The details of the Portland Bureau of Transportation’s plans to invest in downtown bicycle access are getting clearer. As we shared back in February, PBOT has applied for $6 million in regional flexible funding (administered by Metro) in order to improve the transportation network in the downtown core.

Much about the plan — like specific locations and facility-types — remains undecided; but PBOT’s grant application (published on Metro’s website) provides the most detail we’ve seen yet about the project.

According to PBOT, their Portland Central City Multi‐Modal Safety Improvements project will, “plan for and address safety and access issues resulting from competing demands on transportation infrastructure in Portland’s central city.” From the description it’s clear PBOT is approaching this project as much more than simply a “bike project.” To them this is about updating and redesigning the existing roadways to respond to current demands, facilitate future needs, and meet our adopted mode share goals. Here’s an excerpt from the description:

This project will result in a strategy that identifies a multi‐modal transportation network that complements adjacent land uses, preserves capacity for important uses, and accommodates and encourages the already significant active transportation use in the central city today. The project will then identify and fund priority investments in active transportation.

To make the case for this investment, PBOT has boiled their argument down to two main points: the need to build a system that can accommodate more bicycle traffic (such as 25% bike mode share by 2030), and the need to make those trips safer. (Statistical models and usage trends prove that as Portland’s population increases, a larger share of the trip burden must fall on non-automobile modes.)

Here’s another key excerpt:

Beyond accommodating growth and achieving modal targets, however, lies a more serious issue of safety on the corridors leading in to and out of Portland’s central city. Fourteen of the top twenty high crash intersections for bicycling (1999‐2008) are within the proposed project area, and account for 94 (74%) of the 127 reported crashes that occurred at those 20 top locations. Similarly, six of the top twenty high crash intersections for walking (1999‐2008) are within the proposed project area, and account for 44 (31%) of the 140 reported crashes that occurred at those 20 top locations.

If these safety issues aren’t addressed, PBOT writes, we’ll see “declining active transportation use in the central city.”

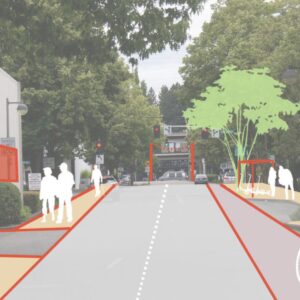

As for PBOT’s vision of what type of facilities they’ll build with this money, the application says they want to, “create as much separation between people walking or bicycling and automobile traffic.” And for PBOT, creating bikeways separated from auto traffic is, “both recognized and demonstrated to be a foundation for increasing non‐auto trips.”

PBOT describes the central city as the region’s top trip destination (as per Metro’s 2040 growth plan), a place where roads are used by many underserved communities, and a place with lackluster bicycle access. “Feeding into this background,” PBOT writes, “are the common complaints among Portland residents of how they feel “abandoned” by the city’s bikeway network once they access the Central City and how that creates a barrier to increased use.”

That feeling was summed up by a member of the City’s Bicycle Advisory Committee at their meeting earlier this month. Yonit Sharaby, a new mom who lives in northwest Portland, told a PBOT staffer and the committee members that when she takes friends on a bike ride they avoid downtown. “Portland is the city of bikes on the east side,” she said, “Portland is not the city of bikes on the west side.”

Hopefully this project — which PBOT says will be, “one of the most significant investments in active transportation this region has experienced in several years” — will change that once and for all.

— Metro is accepting public comments on this and 28 other projects from around the region until June 7th. See their website for more details.

“meet our adopted mode share goals”

finally. let’s do it.

Imagine what the $150 million spent on the Eastside streetcar could have done for everyone who drives, cycles, walks downtown and throughout our city.

I saw one go by today with no passengers.

Well… we could go down this path… and recall the $400 million that fooling around widening the freeway in the Rose Quarter is supposed to cost. I’d wager that (will be) money even less well spent when it comes to meeting our mode share goals.

Talk about ‘no passengers’ – freeways are one of the best places to see that every day.

I rarely bicycle downtown because of the poor air quality. Downtown PDX is sandwiched between two major freeways and diesel exhaust from each Trimet bus.

you breathe the same air in a car or bus (and you typically breathe it for longer).

I hear you. Riding down on Swan Island is no picnic either. Climbing the Going hill you are treated to a find blend of hot wind from trucks, brake dust, a diesel fumes.

“create as much separation between people walking or bicycling and automobile traffic.”

mode share has declined in denmark (more physical separation) and increased in germany (less physical separation).

“both recognized and demonstrated to be a foundation for increasing non‐auto trips.”

in the late 90s the dutch government spent ~$1 billion doubling the size of its physically separated paths and mode share only increased a few percent. on the other hand, there is plenty of evidence that traffic calming, traffic elimination, motorist usage taxes, and “in lane” infrastructure correlates well with increases in cycling mode share.

That line also gave me pause, but it could mean a few key streets closed to motor vehicles as well. I prefer minimal separation (traffic calming,bike lanes,sharrows, etc) in densely populated urban cores such as downtown over separated cycle tracks. Save the big money for the scariest places to ride.

1) the Dutch government is spending multi billions to build new freeways

2) downtown Portland is a vehicular bicyclist’s dream: virtually no separation, ‘share the lane’ with cars is really the only valid method of cycling as cycling on the sidewalk is illegal, and traffic lights are timed at 14mph.

Several problems with biking in downtown:

1) you get stuck in traffic along with cars – for most routes, cycling is not faster than driving unless you count time to find parking (bikes generally win)

2) bridge paths dump you unceremoniously into traffic without enough room to squeeze into high-moving traffic. Traffic normally is moving ~30-45 mph coming off the bridges.

3) safety – as stated above, very high risk for collisions

4) cycling is in decline in SW Portland

To address those concerns, it would make sense to start to dedicate car lanes to bike traffic, particularly since less than 50% of transportation occurs by car in downtown!

i agree. we should make significant swathes of downtown portland car-free or car-light. the creation of new auto-free and auto-light in the netherlands commenced in the 70s and correlated much better with increases in cycling mode share.

I’m curious about the actual increases/decreases and their correlation to infrastructure. Do you have some links that address this?

My initial reaction is mode share was already extremely high in Denmark and the Netherlands, and cycling could be expected to fluctuate based on a variety of factors, including bike congestion (a nice problem to have, but still a real problem, especially with bike parking, in Copenhagen and Amsterdam) and improvements in public transit.

Germany, on the other hand, had relatively low mode share to begin with (13% compared to Amsterdam’s 38% and Copenhagen’s 25%) and could be expected to increase at a faster clip with infrastructure improvements or cycling becoming more appealing in general. Berlin is big on shared sidewalks, shared bus lanes, cycle tracks of various degrees, and bicycle priority streets. I can’t find the source, but something like 60km out of an over 600 km network are in-street bike lanes. Is this hindering or helping ridership? I don’t know.

There needs to be an actual scientific study that proves statistically that cycling is in fact declining in Copenhagen, not just rumor based on a single bike counter that may or may not count all cyclists that travel past it.

Anyway, Copenhagen in general has far less separated bikeways than does Amsterdam, according to this article: “In contrast to most other case study cities, there are no bicycle streets in Copenhagen, and traffic calming is not very extensive.”

http://policy.rutgers.edu/faculty/pucher/Frontiers.pdf

Note that in 2005, in Amsterdam “cycling accounted for 37% of all vehicle trips.” (pg 8) By comparison, “20% of all trips in Copenhagen were by

bike.” (pg 26)

That all being said, I think that comparing Copenhagen or Denmark with anywhere in the US is just going to run into the apples vs oranges phenomenon. If anything, their bike numbers are incredibly good for Western cities and absolutely show what happens when you make proper investments into cycling, whether infrastructural, social/education, and happen to have a long, uninterrupted history with cycling.

However, Copenhagen in general has very narrow streets and a very high density. These factor in heavily, along with $10/gallon gas and non-free/limited parking throughout the city that are the opposite of what we have here in Portland.

Most interesting is Copenhagen’s budgetary approach to cycling: “Indeed, a third of Copenhagen’s road transport budget is earmarked for cycling

facilities and programs.”

-at least they are doing something right!

I would settle for a set of 6′ bike lanes criss-crossing downtown Portland, if only to let me get around traffic congestion in the city without getting stuck BEHIND cars. I like to bypass congestion – although intersections are a sticky issue, as always.

Edit – ok, gas prices have come down a bit, somewhere around $8/gallon in DK.

intersections are even stickier when you use physically separated infrastructure. there are cheap solutions to intersection conflict that largely involve inconveniencing motorists. imo, the more difficult and inconvenient we make motoring the better.

http://policy.rutgers.edu/faculty/pucher/irresistible.pdf

Fig. 7 shows a steady decline in cycling. It is also my understanding that recent numbers are worse, in part, triggered by a resurgence in road high way investment.

I fully support the purpose of this project, but why does the city consistently use the southern portion of I-405 as a boundary when some of the greatest challenges getting in/out of downtown lie on the I-405 bridges and their approaches? We’ve made significant improvements to bridge the gaps over the Willamette, but seem content to leave I-405 frozen in the 60’s as a huge pdestrian and bicycling barrier. A moat filled with cars.