A few miles up the road, Portland’s big-sister city is doing something Portland hasn’t yet: charting a viable path to paying for its transportation goals.

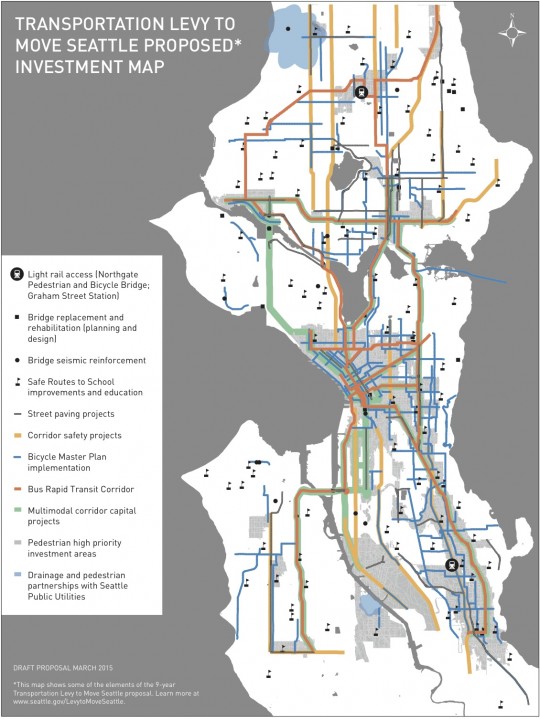

The nine-year, $900 million “Move Seattle” property tax levy proposed Wednesday by Mayor Ed Murray would include (among many other things) 50 miles of protected bike lanes and 60 miles of neighborhood greenways over nine years. That’s about half of the projects that Seattle’s 20-year bike plan refers to as parts of the “citywide network.”

For comparison’s sake, Portland’s “paused” street fund proposal included, at one point, an estimated 14-20 miles of protected bike lanes and 40-50 miles of greenways over 10 years. But the possible lessons here for Portland aren’t just about scale (Seattle is bigger by most measures, after all) and the story here isn’t just that Seattle is succeeding where we aren’t (Seattle has a long way to go, after all).

As we all wait, somewhat confused, to see when Portland City Council will again decide to take up this problem (Transportation Commissioner Steve Novick says he plans to take it back up after the Legislature adjourns), here are some notes about Seattle’s proposal that Portlanders might find useful.

It’s going straight to voters. Despite calisthenic attempts to keep their street fund proposal off the ballot, Portland Mayor Charlie Hales and Transportation Commissioner Steve Novick couldn’t find a city council majority that could do so. By framing the issue from the get-go as a choice for voters, Murray is greatly simplifying his messaging around a public vote that probably would have been inevitable anyway.

It’s a big risk. This isn’t likely to be an easy sell. Murray is asking voters to more than double their expiring transportation property tax levy, from $130 a year to $275 a year for the median home.

The virtue of this is that it gives voters a chance to make a big decision with big payoff. Seattle Transportation Director Scott Kubly has been noting, correctly, that both of those cost figures are dwarfed by the thousands of dollars each year that the median Seattle resident has to spend on car transportation. Small investments in transit and biking benefit mostly the people who already use those modes. Big investments benefit everyone, because they actually reduce car use.

Advertisement

Seattle is framing biking and transit as benefits to everyone. Politically speaking, there are two ways to see bicycle transportation improvements: as a tool for appeasing a tiny interest group of bike advocates, or as a tool for preventing a city from drowning in its own congestion. Murray’s administration is being very clear that it sees bikes as the second thing. From Wednesday’s coverage in The Stranger:

The future of this city is not in cars. As SDOT director Scott Kubly pointed out multiple times today, if all the people moving to our city—60,000 new people by 2025, according to the mayor—have to drive their cars everywhere, we’ll descend into an awful hellscape of traffic jams even worse than what we have now.

Portland politicians seem to have lost track of this narrative. Which is odd, since Portland is maybe the best evidence in the country that this works.

(Photo: J.Maus/BikePortland)

It’s a boring old property tax. Why has 87.4 percent of Portland’s public conversation been about the street fund about how the money would be collected rather than all the neat stuff it would buy? Because Portland was trying to create a new sort of tax. By using an existing tax, Murray is starting the conversation with the benefits rather than the costs.

The main problem here is that Oregon’s property tax system, unlike Washington’s, is both conversation-killingly unfair and designed to pit ballot issues against each other before they even get in front of voters. Property taxes aren’t perfect, but they’re simple, broad-based and (under Washington’s constitution) relatively progressive. Novick has yet to float a Street Fund proposal that hits all three of those marks.

It’s a compromise. When it comes to transportation ballot issues, the conventional wisdom seems to be that unless local business advocacy groups are on board (and therefore, usually, the local newspaper’s editorial board), no one will be shouting “yes” loud enough to persuade voters to raise their taxes.

It’s not yet clear whether Murray got a sign-off from the Downtown Seattle Association or Greater Seattle Chamber of Commerce, though Cascade Policy Club Policy Manager Brock Howell said Wednesday that he didn’t expect either group to oppose it — adding that the plan falls well short of advocates’ stated goals for 250 miles of new bikeways by 2024. With Seattle City Council yet to act on Murray’s proposal, the compromises up north are sure to keep coming.

But if Seattle business and biking advocates end up teaming up to support this issue, it won’t be mostly because they’ve each secured an appropriate share of goodies. It’ll be mostly because business advocates in Seattle see bikes and transit as ways to increase the capacity of the road system. Until Portland can once again see transportation investments that way, compromises are likely to remain something biking advocates can only dream of.