(Click to enlarge, or click here to play the spreadsheet-based game.)

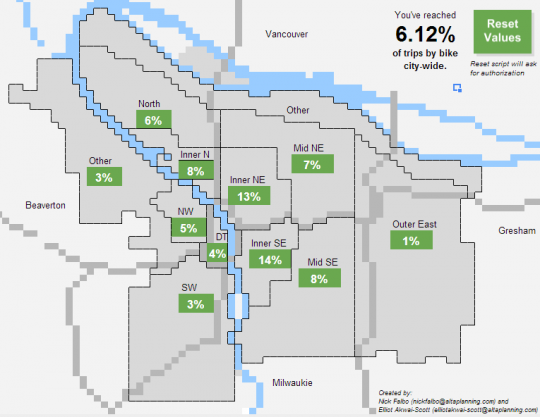

The City of Portland’s official goal for 16 years from today is for one in four commutes to happen by bicycle, up from 6 percent today.

As many people have observed, that’s a tall order. But an ingenious new web game from two local planning pros lets you put your own hand to it.

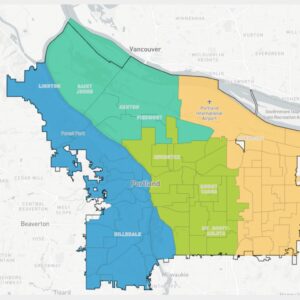

Nick Falbo and Elliot Akwai-Scott, both of Alta Planning and Design, have created a Google spreadsheet with cells shaded and merged into a map of Portland. The current bike commute rate in each part of the city is labeled, and behind the scenes the sheet is tracking the population of each part of the city, too. When you adjust the commuting rate in a certain neighborhood — from 6.3 percent in North Portland to, say, 30 percent — you can see how the citywide total changes, too.

Because the game is based entirely in Google Docs, it doesn’t display well on phones or tablets. But if you have a Google account, it works like a charm in a desktop browser.

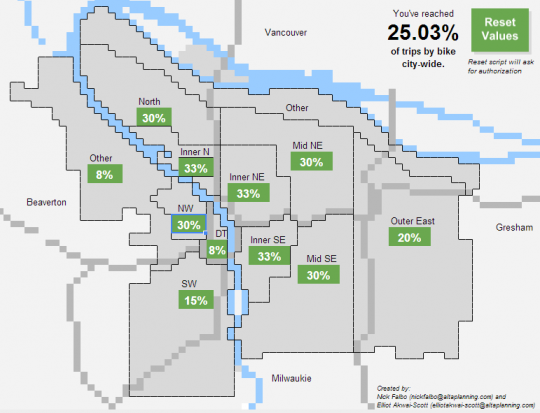

I tried a few ways to solve the puzzle. Here’s one way that takes a rough stab at what Portland bike coordinator Roger Geller says is most likely to work (PDF): substantially improving bike infrastructure everywhere, but focusing the heaviest investments in the central neighborhoods that were originally designed for streetcars, bikes and buggies rather than for cars.

The problem is that because the population of East and Southwest Portland is so huge (70,000 Portlanders live east of I-205), you need extraordinarily high bike-commute rates in the central city — almost as high as the bike-friendliest Dutch cities — to get to 25 percent.

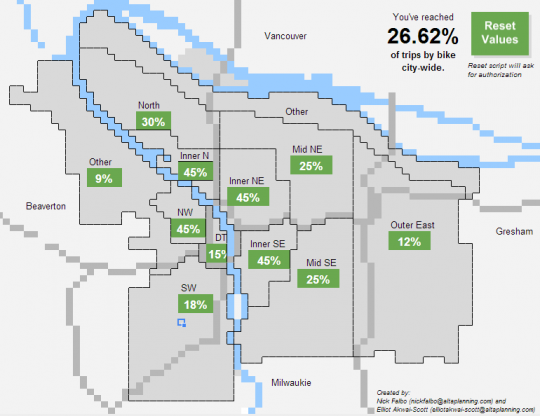

Here’s a different scenario, in which we manage to distribute biking rates more evenly around the city:

The challenge in this scenario is thinking about how much work it’d take to boost East Portland’s bike commuting rate to almost twice the current rate in inner Southeast. It’s not just a question of proximity to jobs, after all: a big reason bike commuting into downtown is so popular is that downtown Portland charges for car parking. Even if Gateway became a major employment hub, it wouldn’t draw many bike commuters unless its businesses stopped giving parking spaces away for free.

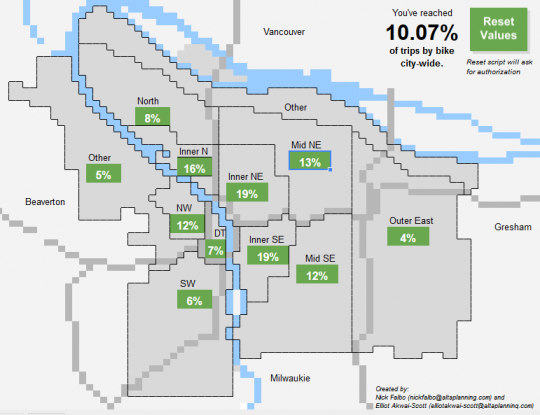

Before publishing this post, I had one more idea I wanted to test: what if the bike-friendly parts of town got much more dense? How much difference would that make to the bike commuting?

So I looked up the city’s projections for future growth by quadrant, entered those into Falbo and Akwai-Scott’s behind-the-scenes spreadsheet, added 10,000 more people to every central area for good measure, and used my original scenario for biking rates by neighborhood.

It helped. But as you can see in the upper right, not a lot:

In an email to the Active Right of Way listserv, sharing this project, Falbo asked: “What’s the best way to 25%? Is is realistic to even think we can reach a mode share that high?”

This project makes it clear just how ambitious the city’s stated goals are. But it’s also a great way to get a sense for what is possible, and what it’d take to get there.

Update 4:50 pm: Commenter Allan R. suggests setting a different, shorter-term goal. How about 10 percent by, say, 2020? Former Portland Transportation Commissioner Tom Miller said in 2012 that the city was planning an interim target. Here’s what that might look like:

I wonder if it would be better to have a shorter term goal like 10-15% and try to hit it before going all the way. This game felt discouraging when I clicked through it

Great point, Allan. I just added such a scenario to this post.

Assuming an employment center at Gateway that is comparable to downtown, I came up with the following:

Other – 5%, there are terrain and development issues in this area

Downtown – 5%, bikes really aren’t the most intuitive/human energy conserving mode unless you’re crossing the entire downtown district. I’m guessing that walking/transit will continue to prevail here.

SW – 10%, considering the terrain, without a dedicated (expensive) trail system to downtown I don’t see this area making huge gains.

NW – 15% if the employment mix at Montgomery park becomes a little more localized

North – 25% , assuming more employment in the Williams corridor and better crossing over I-5 and more folks that work in NW choosing St Johns

Inner N/ NE/SE – 30%, essentially doubling mode share to Downtown and the Central Eastside

Mid NE/SE – Assuming more employment in East Portland centers (Gateway, JCID, Columbia Corridor) giving folks double opportunity. This could be an area where two income households who have jobs in opposite directions could live and both choose to bike commute.

Outer East – 30%, I think this could easily be accomplished by focusing on connectivity from existing facilities and retrofitting wide streets (re -striping is relatively cheap). The heavy lift is the employment center development. I don’t agree about the parking. As land value changes, private lots will be redeveloped – at least partially, and retail lots don’t facilitate all-day parking. There’s a lot of opportunity for pricing parking along Halsey/Weidler and also along streets like Pacific, 99th and 102nd. I know it’s anecdotal, but I’m switching to bike commuting because I live in East Portland and my job is moving to Gateway in July. And, part of that is there’s a bike freeway from my house to my new office – the I 205 MUP.

Do you think the bike mode share in Outer East is currently so low because of 1) less infrastructure (fewer bike lanes), 2) distance from workplace (any data on where Outer East residents work?), 3) demographics (a broad term), 4) self-selection (maybe people choose to pay the costs of living close-in partly because they want to drive less, people choose to live far out partly because they are indifferent to all the driving – among other factors of course), 5) other?

My guess is that central city dwellers think it’s 4,1,3,2 in that order.

My assessment is –

1 – Distance to employment centers.

2- Missing infrastructure connections and uninspiring infrastructure. Where there are bike lanes on larger streets, they’re narrow and look like a compromise/afterthought. Where there are greenways or trails, the crossings of and connections onto the large streets aren’t comfortable/well worked out (Division at 85th is good, the MUP crossings are good but the connections are not).

3- Lack of bike lanes on obvious streets like Glisan.

4- Lack of support amenities like bike parking

5- Professional offices are small, isolated and scattered where they exist, and lack amenities like showers and secure parking. Industrial employment centers are either underdeveloped where they have good bike access (Freeway Land Co, Johonson Creek Industrial Area) or have poor bike access where there are large employment parks (Columbia Corridor, Gresham)

6- Access to bike shops/lack of bike maintenance and repair options and other support ammenities

I’d add a seventh: maintenance. The small bike lanes in East Portland are often full of glass, rocks, and other debris that make them extra unpleasant to ride in.

I agree. East Portland hasn’t had as much bike/walk outreach from the public agencies or the advocacy organizations over the years. So, the “call 823-SAFE” message isn’t part of the normal reaction to stuff like that. People just assume the lack of cleaning/maintenance is the norm.

I was looking at commute distance data in the tool referred to by RJ below. East Portlander residents appear to have jobs scattered widely across the city (longer biking distance), versus residents of close-in neighborhoods who appear to have jobs more concentrated in the downtown core (shorter biking distance).

Yep, we work downtown, in Clackamas County, in Vancouver, in Tualatin, in Hillsboro, all over Portland etc. That doesn’t mean we wouldn’t be happy to work closer to home.

Actually – part of the reason my employer chose to move to Gateway is that we analyzed the location of our partner businesses, and where our employees lived and Gateway was one of the three locations that made sense. In the three years that we’ve spent finding the real estate, financing the project and building the office, we’ve hire more employees that live in East Portland, and more of our existing employees have moved to East Portland. It’s affordable and that’s the biggest draw.

Oops – missed the percentage on the Mids – should be 30%

I played with it for a few, but mostly it became clear that it ain’t going to happen without massive development on the mid and outer east side/North side. Simply because this is where most the people live.

And since Downtown only accounts for roughly 25% of the employment of the city, you’ll never come close if focus is set on Downtown and the low populations of inner east side and (sorry folks) west side.

Focusing on the middle east side (yes I’m partial since I live in that area) would connect jobs and housing which are in the outer rings and inner rings. Which would increase bike share in all of the east side. Since people that live inner but work outer (or the other way around) might bike more often, and at the same time increasing options for those in the middle as well.

Though i got to admit, rather than going for 25%, I was looking more at smaller effects in specific regions. Like if the rest of the city stayed the same but outer east got to 5%, we’d be near the 7% mark. Jump it 10% and your at the 8% mark with the rest of the city still untouched. OR NW hills, NW and Downtown at 100% (with the rest of the city untouched) would only get you 15.65%, Though if SW went 100% too, then you’ve hit over the 25% mark.

We always talk about trends in future bike mode share from a demand perspective: how can we increase demand for biking? What infrastructure changes can we envision, build that will yield this result?

But what if we have this backwards?

Here’s a quote from a related discussion:

“…historically everyone has modeled future oil supply from a demand perspective. That’s what the IEA does, that’s what everyone does. You know they just forecast demand and they say, ‘well there will be supply and it will be at an acceptable price.’ And that’s fine while you are looking at over a century of continually growing oil supply that’s relatively cheap. But that’s not the case anymore. We’ve exited that era in history. We’ve gotten into a supply constrained world.”

I think we conceptualize how to increase biking in Portland a bit like this. But I don’t think it is going to work out this way. I think the supply of what we now think of as the default transport mode–the horseless carriage–is going to go poof. Probably not all at once, but faster than many of us probably imagine. Automobility drying up and blowing away is going to be a much bigger, and probably faster, driver of growing bike mode share. At least that is how I see it.

Though I agree that we’re past peek oil (fracking, deep water drilling and artic drilling is all the proof you need). The automobile isn’t going anywhere.

There are other ways to power an automobile, bio fuels and electricity- not to mention natural gas and propane.

Worse case America will start going back to making nuclear power to supply the power to run it’s fleet.

The real problem for society with oil supply running out is going to be the loss of plastic and other little things made from oil which you don’t ever really think about or know about (start stocking up on tires and tubes….).

Oil running out isn’t the half of it. Climate change requires that we leave those other related goodies in the ground, not dig them up and burn them in cars or power plants. I know our electeds haven’t shown much awareness of this, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t staring us in the face.

Biofuels are a disaster on a scale that is comparable to fossil fuels once we’ve burned through the waste feedstocks from agriculture (and maybe forestry) which in any case wouldn’t power but a few % of our current fleet/VMT/level of expectation when it comes to driving.

I agree with you that those who stand to make money/stay in power will do everything they can to deny this, try to find workarounds, spend our tax dollars to kill those people in other countries who happen to be living atop our fossil fuels, but none of this will change the inexorable logic of climate change.

Yes, climate change would require that we do that. But that does not automatically mean the death of the personal automobile as many would hope.

Even assuming that Americans finally take GCC seriously and a significant share abandon their cars — and many of our cities become much less car-dependent — I won’t be surprised if the remaining drivers end up demanding that a bunch of nuke plants be built to hydrolyze water for their cars. If the fuel cell cars aren’t ready in quantity at that time, hydrogen piston engines cost about the same to make as diesel engines.

My apologies to Howard Kunstler.

Oops, meant James Howard Kunstler.

You write about two terms: commute mode share and total mode share. Are those comparable in countries like the netherlands? Are there examples were people commute by train, bus, even car, but for getting to school, grocery store, coffee shop, movies and whatnot they bike?

This article shows how hard it is to reach those high, round numbers.

I would like to see a graph of bike mode share in Portland over the last 20 years and then show projections to 2030. My guess is that to reach a goal of 25%, or 20% or even 15%, the trend would have to change quite radically.

“My guess is that to reach a goal of 25%, or 20% or even 15%, the trend would have to change quite radically.”

Mathematically speaking that is the only way this can happen. A discontinuity. Coincidentally(?) we find ourselves in the midst of the biggest discontinuity our planet has seen in ~800,000 years:

“The only real surprises have been that some changes, such as sea level rise and Arctic sea ice decline, have outpaced earlier projections.”

http://nca2014.globalchange.gov/highlights/overview/overview

Commutes are only 1/4 of all trips, but 1/3 of all miles. If you were to ask me to pick 25% of trips to try to convert to bicycle, I’d look at all-trips that were 2.5 miles or less (also 25%), instead of all-commutes.

Here, I’ll flog my blog, I don’t care, it’s got the numbers graphed, references, etc: http://dr2chase.wordpress.com/2014/04/09/short-trips-in-cars/

Check out the paper Michael linked to in the article: https://www.portlandoregon.gov/transportation/article/452524

To reach 25% mode split (all trips) bicycling would have to grow 1.4 times faster between 2011-2035 than it did 1994-2011. Also see the graphs on page A-6 that show the necessary growth curves to achieve both 25% and the lower 15% goal over that time period. The graphs shows that other cities have achieved the needed fast growth curves at high mode split levels. In other words: it can be done.

You can also see these graphs animated in a presentation based on this paper at the Portland Transportation website: ftp://ftp02.portlandoregon.gov/PBOT/BikeBrownBag/2013.03.21_BikeBrownBag_PathAheadForAT_Geller_slides.pdf

The paper also discusses how different parts of the city need to grow bicycle use and how they might achieve that (see Appendix A).

cycling mode share in portland has been stagnant for ~5 years and hawthorne bridge count numbers suggest another year of stagnation.

a common denominator of nations with high cycling mode share is that they have policies that actively discourage driving. imo, there is zero interest in actively discouraging driving in portland city government. i also believe that city policies which encouraged gentrification and development that caters to the top quintile is helping discourage public and active transport growth.

waiting for the next recession and/or spike in gas prices to boost active transport mode share is not a plan.

“there is zero interest in actively discouraging driving in portland city government”

I know. What happened?

European urban centers are almost 3 times more dense than those in the USA. We will never reach 25% mode share if we don’t encourage density (e.g. build up) and discourage sprawl.

http://www.demographia.com/db-intlua-area2000.htm

http://projects.oregonlive.com/maps/density/

Most EU cities I’ve been to aren’t built all that much upwards. The problem with density in US cities isn’t that we don’t build up, it’s that when we build up we still require 2000+ sq ft of living space so end up with 20, 30 40 story buildings to get the same density as EU. Density doesn’t require high rises creating concrete canyons like NYC. Much as we need a road diet, we really need an apartment diet.

This!

I think 2 things need to become more prevalent in order to reach these kinds of density targets: “apodment” style units and larger family units.

These are essentially the same thing, with the apodments being more biased to rent to multiple renters, and the larger family units being biased to rent to fewer renters or just families.

The ratio of bedrooms to everything else really needs to increase. The ‘large’ apartments in new buildings tend to be 2 bed 2 bath 1 living/ kitchen. Sometimes they also have a laundry closet. But then inside the building you’re repeating over and over all these bathrooms and kitchen appliances and laundry machines that really could probably be used by more than 2 people. The great thing about apodments is that by having 4-5 bedrooms and maybe 2 baths per 1living/kitchen/laundry, the building as a whole can have higher density, and each of the renters can usually save quite a bit of money.

I’m always baffled by NIMBY protestations against these kinds of units as inhumanely crowded. This is usually a smokescreen for fears about change/parking/people of different social class, but still. You know that if people can’t find affordable 5 bedroom rental apartments (with great lease rules and bedroom locks built int), they’ll just find a 5 bedroom house, right?

-Where are the jobs for the folks who sign-up to live in the overpriced pods? If they’re in the suburbs, infilling does not correct transportation issues.

-We need to stop infilling the city until we address the mess that lies on the otherside of 82.

-NIMBY is a legit concern. Developers should not be allowed to build whatever they’d like on the back of bike culture and trendy neighborhoods. These home and business owners, want answers beyond, “oh, everyone will ride a bike”.

-We don’t need more bedrooms. We need more neighborhood structure (grocers, parks, etc) and employers in outer NE/SE/N. With the revitalization of neighborhoods like Cully and FOPO there’s a migration of renters who are slowly encroaching on the 82 barrier to buy homes. Supply and demand will likely dictate the re-re”gentrification”. But that’s not entirely fair to the families already deserving of inner Portland amenities.

-If we truly need pods, I suggest we reconsider the high rise mega apartments we’re building on already vacant land sitting on the river. Or we consider opportunities to remove apartments built in the 70s and rebuild to smaller units. N Portland is perfect for this, thought it’s not nearly trendy enough for the developers to jump on (yet).

-Infilling inside of 82 doesn’t correct the larger trends of suburbia and major employers not wanting to be located inside the city limits. Nike, Intel, and Columbia for example.

-Take Swan Island and the Terminals off Marine Drive as a case study: Where are the (well over 10,000) employees of these “districts” commuting to and from? Do they want to live off Division? Does it makes since for them to live off Division? Where does it makes sense to infill?

This is kind of a second question. The fact of the matter is there ARE a lot of small to medium size developments going up ‘inside 82nd’ as you put it. I’m talking about the *form* of those developments.

I feel like there are probably plenty of renters in older units onfurther out in E or N Portland that would be willing to switch to these kinds of units if they were closer to their actual place of employment or school *and offered at similar rent per bedroom*. If you’re currently paying 450/mo to live in a 2br 1ba with 1 roommate, you can’t move closer in into new developments charging 1000/mo for a 1br or 1400/mo for 2br. But maybe you would be able to move into a large 5br 2ba unit charging 2500/mo. If people are already riding the bus down division everyday sitting in traffic for an hour, why wouldn’t they want to change that to sotting on the bus for 30min?

I also feel like there are many young families and families with 1-2 children that would appreciate being able to live closer in (for the same reasons) without having to give an arm and a leg for a house in these gentrifying neighborhoods. There are some older condos in my neighborhood for example that are popular with retirees and young families, but the quantity is less than the demand.

The current standards of design produces very expensive rental stock that meets the needs of a portion of potential renters. I’m talking about broadening that so that renting in close in areas is more accessible to more kinds of people.

Besides, who says this can only happen inside Portland? These kinds of developments should be going up anywhere that claims it is trying to do TOD. Gresham, downtown Beaverton, downtown Milkwalkee. etc.

Hi B-

I agree. We’re largely on the same page, aside from maybe 75 sq ft.

I believe it is currently too easy for developers to build. Almost feels as if the city isn’t managing density.

“Or we consider opportunities to remove apartments built in the 70s and rebuild to smaller units.”

The zoning laws that nimby inner pdxers vehmently defend prevent this. Many of the beige/olive 60s/70s era small apartment buildings in inner PDX are in areas where development of small apartment buildings is not allowed.

When it comes to zoning laws PDX is the OC of Cascadia.

i agree that we need to learn to accept smaller homes, however, NYC has by far the lowest per capita GHG emissions per capita in the usa. moreover, the literature on urban GHG emissions argues strongly for building up:

http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTUWM/Resources/GHG_Index_Mar_9_2011.pdf

http://eau.sagepub.com/content/23/1/207.full.pdf+html

http://eau.sagepub.com/content/21/1/185.full.pdf+html

Density requires neither 20+ story high rises, nor does it require us all to live in tiny apartments with 100-200sf per person. Not that there’s anything wrong with the existence of tiny apartments, but they don’t all (or even mostly) need to be that small.

Even if we just went to lots of mid-rise (4-6 story) buildings with 300-400sf/person – including plenty of 2-4BR units for families – we would get there.

Agreed. These guys are talking about “density” as if it were from another planet, not just another country, or (the horror!) some other part of the United States. Have a look at Somerville, MA. Not quite triple the density of Groningen. Over twice the density of Amsterdam. Not many tall buildings, lots of 2 and 3 families, and not much wasted space.

8000 per square mile is easy. We have “suburbs” here that are that dense.

Cool Google doc. What would be REALLY cool is if you could gamifiy it a step further, and change the mode splits by implementing different policies like “build shiny new cycletracks everywhere,” “implement dynamic/market rate parking pricing,” “prohibit people from intimidating the interested/concerned by wearing grimy yellow showers pass gear and/or knickers.”

The way 25% by 2035 is going to happen, IMHO, is not by convincing the next 19% of today’s “interested but concerned” to take up biking. It’s going to happen by generational change (children growing up in Portland out-millenial the millenials by adopting the car-lite/car-free living even more strongly than their parents), and by in-migration and added density in bikeable areas (people who want to live car-lite/car-free keep moving to Portland from bike-unfriendly cities).

If you really want to wonk out on commute patterns (i.e., census journey-to-work data), try this:

http://onthemap.ces.census.gov/

Thank you!

Here’s how…

$12/gallon gasoline and Americans giving up laziness and comfort en masse for the greater good.

Any guesses as to which one will happen and which one will not?

I hear you. As Elizabeth Farrelly put it in a piece linked in this week’s Monday Roundup:

“But this isn’t about what I want. Sadly, it’s not even about what you want. It’s about the wants of the other 7.2 billion planetary humans. Which makes it, simply, obvious. We can’t all drive everywhere.”

Although we here in the US are used to getting our way, doing whatever we wish on the world stage, this too is probably not long for this world. I’d add to the quote above that it isn’t even, primarily, about what the other planetary humans want but about what will still be possible under less favorable and worsening climatic conditions.

Driving to the grocery store right now enjoys broad cultural support. When I bike and someone I know is driving to the same location we all recognize the transportation hierarchy when the person in the car offers me a ride (rather than the other way around, for instance). Many people operate according to what their peers deem acceptable or normal or desirable behavior. At some point the act of discretionary driving will cease to fit those descriptions.

1) Build world-class bike facilities that take you (and your grandmother, and your 10-year old) quickly, safely, and comfortably, the ENTIRE way from your home to your destination. Make this the #1 priority.

2) Remove the car subsidies that encourage more driving: parking requirements, underpriced on-street automobile storage, etc.

3) Create easy and obvious connections between bicycling and transit

4) Create a dense, well-planned bike share system in the downtown and densely built-up areas.

5) Encourage a greater mix of uses throughout the city.

Instead of hoping to increase the outlying areas percentages many dozens of percent (with their inherent increased limitations of distance and worse infrastructure to begin with) I’d consider it a success to simply see certain areas increase the most. A success may not be the total percentage but the percentage change. North, Other and Outer East are much bigger hurdles. NE and SE need the biggest ramp up (pun?) in volumes the “bike grid” can handle, but have the most going for them to begin with. Mid NE/SE will come along about 5-6% behind the NE/SE simply because of similar geography I’d wager.

But I’d prioritize figuring out why some very similar regions have such major differences. (SW, NW, Downtown and inner N)

Let’s look at each area individually and ask why that area has challenges in their bike use.

NW is oddly low given its location and terrain, infrastructure.

SW likely splits commutes a lot more West than other areas, and has terrible infrastructure to downtown.

Inner N is changing, it will have a lot of specific issues and opportunities.

Downtown is extremely low. Why?? Do people just walk to work locally or use TriMet? Then increasing biking is unlikely to be significant but that is OK!

In regards to employers, though Nike and Intel aren’t downtown, they are perfect for light rail as a shared commute. OHSU is as well, plus a tram (and some good training hills for those that want them) This is a huge plus. So why aren’t folks biking to the Max??

Yes, it would be great if Beaverton and Portland’s outer most areas biked more. But the challenges there are tremendously different. Solutions also very different. The distances alone needed to cover activities of daily living are much greater. Put that challenge in a different bucket mentally and I think we can focus on where we can make the biggest impacts.

I disagree that outer NE and SE have “much bigger hurdles”. What they have is an aggregate of small, relatively inexpensive projects that get ignored because we’re spending so much staff time and energy on the inner neighborhoods.

The major trails infrastructure in outer east already exists. The little projects and “paint” improvements need to get done. And, the development community and employers need to be shown that there’s a political will to make good on our poly-centers plans.

Geography- outer east is flat flat flat. Saying there are geography issues in outer east and then making no mention of the exponentially more challenging terrain in SW and parts of NW shows typical bias (based on lack of experience/familiarity/ground truth) in this city.

Not topography. Simply the distances involved. I’ve biked it a lot, usually adding on Max trips. Getting around takes FOREVER.

It’s great folks want to address what they can in these larger distance areas, but I can see where it may entail a different approach and prioritizing those may have less yield.

There is a reason it’s 1%…

Conversely, there are many known and used routes in the “Challenging” NW, SW where the distances involved are not great but the infrastructure is basically Barber blvd/terwilliger…

I have no idea why NW is so low. Anyone have theories??

You can see that downtown/NW have very high walking rates here:

http://www.census.gov/censusexplorer/censusexplorer-commuting.html

The sweet spot for biking is 1-3 miles (thus the high rates in inner SE); less than a mile, walking is probably more attractive.

So just like outer PDX, why are we using total percent biking from an area where walking instead is preferred? Maybe the goal instead of increasing bikes to 25% is to increase all non-car trips by a certain percent?

The city-wide goals are 25% transit, 25% bike, 7.5% walk, 10% carpool, 2.5% telecommute. That leaves 30% drive-alone. It is acknowledged that different areas of the city will contribute differently to these overall goals — the central city will contribute disproportionately to the walk %, inner neighborhoods will contribute disproportionately to the bike %, and areas around high-frequency transit will contribute disproportionately to the transit %.

Distances involved is relative and can also show central city bias. Folks that are tourists in East Portland often have a hard time wrapping their heads around wanting to go anywhere in East Portland (the “bike lane to nowhere phenomena). They also have a hard time wrapping their heads around anyone wanting to locate a business or employment center there.

It’s not a commute trip, but it takes me 5 minutes to bike from my house to Fubonn. (I guess if I worked at Fubonn it’d be a commute trip, but I’m a not a cashier at this stage in my career). It’s easy, there’s only one weird spot crossing Powell and not enough bike parking at Fubonn. If I worked at the TriMet Powell Garage, I’d bike there. If I worked at the ECC, I’d bike there. When my job moves to Gateway, I’ll be biking there (2.1 miles, 15 minutes) and I’m living well south of Gateway.

If you build Gateway (and the other town and neighborhood centers) to it’s zoned and intended purpose, the distance issue is moot. There will be jobs in East Portland in centralized areas that have services. They will be accessible by pretty robust bicycle infrastructure. All we’d need to do is fill the gaps.

no one here wrote that density requires high rises.

that was in response to glowboy above.

quoting is working very erratically on bike portland.

@spare_wheel: my comment was in response to “meh”s comment that current apartment sizes would require 20-40 story high rises to reach EU levels of density. I don’t think it’s true that on the whole we need an apartment diet. Yes there are some 2000+sf units, and there always will be rich people who want them, but that’s true in the EU too.