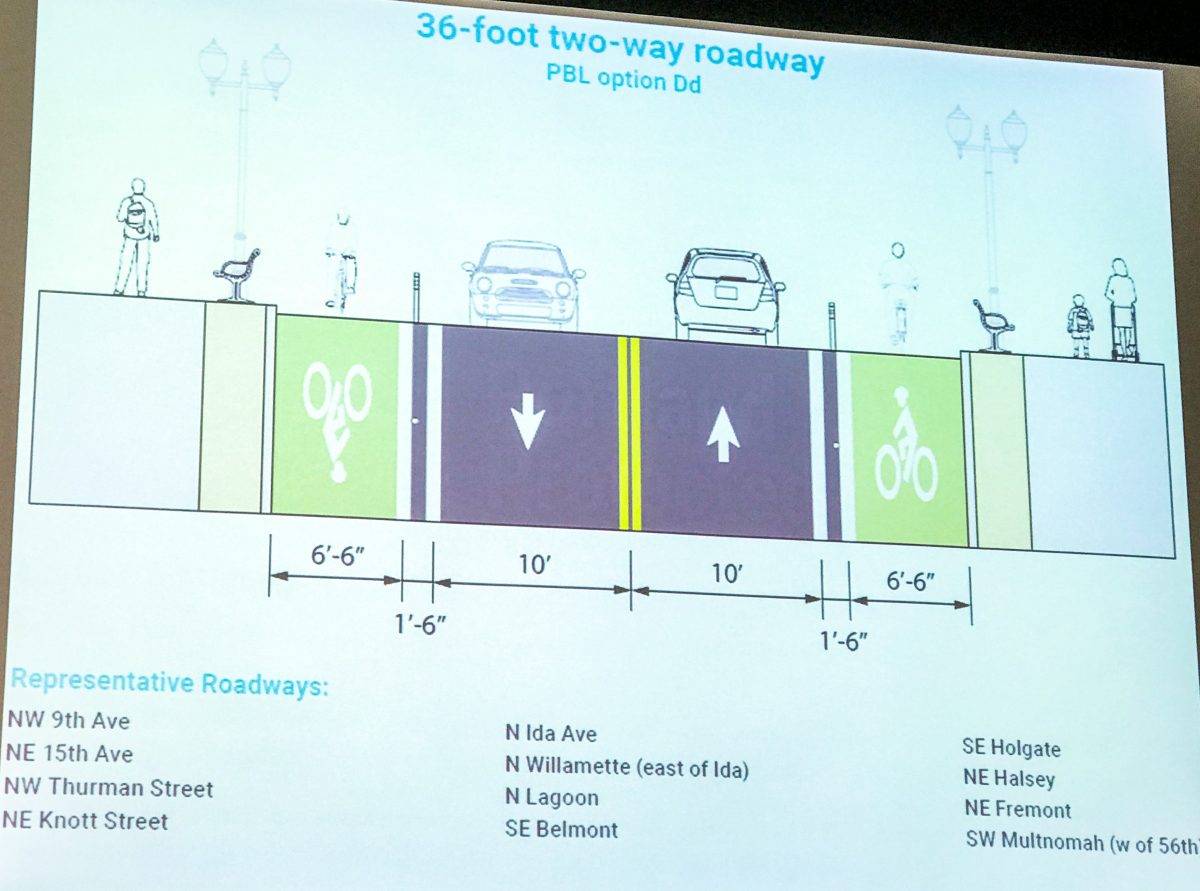

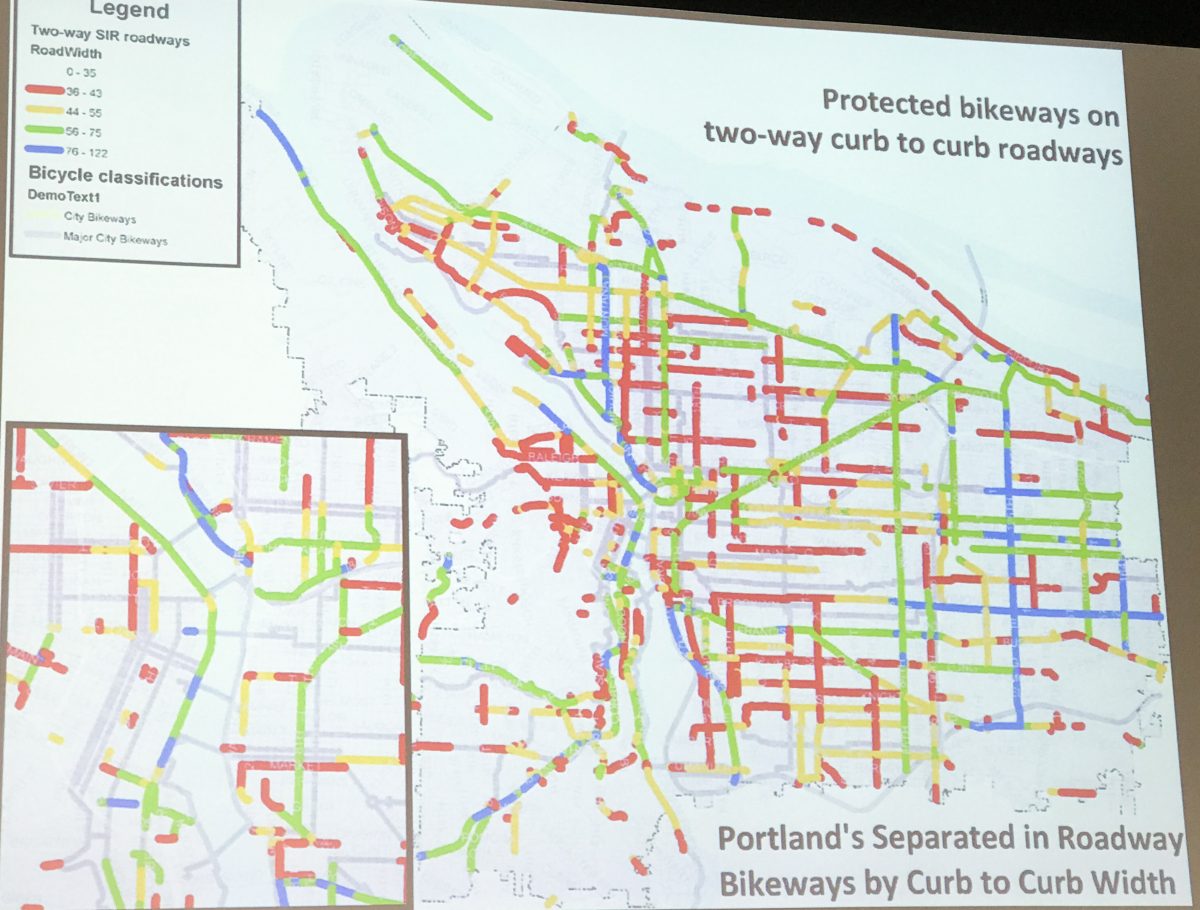

The bulk of the guide lays out different street cross-sections and suggests seven basic designs. This is meant to help city staff determine what’s possible given nearly any street configuration they come across — from a 76-foot wide, two way road to a 44-foot one-way road. The final guide will include an online spreadsheet tool that will allow engineers and project managers to plug in a specific cross-section and receive design ideas that will fit.

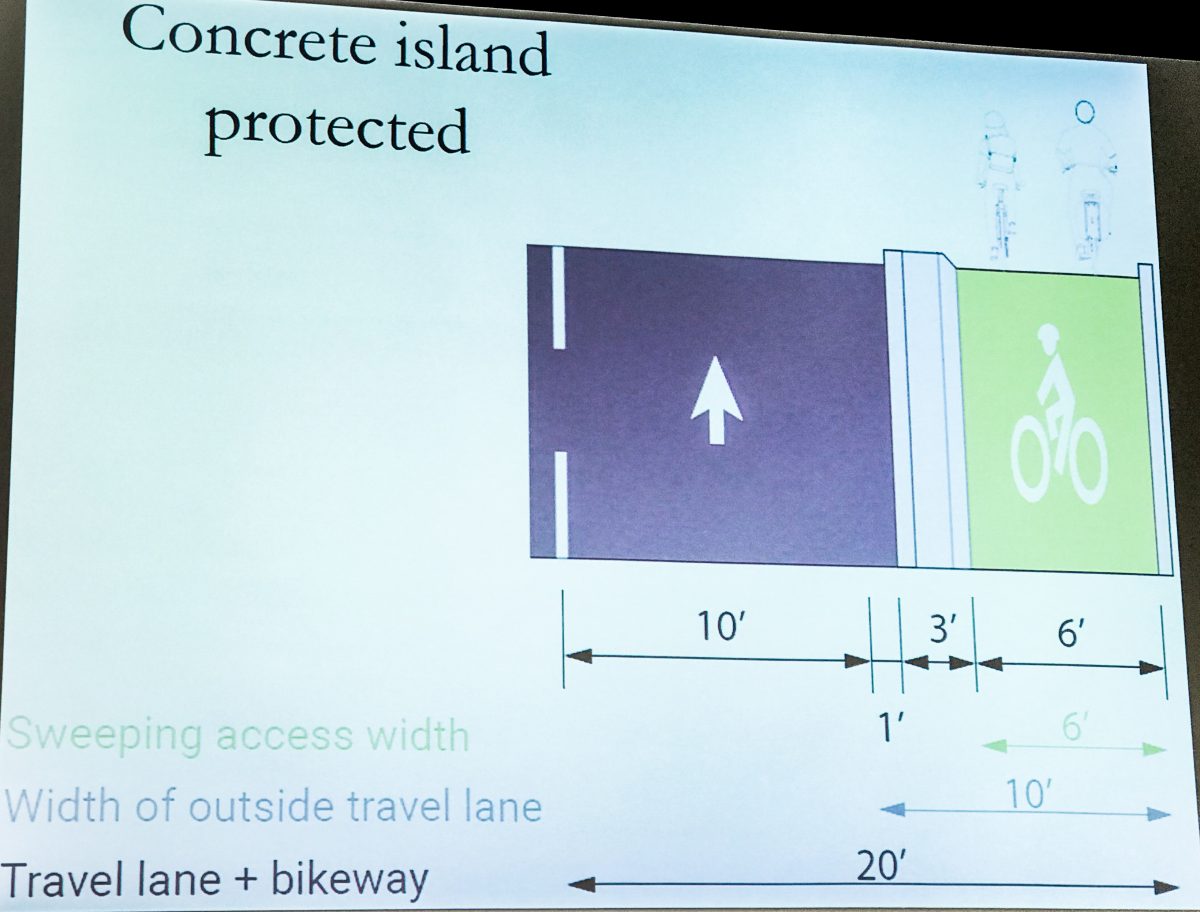

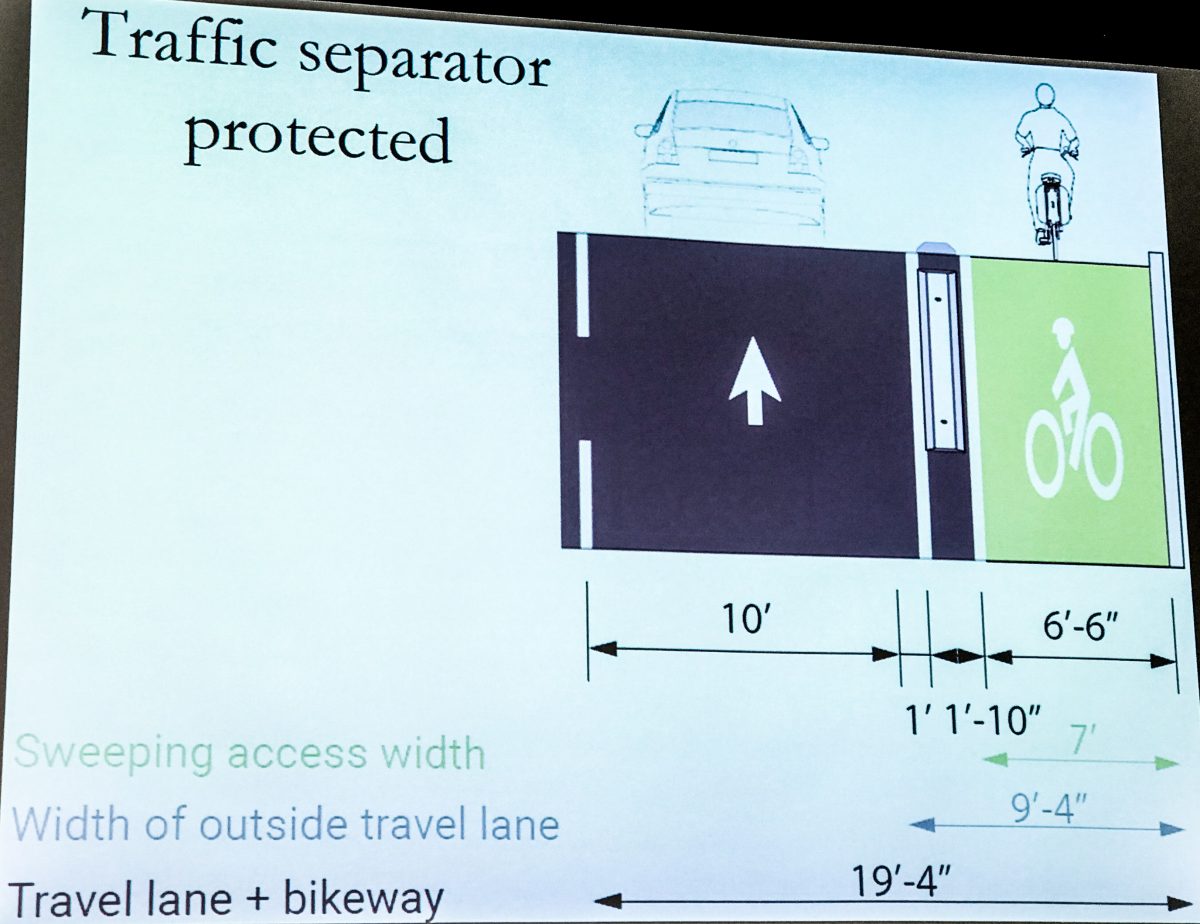

Let’s say PBOT plans to redesign a 36-foot wide roadway like NW Thurman, which today has two vehicle lanes and two lanes used for parking cars. Project staff could turn to this new design guide and see how to layout the street with six-and-a-half foot bike lanes protected from motor vehicle traffic with a one-and-a-half foot buffer zone that could be filled with a cement curb or plastic delineator wands.

Those wands are all too familiar to many Portlanders. They are often damaged, driven over, and knocked down by drivers. So much so they’ve tarnished the name of protected bike lanes. Geller fells our pain. He acknowledged on Thursday that the wands aren’t working as well as he’d hoped. “If you would ask me a year ago what Portland was going to look like with protected bikeways, I would have said we were going to become a city of delineator-post protected bikeways,” he said. “But based on the experience we’ve had with them, I think we’re going to have a more nuanced approach.” Citing exorbitant maintenance costs, Geller said PBOT is still learning what type of locations they work well in, and where other options might work better.

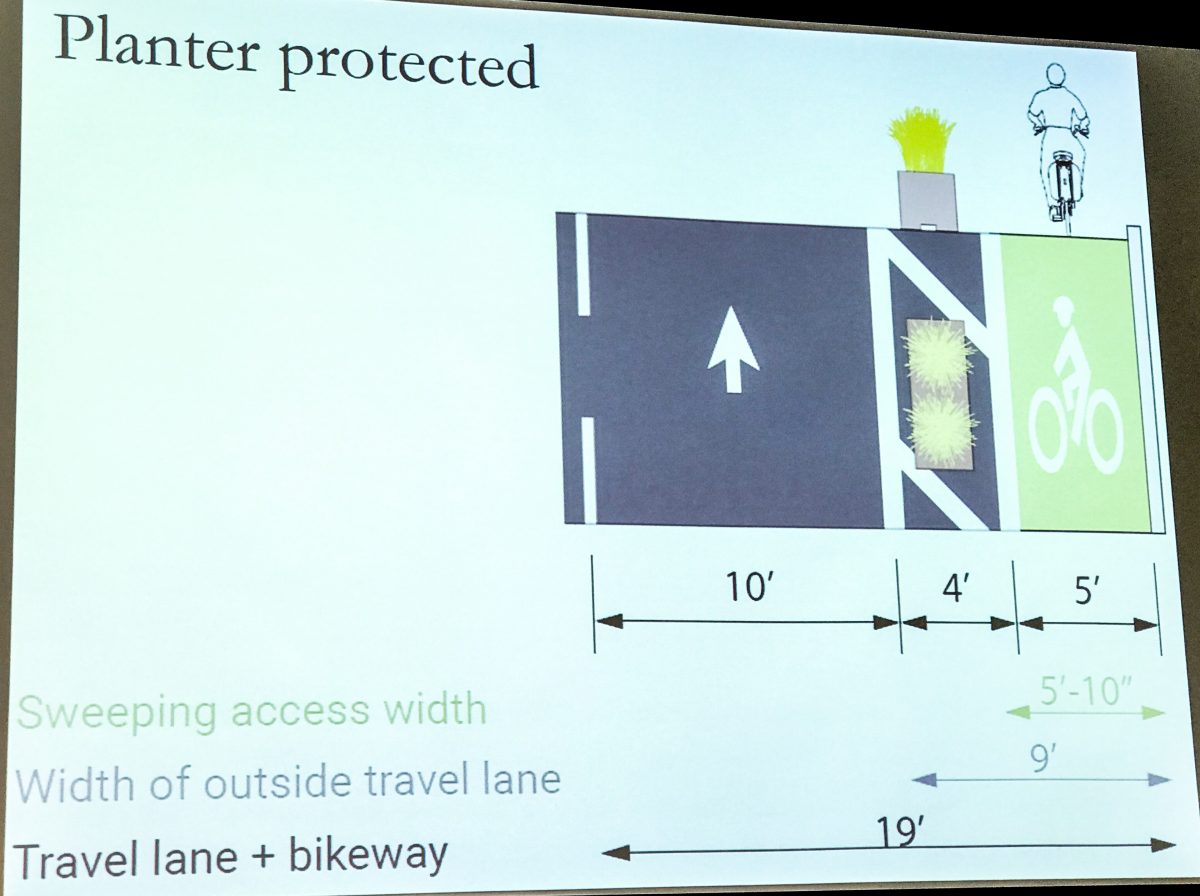

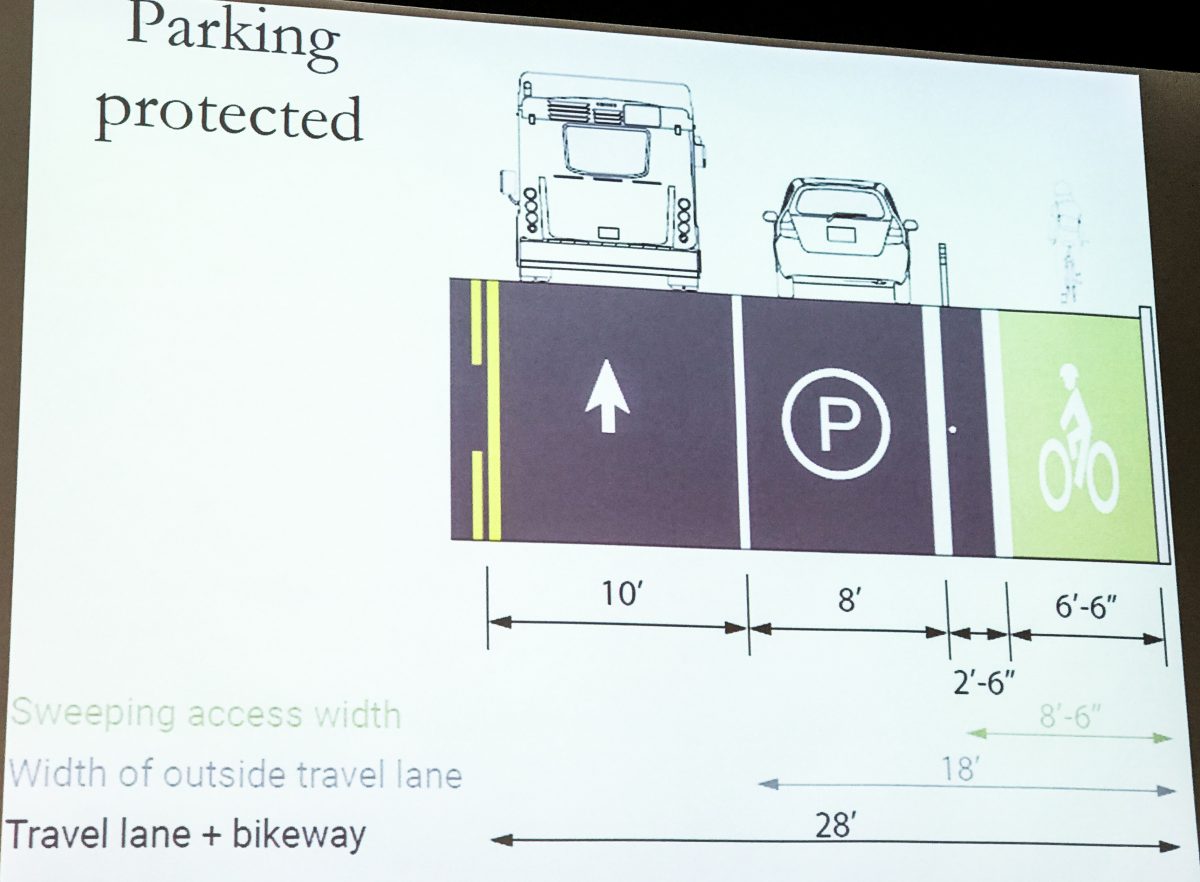

Another maintenance issue is whether or not sweepers can access protected bike lanes. The guide includes “sweeping access width” measurements for all the designs so maintenance staff will know which sweeper is needed for the job.

Advertisement

Where designs beyond plastic posts make sense, this new guide will help PBOT determine what to use. It includes guidance on other materials that can be used for protection: traffic separators (curbs), concrete islands, planters, or parked cars.

(Click images for gallery. ESC to return to post.)

Of course these other options are more expensive than delineator posts, and therein lies the rub. Geller said traffic separator curbs are four times the costs of the posts, “Which can be a stretch for us.”

(Photo: PBOT/Roger Geller)

For projects with a larger budget, the guide also lays out PBOT’s preferred design: a bikeway separated from other traffic and elevated to the same level as the sidewalk. Geller said that design — which requires 21-feet of width to fit an eight-foot sidewalk, seven-foot bike lane and six-feet of buffer space — is preferred because of its flexibility and the sense of protection it provides.

While there aren’t many opportunities for PBOT to build their dream design (the guide focuses primarily on retrofits, not new construction), Geller said they’ve also done a mapping process to identify roads with potential for protected bike lane treatments. He said, “We’ve got about 450 miles of roadways we’re identifying for these kind of treatments.”

As for how much these retrofits would cost, it depends on the design. On the low-end, PBOT estimates a basic, parking protected bike lane on a one-way road would cost $70,000 per mile. On the high-end, if they were to convert a road with five standard vehicle lanes to three and add protected bike lanes separated by a concrete island it would cost them $2.8 million per mile.

One thing you won’t find in the guide is the issue of how to address intersections. Geller said that’s because those solutions are constantly evolving. As PBOT continues to do their own research and analysis, they rely on existing manuals from other agencies and organizations that have already established best practices.

When it came time to answer questions from the audience, several people (including myself) wanted to know if having this guide in hand would lead to faster implementation. “I think this will facilitate faster implementation,” Geller said. With PBOT engineers now working from a standard set of drawings, it will be easier for them to decide what to do. But the limiting factor isn’t engineering, it’s money. “The thing that will hasten them is funding,” Geller added (and then pointed out how PBOT already has money for miles of protected bike lanes on deck for the Central City in Motion project and projects coming on North Rosa Parks, Denver, Greeley and elsewhere).

Also worth noting is that many streets that already have painted buffers will now be even stronger candidates for some sort of physical protection.

Overall, having this guide should significantly improve Portland’s ability to install protected bike lanes. While it gives PBOT a helpful tool, Geller said he hopes we, “Don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good.”

“We recognize we’re going to fail at times,” he said. “We’re not always going to be able to get our ideal design; but at least we know what we’re striving to achieve.”

The new guide is expected to be adopted by City Council by the end of June. I’ll post a public version once it’s released.

— Jonathan Maus: (503) 706-8804, @jonathan_maus on Twitter and jonathan@bikeportland.org

Never miss a story. Sign-up for the daily BP Headlines email.

BikePortland needs your support.